Alamance County Community Remembrance Coalition member Loy Campbell said that it will be impossible to recover from the Jim Crow era of racial injustice if it's not talked about. Campbell said understanding how we got here is essential for finding a way to live in a society that is free from racial terror.

“It's not an effort to punish America or make people feel bad, but it's an effort to think about what we have done, and how can we move forward towards a place of true justice,” Campbell said.

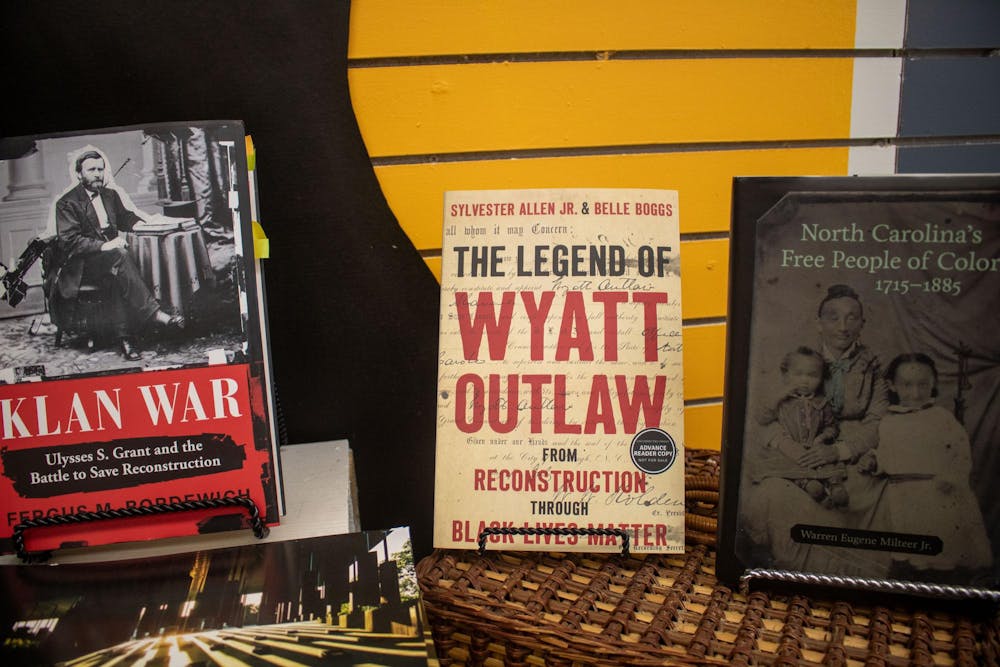

After almost 7 years of bringing stories of Alamance County’s past to light, the coalition has helped educate the community about three racial lynchings in the county’s past. Campbell said that the goal is to educate others about the lynchings of Wyatt Outlaw, William Puryear and John Jeffries. The coalition has many projects aimed at educating the community about the lynchings. One example is their soil collection project, where they collected soil from the site, or as close as they could get, of each lynching. The soil is preserved in the African-American Cultural Arts and History Center in Burlington.

Along with an annual vigil for Outlaw, the coalition is also beginning to work on a historical marker placement project, which would put up a marker for each lynching victim. Campbell said they will begin with the marker for Jefferies. Campbell also said that in the future, they want to claim a copy of Jeffries’s monument in the Equal Justice Initiative's memorial in Alabama. Campbell said they want to bring a copy back to place in Alamance County.

“The same threads of racism and white supremacy and violence and terror have been common throughout and they continue today,” Campbell said. “I think really understanding that narrative was a big part of why I thought it was important that we bring this history to life in Alamance County.”

Campbell said that seeing the museum was very powerful, especially with the current administration. Seeing humans being cruel to one another is something that Campbell said is disheartening.

“This past trip that I went on two weeks ago felt rebellious because right now we have a federal government that's trying to hide history and erase what has happened, and that's not gonna get us anywhere good,” Campbell said.

Wyatt Outlaw

Of the three documented lynchings in Alamance County, Outlaw’s death was the first to occur, and likely the most well-known, Campbell said. Outlaw was an important figure in the local community as he was the first African American to serve as Graham’s constable and town commissioner. Outlaw grew up enslaved but had significant freedom due to his white father, who was good friends with Outlaw’s slave owner, according to Carole Troxler, an 18th century historian who has worked with the coalition.

Outlaw was a representative at the Freedmen’s Convention in 1866 and became a significant figure in Alamance County’s history, organizing the Union League in the county. Troxler said that Outlaw met and allied with Republican governor William Woods Holden, who encouraged him to organize the league. In Graham, he owned a cabinet shop, which also served as a meeting place for the Union League and other Republican Party contacts. The Ku Klux Klan killed him for encouraging newly enfranchised black men to vote Republican, Troxler said. Outlaw was dragged out of his home during the night and was hanged from a tree near the courthouse in Graham.

Outlaw’s great-great-grandson, Samuel Merritt, said that he has learned more about Outlaw in the last five years than ever before. He said Outlaw was someone who embraced the well-being of people.

“He could have been a bandit. He could have been someone that murdered 15 people. But on the other side, he was not that,” Merritt said. “He was someone that stood for good, for goodness sake, he tried to do good. He tried to do a good job. He wasn't a hater of people.”

Merritt said he is grateful to see that Outlaw’s spirit lingers in the community.

“That spirit is still alive within the community, and people have recognized him, his works, his deeds, and the events that happened during his lifetime,” Merritt said. “I'm wowed by that because, like I said, this didn't happen when my mother or grandmother were still living.”

William Puryear

The next lynching in Alamance County was the killing of Puryear, a black man who was speaking out against the lynching of Outlaw. Shortly after Outlaw’s death, Puryear recognized one of the men who had captured Outlaw and reported this information to a Graham magistrate, according to Troxler. Puryear was then taken from his home by a mob, and his body was found a few weeks later in a mill pond with a 20-pound stone tied to his foot.

John Jeffries

The last recorded lynching was of Jeffries, who was killed in 1920. Campbell said that Jeffries didn’t actually live in Alamance County, but worked in the county. Jeffries, a resident of Granville County, got off the train at Elon to go to work. Jefferies was accused of raping a young girl. A mob, which was led by Elon College President William Harper, carried out the lynching. Elon University describes Harper’s role on their Anti-Black Racism From Elon’s History project. According to the website, part of the goal is to “examine Elon’s institutional history in a transparent, participatory and intellectually rigorous manner.”

Campbell said that the coalition is looking to create a historical marker to honor Jeffries. With help from the EJI, they are hoping to have a ceremony within the next year or two, along with the marker.

The future of the coalition

Campbell said a big focus for the coalition is getting the word out and having more people attend their events. She said it's an uncomfortable topic for people to listen to and talk about.

“When you start talking about racial violence and lynching, people are very, very uncomfortable, especially white people. But also it's a very challenging thing to talk about with people of color,” Campbell said. “This is their heritage and so everybody's a little bit uncomfortable. And so I think it can be hard to get people to to come to an event or to learn more, because it's really hard, but it's important.”

Merritt said it is vital for people to understand Alamance County and the nation’s past to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

“You need to know where you went wrong in order to try to do right,” Merritt said. “There were some misdeeds done at that point in our history, and we need to recognize those. Not everything is pretty, so we need to have the good and the bad as a part of the total picture.”

Fiona McAllister contributed to the reporting of this story.