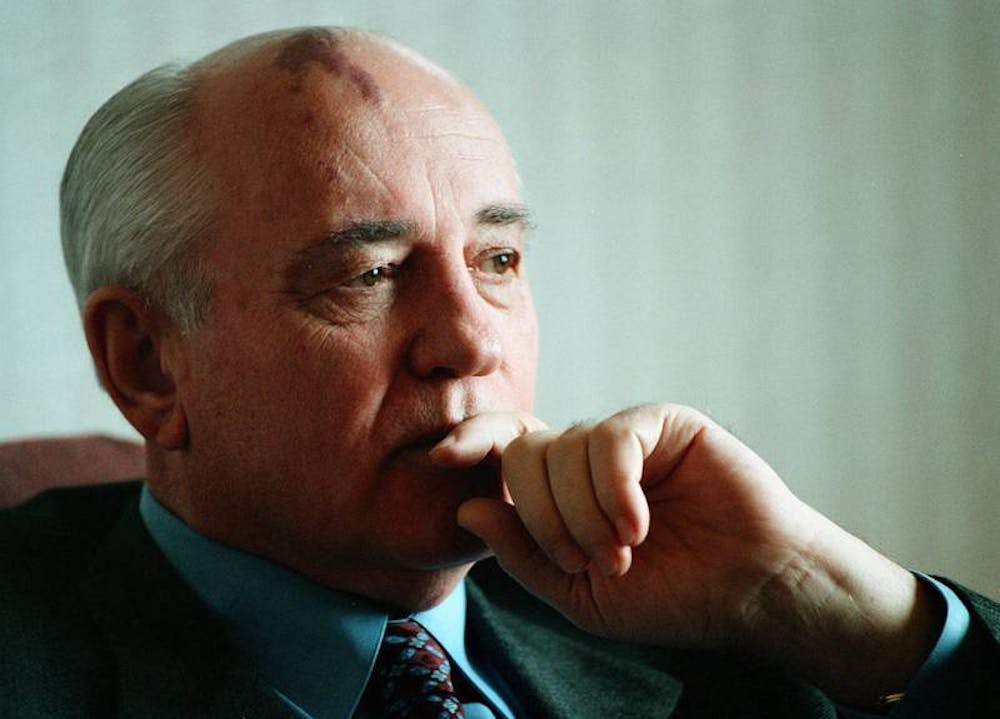

Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union and Nobel Peace Prize recipient, died Aug. 30 at the age of 91. Safia Swimelar, professor of political science and policy studies, explains Gorbachev’s efforts to democratize Russia’s political system, his role in the breakup of the Soviet Union and why Gorbachev’s legacy is crucial in understanding modern Russian and world politics, including the Russian-Ukrainian war.

This interview was edited for clarity.

How was Gorbachev a significant figure in world politics, specifically within Russia?

“To start from the beginning, he was most significant because he recognized, when he came to power in the mid ’80s, that the Soviet Union was not the great empire people had been believing in. If you looked at the economy, and you looked at the lack of freedoms that people had, then it was pretty clear that it was stagnating, and it wasn’t able to compete with the United States. The way it had claimed a part of that was because it had spent so much money on the arms race and weapons, it wasn’t able to be economically strong. And I think he recognized, also as the first college-educated leader of the Soviet Union, that there needed to be some reform — there needed to be some improvements not only in peoples’ ways of life, but also in the government more generally.

He decided to open up the system, both on the economic side and the political side. He allowed for more economic market initiatives. He allowed for more open discussion about political issues, and political organization and media. And that opened the floodgates. He gave a little bit of opening and freedom in these areas to a system had been very, very closed. And that took on a life of its own because many people were wanting that. So that’s, in part, why he’s considered the main cause of the downfall of both the communist system and the system in the Soviet Union.

Under the Soviet system, the states in Eastern Europe who were not officially part of the Soviet Union — like Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, etc. — were under its influence. In the past, if they wanted to go their own way, if they wanted to get rid of communism, authoritarianism and go toward Europe and be more democratic, they really weren’t allowed to do that. The Soviet Union, the army in particular, would basically come in and crush any kind of protest against communist rule. They had already done that in the ’70s and ’80s. So what Gorbachev did, which was super monumental, is he basically said in terms of foreign policy, you guys can go your own way. If Poland, or Czech or Hungary, if you decide you want to do something different, we’re not going to come in with tanks and stop you. And that was incredibly important because those countries were also communist dictatorships.

Then they had popular uprising — the rise of the everyday people in Berlin that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall where East and West Berlin were divided. The wall comes down, people are able to travel, visit their family across the wall. There were hundreds of thousands of people in the streets in Prague in Czechoslovakia, same in Poland, and so they were able to kind of go their own way through completely peaceful means, get rid of the communist system that they had and become democratic capitalist states.

I’m not saying that’s only because of Gorbachev. Obviously, it’s due to the efforts of hundreds of thousands of people in those countries. But because he wasn’t preventing them from leaving, the No. 1 significant thing it led to was Europe as a whole, not just Russia, becoming free and democratic from the period of 1989 to 1991. And those countries then have become members of the European Union. They’ve become central players in the NATO military alliance, and so they have created a Europe that is more whole and not divided.

A lot of people supported him and wanted things to go farther. But also, there were a lot of communist hardliners in his government who didn’t want any change. It became a fight within the Soviet Union between the far hardliners who didn’t want any change and who were anti-Gorbachev and those who wanted even more change. He just wants to reform it to make it work better. But when he starts to reform it, he threatens all the different sides.

The hardliners tried to have a coup on Gorbachev and get rid of him because they thought he’s too progressive, too liberal. He and another Soviet leader, Russian leader Boris Yeltsin, came in and save the day and basically ended the coup, and Yeltsin was more on the far Democratic side. So Gorbachev ended up having to leave office before the end of the Soviet Union. And Yeltsin took over wanting to reform the whole system toward democracy. Gorbachev got it started, but he wasn’t the one who sort of took it to the next level. So miraculously, without any major war or revolution, the Soviet Union falls apart into 15 countries. Ukraine is one of them.”

How was Gorbachev a different leader than Putin?

“Many commentators and scholars see Putin going after Ukraine and his invasion in 2008 of Georgia — another former Soviet republic — as Putin’s attempt to start to recreate that broader, wider Soviet system.

The other big thing, of course, is Gorbachev’s idea for opening things up. The idea of the Russia changing to be democratic went the other way. It opens under Gorbachev, but it closes back up under Putin. And you even have countries in Eastern Europe — that are not full authoritarian governments, and they haven’t gone completely the other way — having challenges to their democracy. Those main countries who are in the EU would be Poland and Hungary, and they have been sanctioned and criticized by all the Western democracies for cracking down on media, human rights, independence and freedom of the judiciary — lots of basic things that democracy is supposed to have.

We should add that it’s not just Europe, it’s the whole world. The Freedom House organization measures freedom and democracy in the world, and there’s been a decline in the number of democracies every year for the past 15 years. In ’89 and ’90, when Gorbachev and the Soviet Union were shifting, we saw an increase every year in the number of democracies around the whole world. And now we’re seeing every single year a decline, and that includes the United States, countries also like India and other major democracies. I’m not saying it’s going to fall apart in the U.S., or India or places like that. But there is a kind of challenge from various political actors.

Do you think that is related to what’s been going on with Russia or just a similar trend?

“The anti-democratic trends in the U.S. are not directly connected to Russia, but they are connected to aspects of globalization that many people feel are not benefiting them directly. Economic globalization and corporate power has meant that the middle class is not doing as well as they once were in countries like France, or the U.S. and maybe even in Russia. Changing cultural attitudes and immigration are causing backlash, and then you just have lots of populist leaders. Most of those populists are more on the anti-democratic side. They have some tendencies to be OK with rolling back, civil rights, civil liberties or things related to the media. So, again, it’s not directly related to Putin and Russia, but there are some similarities.”

Why is this something Elon students should care or learn about?

“Gorbachev is super important to everyone’s life in the U.S. because Elon students could ask their grandparents, or even their parents, what they remember about the Cold War — hiding under desks, fear of a nuclear war, huge amounts of taxpayer dollars going to fund an arms race against the Soviet Union. As a leader, Gorbachev helping to end that whole conflict is extremely important to the development of the United States and the fact that we didn’t have a nuclear war and our system came out on top, so to speak, when the communist system ended. That’s the historical answer.

It’s also good for young students to remember that what they’re seeing now with these anti-democratic trends, particularly in Russia and in Europe, were not always like that. There was another path not that long ago, which means that we shouldn’t assume that every Russian person is some kind of supporter of dictatorship. Obviously, Putin has a lot of support, but we can’t assume that every person in Russia is supporting this kind of system.”