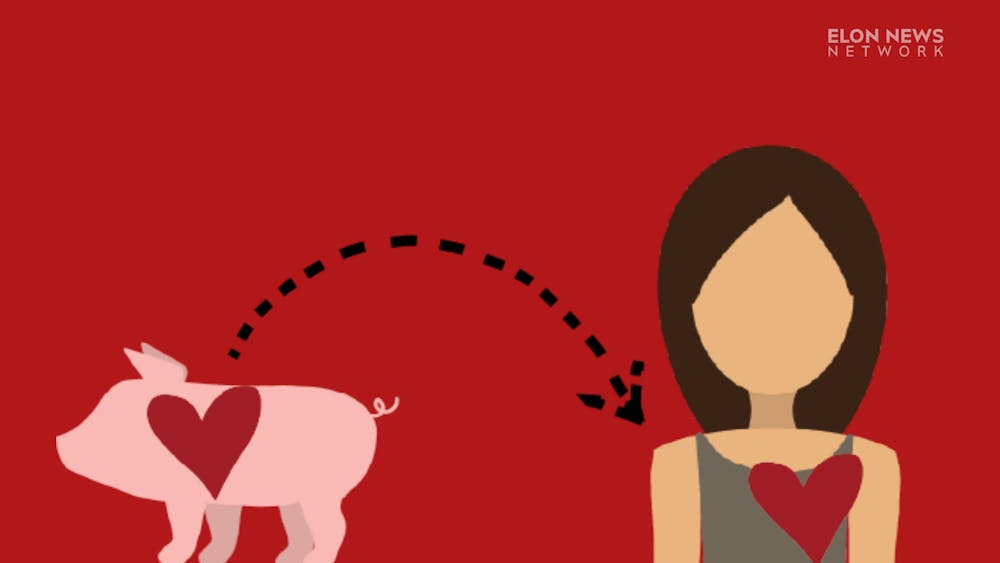

The first successful organ transplantation between a genetically-modified pig and a human patient was recorded in January. The process of performing an organ transplant between two different species is called xenotransplantation.

David Parker, lecturer in biology and lab coordinator at Elon University, discusses the practicality and possibilities of sourcing genetically modified animals for human organ transplants. Parker worked in a lab in Cambridge from ‘94 to ‘97 that was interested in the xenotransplantation process looking at the human immune system and changing the genes of a pig. Although the concept has been around for decades, the medical community has reported significant progress within the last few months.

In September 2021, surgeons at New York University Langone Health attached a kidney from a genetically modified pig to the outside of a brain-dead patient being maintained on a ventilator. Although the kidney remained on the outside of the patient’s body, it functioned as normal — producing urine and creatinine. Months later on Jan. 10, surgeons at the University of Maryland reported that they successfully transplanted a genetically-modified pig heart into a patient with heart failure.

On Jan. 20, surgeons at the University of Alabama at Birmingham reported that they successfully transplanted kidneys from yet another genetically modified pig into one of their patients. As of Jan. 31, no known issues have been reported surrounding the transplant procedures.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

How do you genetically modify a pig so that the human body doesn't reject it?

“They basically made 10 changes to the DNA of the pig. That's it and that's not very many. So they basically removed four pig genes. And those four pig genes that they removed, were genes that made proteins that are not present in humans. So these were four of the genes that cause a lot of that rejection of a pig organ. So you can kind of think about that, as you know, there's these four genes that make kind of pig-specific proteins. And you don't want any organs making those proteins if you put it in a human because they will automatically read that as not human, must destroy basically. So they knocked out — that's the scientific term, if you make a knockout of a gene, you remove it — so they removed or knocked out four genes. And then they introduced into the pig six human genes. So genes that were taken from a human being and stuck into the pig.

There's no problem taking six human genes, sticking them in a pig. The pig doesn't care. Genes are basically instructions for making proteins, and the pig would basically make the human proteins. So there's six human genes in these pigs. And they make things that basically prevent the immune response happening on that tissue. So they removed four pig genes that caused an immune response, they put in six human genes that would prevent an immune response. And that's it. And then, you can get pig organs to work in humans.”

Do they do that to the pig while it's still alive?

“You take some eggs from a sow and some sperm from whatever you call a male pig, and mix them together and you can fertilize those eggs. And then very early on, when it's just one cell big, you can make those genetic changes.

All of those pigs have those 10 changes that we talked about. They all had those four genes removed. They've all had the six genes added, and you just breed them like normal pigs and the DNA doesn't go anywhere. They probably did that over many years, right. You wouldn't make all those changes at once. So they would make a pig that has one of those changes, and then grow up. And then they do that same step on another pig and introduce a second change. Now you have a pig with two changes. And then you take another pig, you put in a third change and so on and so on until you end up with this pig that they wanted, which is a pig that has 10 changes.”

Is there anything different about the patient who receives the organ because it’s coming from a genetically modified animal?

“No, no … There are some tests that they can do to make sure that you have a low probability of rejecting a pig organ. So they’ll screen your DNA for certain things to make sure that you are unlikely to reject the organ. But apart from that, it doesn't make any difference … It’s true spare-part surgery, which has sort of been the dream of transplant surgery for about 100 years.”

Why should people care?

“Yeah, basically, because this is the bottleneck. When it comes to organ failure in America, you've got all these people that need organs — that have kidney failure or heart failure — and there's just no organs to give them. Even if you're an organ donor, you have to die under very specific circumstances in order for them to harvest your organs and give them to somebody else. Because those organs have to be very freshly harvested and all that. But with the pig stuff, it's essentially as easy as just plucking something off a shelf and plugging it into somebody. I guess the surgeon said it was a little tricky putting the heart in, because some of the plumbing was a little bit weird compared to human anatomy. But it was nothing they couldn't work around …

You could save hundreds of thousands of lives. And take a lot of stress off the health industry.”