After arriving at Elon University as an exercise science major, senior Christian Seitz had ambitions of playing soccer and incorporating his love of the sport with science.

Neither of those things happened.

Seitz found a new interest when, while enrolled his first semester in required “General Chemistry I,” he received an unexpected surprise.

“Halfway through that class, the head of the department came up to me and asked me to be a part of an invitation-only ‘General Chemistry II’ class, even though I didn’t need to take it all,” he said. “My adviser at the time said if the head of the department wants you in this class, you should take it.”

Following his enrollment in the course, Seitz made the decision to switch his major to chemistry and began to think about what he could do with a chemistry degree.

He thought back to an article he read in high school about a boy with a rare disease. The disease was assumed to be curable, but there was no cure because pharmaceutical companies would be unable to make a profit off a drug due to the small market.

“I thought of what I could do with chemistry, remembered that article and decided to dedicate my life to finding cures for those diseases, to save the lives of people who otherwise are out of hope,” Seitz said.

Applying for Lumen

After his interest sparked, Seitz decided to apply for one of Elon’s prestigious academic honors — the Lumen Prize, which is awarded to a select group of students and provides them with $15,000 to assist in financing academic endeavors as well as research projects, like the one Seitz had begun to develop with his now-mentor Joel Karty, associate professor of chemistry.

Karty originally came up with an idea to model how atoms — called enolate anions — behave. According to Seitz, these atoms are important intermediates in organic chemistry, so they are found in many different areas of life.

Together, Karty and Seitz turned the idea into a strong proposal. The project is a basic research project, meaning there is not necessarily a specific problem trying to be solved, but rather simply trying to find out more about something.

“There is this really important molecule [enolate anions] in organic chemistry, and it will react differently in a gas solution than it would in a liquid solution,” Seitz said. “We know that there are these two effects going on that influence why it reacts differently. We know they are both going on but we don’t know how much contributes to this happening, and how much contributes to that happening. I’m trying to figure out exactly how much each of those contribute to the reaction, in the gas phase.”

The research Seitz does here at Elon is all theoretical. Instead of working in a lab, all of his work is done on a computer, giving him more freedom for when he can do his work with access to the fastest computers on Elon’s campus.

Their research has been going on for a year and half and is expected to finish up during either Winter Term or the beginning of spring.

Taking research off campus

In addition to his research, Seitz has embarked on two journeys abroad to broaden his knowledge.

“Christian has very inquisitive nature and he uses his knowledge to try to make a positive difference in the world,” said sophomore and close friend Alexander Ball.

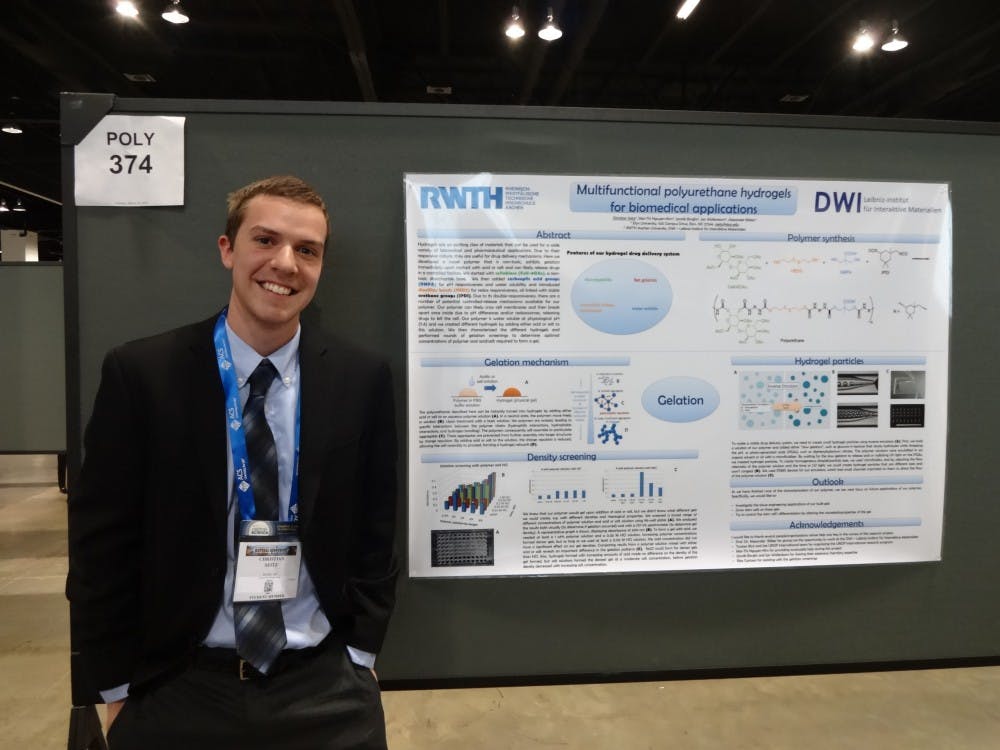

Two summers ago, Seitz decided to explore an area of chemistry he was not as familiar with. With that in mind, he applied and was accepted to a project abroad in Germany that would apply to his work later in his career as a chemist.

“We were trying to find more efficient ways to carry cancer drugs to cancer cells and to kill them, as opposed to killing the surrounding cells,” Seitz said. “It was an interesting scientific project for me as well because I felt like I could use stuff I learned in that project later on when I’m trying to design a drug for rare disease, because I might have the drug — but I need to know some way of getting the drug in the body and exactly where it has to go.”

After participating in this project, Seitz knew this is what he wanted to be doing for the rest of his career.

This past summer Seitz traveled across the country to the California Institute of Technology for the Amgen Scholars Program. The professors had been working on it for 15 years before Seitz joined the Amgen program — one of the most prestigious programs in the country.

He was interested in the project because it was classified as computational biochemistry, which looks into using computer simulation to help figure out chemistry problems — another side of chemistry that he always wanted to explore.

“I was very interested in the theory behind it,” Seitz said. “[Fifty years down the road], this sort of work could be used to eliminate side effects of about one-third of the drugs on the market right now.”

Since the work he did at Caltech was all computational, Seitz still has the ability to contribute to the project from here at Elon.

As graduation approaches, Seitz looks back at the shining moment in his chemistry career — when he received the email that notified him that he had won the Lumen Prize.

After accepting admittance at Elon, Seitz decided to apply to the Fellows programs, thinking he would be academically challenged in the programs. When he was declined a spot, he was disappointed, but still chose to apply for the Lumen Prize.

“I decided to use the Lumen Prize as something to prove to myself that I was still worth while as scientist — as an academic,” said Seitz. “Winning the Lumen Prize vindicated what I thought was true, that I was actually capable of doing really awesome stuff. So it showed me that even if no one believed in me, if I knew inside that I could, then I definitely can, and I shouldn’t listen to anyone else who tells me I can’t.”