Imagine a college student having 5 million dollars in the palm of their hand. For some student athletes like AJ Dybantsa — the point guard for the BYU Cougars — it is not something they have to imagine. That is the reality of the NCAA’s Name, Image, and Likeness policy for college athletes like Dybantsa, who will make 4.4 million dollars through NIL over the next 12 months.

While some athletes make jaw-dropping amounts of money, others generate just enough to stay afloat while participating in their college sport.

Caden Strickland, a senior on Elon University’s men’s cross country team, said it wouldn’t be possible to put the amount of hours into running that he does each day if he wasn’t able to make money from just being himself.

“This takes up, essentially, our entire schedule,” Strickland said. “To have the opportunity to put my name out there and make money off of what I love doing helps me a lot financially.”

Strickland said athletes like himself are often unable to manage a job on or off campus because they have limited time outside of school and sports.

“The majority of the season I was running 90 miles a week, obviously with a full class load,” Strickland said. “That is not enough time for me to work an on-campus job or do anything else to make a reliable source of income.”

According to the NCAA’s website, NIL “empowers college athletes to earn income from business ventures and personal brand while still in school.”

In 2021, the NCAA adopted a NIL policy that allowed students to profit from their brands while competing in college athletics. NIL is a tool that allows student-athletes to make money on the side of their sport. With the addition of the policy change, athletes can now partake in growing their own personal NIL without violating college athletic guidelines.

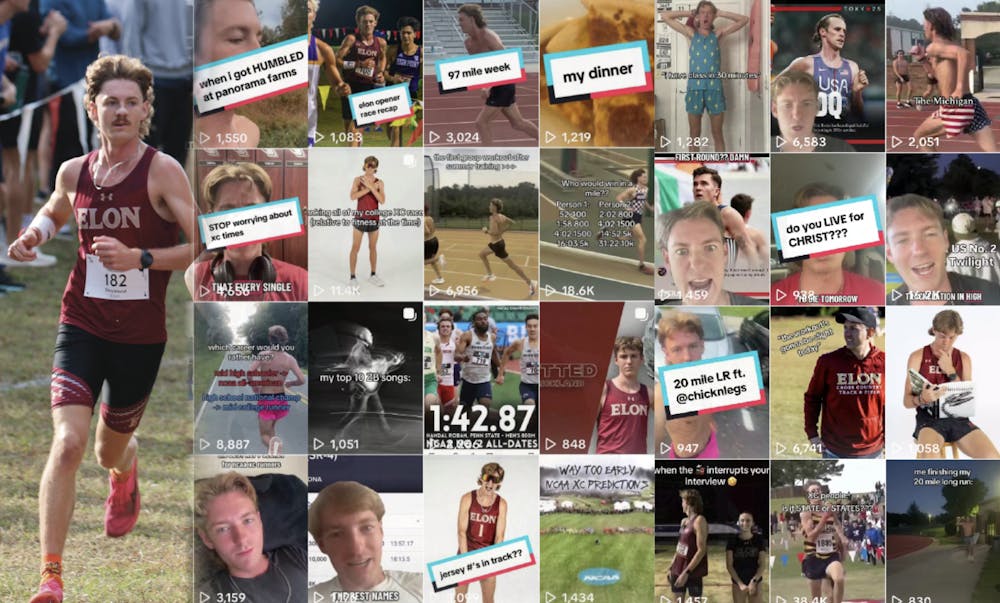

Strickland said the dream of establishing his name on social media started during the spring semester last year. Strickland would film weekly vlogs of his practice schedule and mileage for the week and upload them on both Instagram and TikTok. Although it was a struggle at first, Strickland saw his social media success take off over the summer when he was living on campus. He said the loneliness of the empty campus pushed him to upload more content.

“I was bored,” Strickland said. “I just took my phone out and started recording all of this stupid, silly content, and pushing it out there.”

Khirey Walker, a sport management professor at Elon and a former college athlete, said NIL was long overdue for student athletes.

“Being able to make money, regardless of the experience, is necessary,” Walker said. “Student athletes have to commit so much of themselves to the universities, so being able to profit off of that and connecting that through the experiences that they have is really necessary.”

While it is a benefit for athletes, NIL can sometimes create distractions for the students. Walker said the ability to transfer helps athletes chase their dreams of getting to the next level, but it can also take away from the experience they are currently in.

“When you are at a university and playing for a sports team, that is where your heart should be,” Walker said. “If you are playing your season for a team and already looking elsewhere, you are short-changing that team.”

It’s not just on the court that athletes can leave experience behind; Walker also emphasized the importance of the academic experience for college athletes.

“There is no college sport without college,” Walker said. “Someday, your career is going to end. Those shoes are going to come off, and that degree is going to be as valuable as you made it in your time in college.”

Since the NCAA adopted the policy for NIL in 2021, the ability for student-athletes to make money while in college has taken off. In the last six months, the NCAA introduced the “NCAA NIL Assist.” The assist platform is used to help student-athletes “understand and make informed decisions about NIL,” according to the NCAA’s website.

NIL generates millions of dollars in revenue solely because of a player’s status for some college athletes, such as Dybantsa. But for Strickland, it took time to get to where he is today.

After a few months of hard work and seeing his posts on Instagram and TikTok climb to upward of 100,000 views and even 1 million views, Strickland was able to land a deal with ChicknLegs Running — an apparel company geared toward distance runners. Over the summer, Sydney Seymour, a former All-American Runner with NC State University, reached out to Strickland with an opportunity for a partnership at ChickenLegs. Strickland said the ability to combine his passion for running with his newfound social media success is the best of both worlds.

“An idea pops into my head, I grab the camera and I post it,” Strickland said. “The extra stipend coming in helps me a whole lot.”

Strickland has found success in the running community, but Walker said athletes should also take advantage of the college community, as well as where they grew up, to capitalize on their audiences and supporters.

“That is where your brand is really strong, your home area, where you went to high school,” Walker said. “I think a lot of student athletes tend to forget about that.”

Walker said even though his days playing football are behind him, he has his eyes set on where he would have taken advantage of the NIL opportunities around Elon.

“I would have gone to any local restaurant that supports Elon athletics,” Walker said. “I joke with my students all the time, but I’m dead serious, Biscuitville would’ve been my first one.”

Strickland has also turned his Photoshop skills into his own graphic design business on Instagram, where he builds commitment graphics for athletes. He said the ability to do something like that would not have been possible without the passing of the NIL policy in 2021.

“It’s not something that I would have been able to do four years ago,” Strickland said.

Strickland said the addition of NIL has been a step in the right direction for the NCAA, and he hopes more opportunities for athletes will present themselves in the future.

“At the end of the day, we are not different than these other students,” Strickland said. “So why should they be able to do something that we’re not?”

As for Walker, he said there is still a long road to perfecting the NIL policy in college sports.

“I am really anxious to see how things are going to continue to go,” Walker said. “Especially with the amount of money and how things are rapidly changing.”