In the corner of a dim T-shirt warehouse in Burlington, N.C., surrounded by buckets of colored dye and paint-splattered rotating machines, are rows of broccoli sprouts, barely an inch tall.

They lean toward the sliding door in front of them, where, on the other side, a handful of chickens nervously peck at company shop fruits and vegetables that didn’t make it to the register in time.

Back inside, Eric Henry, wearing a gray shirt reading “TS Designs,” works on a PowerPoint at his desk. The late afternoon sun brightens the room. The lights are off.

The first slide on his computer reads, “98%.”

“That’s the percentage of clothes we buy that are made overseas,” he says.

Henry is the president of TS Designs, an apparel manufacturing and screen-printing company focused on sustainable, high quality and long-lasting T-shirts. Instead of reaching overseas for cheap labor like most apparel companies, TS Designs receives almost all its blank T-shirts from the Carolinas. The entire process – from farm to finished product – spans only 600 miles, just a fraction of the distance most other shirts travel.

While this has a positive environmental, social and economic impact on the United States, TS Design customers do have to pay a little extra.

“It’s not that our T-shirts cost too much,” Henry said. “I will compete with any apparel company in the world. Just don’t bring price to the table. When people come here, if you’re only interested in the lowest possible price, we’ll have a short conversation.”

The cost of labor in the United States is much higher than what is offered to workers in countries like China and Bangladesh. This is because the United States produces better quality materials in factories where Americans require higher salaries. By paying more for better clothing, American shoppers allow for more jobs in the country and, with the methods TS Designs implemented, a healthier environment, Henry said. But many people do not understand the process or impact involved with buying clothing.

“The problem we have is that we get so infatuated with the price, we never ask other questions,” Henry said.

The aspects of a clothing purchase that aren’t questioned can sometimes be harmful, and even lethal, to those working in factories across the globe.

Henry said business can be a component of positive change, but Americans have to look at it differently than they do now and need examples to look up to and mimic.

TS Designs is striving to be that business.

Check the tag

When deciding between two similar products, most people will examine the price tag and go to the register with the cheaper item. But price isn’t limited to just that product. There is a price on production.

This is why TS Designs uses North Carolina labor at about $15 an hour. Having North Carolinians create the shirts instead of factories overseas keeps more jobs in the state and boosts the economy, even though the products cost more.

For a while in the early 1990s, TS Designs flourished. It had big corporations, like Nike and Gap, buying shirts from them. While creating mass materials for these companies, TS Designs was also able to generate a profit and support sustainable apparel manufacturing in the community.

“I felt like, as a business, we had to be good stewards of the Earth,” Henry said. “Those characteristics, instincts, were part of our business but nobody really cared about it – Nike, Tommy, Gap, Polo. All they cared about was that we produced a quality product on time.”

The normal business model of the time didn’t look beyond that aspect of production and that employees had access to health care and retirement. But TS Designs went beyond these requirements. The company focused on environmental stewardship, produced a high-quality, competitively priced product, and had employee benefits. By the mid-1990s, it had more than 100 employees.

But in 1994, everything changed.

The United States had signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, better known as NAFTA, in late 1994 and it went into effect the following January. This agreement resulted in a massive shift in the apparel industry. It was designed to promote free and fair trade between the three signees – Mexico, Canada and the United States. It also caused the “de-industrialization” of the United States, meaning more American jobs were displaced outside the country.

Apparel production moved almost instantly outside the United States’ borders, where labor was cheaper. This ended up bankrupting many small businesses and unemployed tens of thousands of people.

“I saw my business, over the period of two years, go from 100 employees to 14,” Henry said. “We were devastated because the business that we built – there was just no future for it.”

The brands TS Designs produced shirts for could not get the apparel overseas fast enough. It seemed like there weren’t any reasons to make apparel in the United States since a company would need to outsource its highest cost – which would be labor for TS Designs – to cheaper sources.

Most western brands that had previously worked with TS Designs, such as Tommy Hilfiger, Nike, Gap, Polo, Ralph Lauren and Adidas, changed their business models to get their labor offshore.

Henry also had to change the focus of TS Designs while ensuring the business could still support itself and be involved in the community. One of Henry’s friends suggested he look into using a triple bottom line sustainable business model. It focuses on the three P’s: people, planet and profit. After analyzing the model and comparing it to TS Designs’ current plan, Henry realized most of the components were already in place.

TS Designs worked to build up this model and started to spread interest in sustainability in the community.

TS Designs worked to build up this model and started to spread interest in sustainability in the community.

With this new method in his head, Henry started examining the idea that the price and real cost of production had starkly different definitions. The cost of production was something American shoppers rarely took into account.

This concept became tragically clear on the morning of April 24, 2013, when an eight-story Bangladeshi apparel factory collapsed, killing more than 1,100 people and leaving more than 2,500 injured.

“Why does that happen? 26 cents an hour is why that happens,” Henry said.

Only the concrete flooring remained intact. It was considered the worst apparel disaster in history.

“People say, ‘oh my God, how does this happen? Why do we let this happen?’” Henry said. “Real simple economics: We pay those people 26 cents per hour. So don’t be surprised. When you have a publicly traded company that’s in business to maximize return for their shareholders, where are [they] going to go? [They’re] going to go to get the cheapest labor.”

Relatives of those lost in the rubble were given $700 as death benefits if they could prove they had a family member who died.

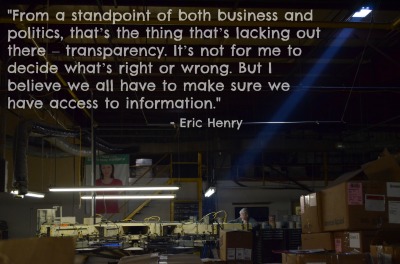

Henry did not use the event as a catalyst to change people’s minds. He said it was not his duty to tell people they shouldn’t buy something made in another country. He said he just wanted, and still wants, the information out there for public knowledge.

After the tragedy, Henry said people started realizing what the term “cheap” really meant.

“Who was responsible for that cost of [Bangladeshis] manufacturing in a facility that should never have been built?” he said. “That cost was not incurred or passed along.”

The cost of T-shirts from TS Designs is more than other custom T-shirt companies, but Henry said this shouldn’t be the deciding factor.

“Most people don’t understand our value proposition and only understand price,” Henry said. “They’re ordering 100 shirts for some event and they’ve been used to paying X and they see our prices are Y or X2 and they don’t understand the difference between a domestic-made product and an overseas product. Organic cotton and conventional cotton. Water-based and plastic.”

It’s similar to purchasing food from a fast food restaurant. The food is fast and cheap. But the cost of environmental degradation, obesity and energy is rarely acknowledged, Henry said.

“We run around the world chasing cheap labor so we benefit from it,” he said. “We have a broken apparel system.”

Building meaningful communities

Young saplings were one of the first additions to the new TS Designs building. When the company bought the squat building they currently own, employees planted young saplings around a grassy area around the front door.

That was 24 years ago and today, the trees are tall enough to provide ample shade.

The building sits off a small road in Burlington. It’s easy to miss it, but it’s alive with activity inside. White shirts are printed Monday through Thursday. Friday is dedicated to garment dyeing the materials. The prints are in the fabric, not on it, so buyers don’t have the scratchy material that cracks and peels after a few rounds in the washing machine, Henry said.

Before heading off to their various destinations, the shirts must go through an aggressive inspection process to ensure there are no holes or defects.

Behind the building, there is a community garden, chickens and wooden bee hives. The chickens live in a fenced-in area where they help make the soil fertile by pecking and scratching at it. Henry has a similar arrangement at his near-net-zero-energy home.

“All the eggs and all the vegetable in that garden go back to our employees, including the honey [from the bees] for them to use,” Henry said.

Henry said he is interested in being a part of his community and changing the way people see the apparel industry. With clothing, once people understand a company is legitimate, they’re willing to help you, even with things not related to the industry, Henry said.

“I have everything from bee consultants to chicken consultants,” he said. “These are people that are passionate.”

One of the people Henry connected with was Ronnie Burelson, a cotton farmer in New London, N.C. Henry asked if TS Designs could buy cotton from him and he accepted the offer. This partnership would become part of a collaboration of farmers and production companies known as Cotton of the Carolinas.

Instead of traveling 17,000 miles, like most other T-shirts, all TS Designs apparel travels only 600, prompting their tagline, “Dirt to Shirt.” This collaboration produces better quality and longer-lasting shirts. It also impacts 500 American jobs.

“What happens with [being] local is you’re keeping the money in your community,” Henry said. “You’re supporting the people you know.”

The entire process, from the farm to the dyeing procedure, is transparent. A buyer can use a style number on their T-shirt tag and use Google Maps to find exactly where each step of the process happened, as well as that person’s contact information. The program focuses on local economies, little transportation and complete transparency. TS Designs is the only T-shirt brand that offers this.

“We need to know where things are coming from, where our money is going [and] where things are made, but I’m very concerned with the lack of transparency that we’re having in our manufacturing and political system,” Henry said. “If we had better transparency, we might not have had that situation in Bangladesh.”

Henry’s interest in all things local narrows all the way down to the TS Designs building. The neighborly sense of community Henry shaped in the company has gone a long way.

The company’s social media director, Jen Busfield, said the garden behind the building is one of the many ways TS Designs keeps employees connected to the soil. The garden provides extra organic vegetables for employee use and also teaches a life skill.

“It’s teaching us how to be connected to the soil, which matters, especially for our in-house products that are grown here in North Carolina,” she said. “It matters in a lot of ways.”

As the social media director, Busfield knows several other companies that, like TS Designs, have a triple bottom line and a focus beyond monetary gain.

“Whether that’s giving back to charities as social enrichment or if that’s in the way they process their goods, [the companies] are paying attention to how much they may be taking,” she said.

With all the innovations TS Designs has and continues to make, there is a definite need for an ambassador, Busfield said.

“It needs a cheerleader because it’s not a popular message,” she said. “It’s not a popular product. Extra work – who wants to do that? Pay more for a product – who wants to do that? But when you hear the story and you see [Eric’s] excitement and how passionate he is about the choices that his company has made and the choices he makes as an individual working together – it’s awe-inspiring.”

Travis Clark, the screen department manager, said this direction is definitely the one the company, and other American stores, should be heading toward.

Henry is a big believer of this, Clark said. But, business aside, he’s also a good friend.

Even though his employees would never know about it, Henry also does a lot of behind-the-scene work that benefits the company, Clark said.

Clark had a heart attack in 2010 and about 15 minutes after his surgery, he said his family and Henry were standing besides his bed to make sure he was doing well.

“He’s helped me out,” Clark said. “He’s done a lot for me. He’s a good man. Eric Henry is a good man.”

Stirring significant change

On a warm afternoon toward the end of February, Henry stood on a red, circular carpet on a stage at Elon University in North Carolina.

Students from the university had invited him and three other pioneers in their field to speak at a TEDx event. The theme of this lecture, which was an independently organized version of the popular TED Talks, was “Innovation into Practice.”

Two television sets on either side of him lit up with a familiar PowerPoint slide. They read, “98%.”

“I remember what the apparel business used to be,” Henry said, after explaining what 98 percent stood for. “I lived through that. I remember when it used to be 98 percent [made] here. Now, it’s 98 percent away.”

His lecture ended with a homework assignment: Look at labels on clothing. Find where they’re made. Do research.

The TEDx event is not Henry’s only connection to the school. He has been involved with the Koury Business Center alongside many Elon professors, like Kevin O’Mara.

O’Mara, a professor of management, said he sees more businesses moving toward eco-friendliness and positive social impact.

“There are a lot of reasons for companies to want to do this,” O’Mara said. “There are very little negative reasons other than high cost.”

O’Mara likes Henry’s business plan because there is an actual business side of the company. It’s not just a cause Henry supports in his free time. He works with TS Designs from an economic point-of-view and knows it needs to pay off in the short term and long term, O’Mara said.

“This idea of throwing it back to the community, getting back to nature and the environment, finding ways to use this as an advantage rather than treat it as a social cause – I think it’s enlightening,” O’Mara said. “If it’s purely a cause, then there’s a cost associated with it. But if it happens to be something that works, as well as supports the environment and the people in this community, then it’s a win-win. What I think Eric is trying to capture is a lot of these win-win opportunities heavily doused on the side of environmental concerns, but not to the point where it would jeopardize his business.”

Henry said he enjoys engaging with students at Elon and beyond because they hold control of the future and will face challenges he had never confronted before. But once people start understanding the problem at hand, they can start contributing to change, Henry said.

“If you don’t know about something, fine, I’ll cut you a lot of slack,” Henry said. “But once you’re in light and aware of what you’re doing, that action has a negative impact on others and you’re part of the problem now.”

“If you don’t know about something, fine, I’ll cut you a lot of slack,” Henry said. “But once you’re in light and aware of what you’re doing, that action has a negative impact on others and you’re part of the problem now.”

But Henry said he sees a lot of young people looking for more from life than a big house and a nice car.

“They also understand, which I’m a big believer of, that success determines how we all do,” Henry said. “If I’m the only one successful and have a good life and everything around sucks, unfortunately my life will suck because what makes us is our community. That’s what drives me to what I want to do. This is where I live. This is where I work.”

Henry also plays a prominent role in the Burlington community. He founded the Burlington Biodiesel Co-op and Company Shops Market, a co-op grocery market where all the food is made locally. He is also working to get Burlington’s Beer Works Co-op off the ground. These shops are part of a plan to revitalize downtown Burlington and connect the community to local resources with community-owed stores.

Henry doesn’t look at this venture as a way to change the whole world and take the city back from superstores. He knows he will not convince every person he talks with to pay closer attention to the benefits of local products and the real cost of manufacturing outside the United States.

While he is not expecting all the jobs to return to America, he said he knows America can do better than 98 percent.

“I tell people it’s not all coming back,” he said. “We live in a global marketplace and I’m not going to fool myself, but we need to balance the scales.”

From awareness to action

Change starts when a switch is turned on or off, like a light bulb, after being presented with new, factual information.

In TS Designs’ case, the light switch is always off, but ideas are constantly bouncing around. Large windows let in plenty of sunlight and the electricity bill remains low.

“Typically we would have a meeting in an office and rarely do the lights come on,” Henry said. “If we need to, we’ll put them on, but it’s that awareness factor.”

Sometimes the consequences from decisions are invisible, which is why Americans aren’t paying the true economic cost of their choices, Henry said. While some people have a deep-rooted passion for sustainable manufacturing, others are not interested. And that’s okay, Henry said. With the amount of evidence that reveals society is headed in the wrong direction, Henry said he doesn’t have time to worry about those who are still on the fence.

“I’m not interested in getting involved with people that still don’t think it’s important,” Henry said. “That’s fine. Do your thing. I’m going to work with the people that say, ‘we have a problem. Let’s work it out.’”

This mindset is what created Cotton of the Carolinas and the multiple co-ops in Burlington.

Companies like these hold a lot of power for change, but their transparency is crucial.

Companies like these hold a lot of power for change, but their transparency is crucial.

“There is no question I won’t answer, there is no place I won’t take you,” Henry said. “We’re not a perfect company. There’s always room for improvement. There’s always room to do a better job and change and all that and we want to be open to that.”

This is why sustainability is a journey, not a destination, Henry said. It takes time and patience to change a nation’s – or even a community’s – mindset.

Henry said there is comfort in the change since it encourages positive behavior in a community.

“We’re all in this thing together,” he said. “We have this one planet. But we become disconnected. We don’t know where our power comes from. We don’t know where our food comes from. We don’t know where our clothes come from.”

But this can change over the next few decades, just like the gradual acceptance of climate change and eco-friendly light bulbs. Without similar improvement and awareness about the apparel industry, things are only going to get worse, he said.

Luckily for Americans, it’s easy to access that information. Henry said he is thankful for that, but not many people will take the time to research the products they purchase. Finding the origin of everyday products becomes a chore. For many, it’s easier to ignore. But this attitude leads to disasters like the factory collapse in Bangladesh.

“We are ultimately responsible to the planet and society so we have to do our part and get off this mindless treadmill that everybody is on,” Henry said. “It starts with you. It starts with knowing.”