Affirmative action is on the chopping block, and where the cleaver falls is up the Supreme Court justices. Justice Elena Kagan removed herself from the case, presumably because of a conflict of interests, leaving eight justices to make the critical decision.

Affirmative action is on the chopping block, and where the cleaver falls is up the Supreme Court justices. Justice Elena Kagan removed herself from the case, presumably because of a conflict of interests, leaving eight justices to make the critical decision.

Today, the conservatives in the High Court, including Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Antonin Scalia, criticized the race-conscious admission policy of the University of Texas at Austin. The case was brought forth by Abigail Fisher, a student who was denied admission to the university in 2008.

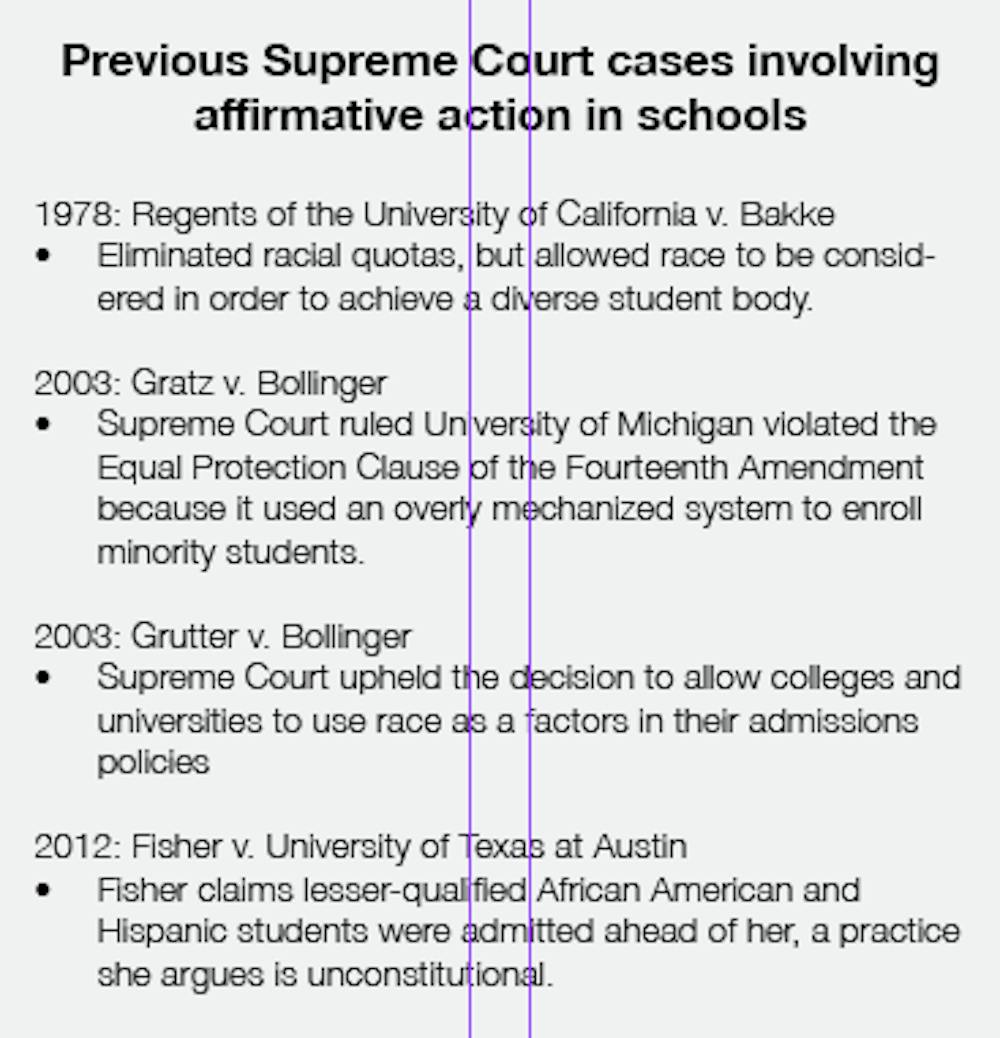

Fisher claims lesser-qualified African American and Hispanic students were admitted ahead of her, a practice she argues is unconstitutional. If the majority of the Supreme Court sides with Fisher, the affirmative action policies used by many colleges across the country may either continue in an altered form or cease to exist at all.

Private institutions like Elon University reserve the right to structure their admissions policies as they see fit, and most would likely remain unscathed if the Supreme Court deemed Affirmative Action policies unconstitutional. But according to Robert Parrish, assistant professor of law at the Elon School of Law, such a ruling could alter the campus demographics of colleges across the state of North Carolina.

“We will see a huge decrease in matriculation or minority students, especially African Americans,” he said. “That would affect a whole generation of students.”

Parrish cited matriculation rates of minority students at the Universities Of California in Los Angeles, San Diego and Berkeley after the state outlawed race-based admissions policies in 1993. The rates have fallen between 25 and 40 percent, he said.

Such statistics lend credence to the idea that inclusive and diverse campus environments cannot be created through race-neutral admissions, an argument stated by many colleges. Lisa Keegan, interim dean of admissions at Elon, said she thinks at least some levels of diversity can be achieved by other means.

“I’ve never worked at a large institution that receives 50,000 or 75,000 applications, so I have no idea what that would be like,” she said. “Everyone has a different approaches, but you can make sure you remain accessible to all students through college fairs and you can maybe look at it from the recruitment angle.”

Parrish agrees there are other ways to foster diversity on college campuses, but only to a certain degree.

“When you go to a race-neutral policy, you can in some ways manipulate student diversity in a way to maintain diversity to some extent, but in every way, it’s been less effective than Affirmative Action,” he said. “There are methods for trying to increase diversity, but none of those methods have been perfect and it takes the combination, the cocktail of methods. What we’ve seen so far is no one idea has worked.”

But sophomore Bridget Creel said she thinks Affirmative Action should not be an option afforded colleges trying to build a diverse student body.

“I don’t think ethnicity should play a role in college admissions at all,” she said. “If you have the grades and the work ethic, that should be all that matters.”

But if minority enrollment rates were to decrease in North Carolina’s public universities, Parrish said students might be deterred from applying to those schools.

“I would say anecdotally, I see a number of students who come to this university in particular because they see it as a place that diversity matters,” he said. “I do think there is a contingent of individuals that may not come to a university knowing it’s not a diverse place.”

In his opinion, the same might be true for minority students.

“Minority students will feel less likely to come to a place that doesn’t seem to value diversity very much,” he said. “No one wants to feel like the spokesperson of their race.”

But the Supreme Court may not slash the policy entirely. The justices debated today the definition of “critical mass,” a term coined in the 2003 Grutter vs. Bollinger case. The court ruled institutions of higher education could employ Affirmative Action policies to obtain a “critical mass” of minority students, and Justice Samuel Alito stressed the need for a more concrete enrollment standard.

“’Critical mass’ is a very mushy standard, and the conservative majority in the court isn’t comfortable with it,” Parrish said. “The court is going to either say diversity at the higher state level is not a compelling interest or it will nibble at the edges and limit what these programs can do and limit the role of race in admissions decisions.”

Though the justices’ decision, which will likely be made before June, won’t greatly affect private schools, Keegan said she thinks these institutions are following the case just as closely as public institutions.

“Private schools are not under the microscope in the same way, but it will give everyone pause as they think about the admissions process,” she said. “I’m proud of the way we have such a holistic view of our applications.”