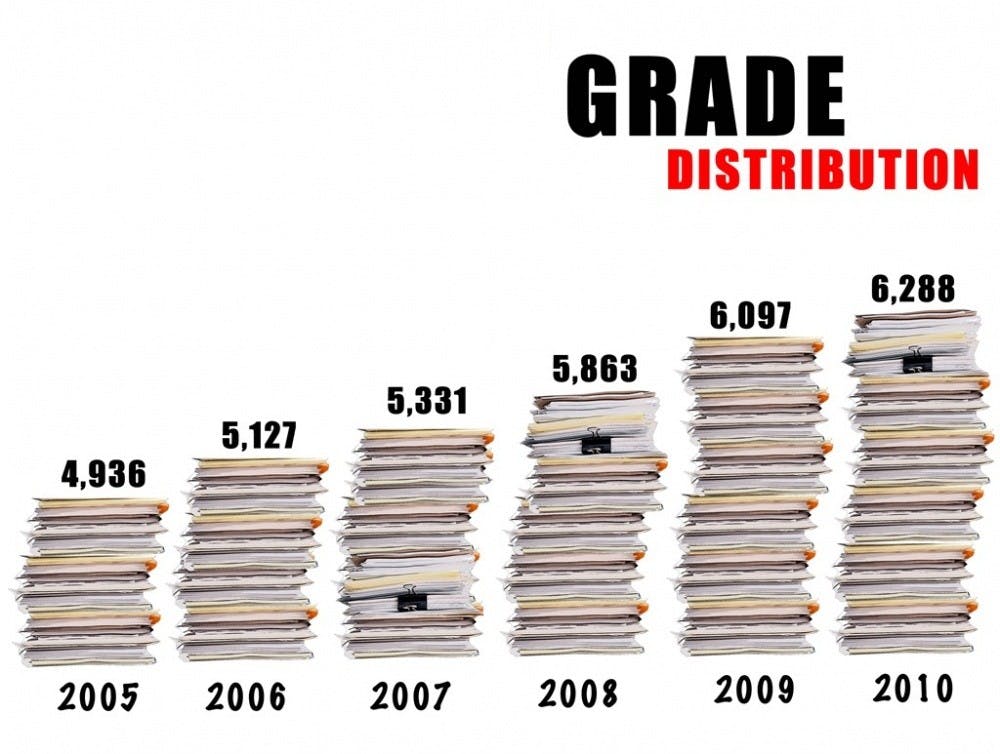

Following the recent trend in distinguished grades at Elon University, 25 percent of grades given during the fall 2010 semester were A's while 12.8 percent were B's, bringing the standard GPA to 3.17.

Steven House, provost and vice president for academic affairs, said his worries are more centered on the rise of A's and B's among students rather than the increased GPA.

"The average grade percentage being 3.17 doesn't really bother me at all," House said. "What bothers me is the percentage of A's. If you look at our catalog, it says the A is reserved for distinguished performance, and when a quarter of the students are getting a distinguished performance, it raises the question of how distinguished an A really is. It seems that faculty are doing a disservice to their very good students that are really doing distinguished work."

Peter Felten, assistant Provost and director of the Center for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning, said he believes an issue lies in the understanding of what grading is about and what its purposes serve.

"I think we don't have a common understanding of what grades are for," Felten said. "Within the same department, there are some instances where there are two faculty teaching the same course to the same number of students, but each have very different grading methods. One may be curved, while the other is criterion-based, and to me, that doesn't seem entirely fair. I think it would be helpful if faculty within the same department agreed on what grades are actually for."

House said he and faculty have pondered several reasons for the grade increases in order to better understand how to address the issue.

"There are a number of reasons that people use to explain why grades are going up," he said. "One, students are smarter and faculty are better teachers. Faculty teach differently then they used to, i.e. they used to say, 'Hand in your paper, I'm going to grade it, and that's your grade.' Now, I give it back to you with some suggestions so it's more back and forth, back and forth."

In response to the suggestions, House said the administration has advised faculty to execute more rigorous academic teaching and supply thoroughly descriptive rubrics.

"I think this is a faculty-led initiative," he said. "They're the ones who are going to have to be responsible for making sure they give rigorous exams with appropriate grading to give good feedback to students and recognize them for the work they're earning. That being said, my job will be to back them up, and right now, I think the best way to address this issue is to be transparent with the information."

As the university executes policies pertaining to minimum GPAs, both Glenda Crawford, director of the Teaching Fellows, and Maureen Vandermaas-Peeler, director of the Honors program, agreed students feel pressure to earn A's and B's to remain in good standing within academic programs. They also said students' tensions should not place pressures on faculty to easily hand over higher grades.

"The requirements of the (Honors Fellows) program make it incumbent on the students to achieve and are not intended to put any pressure on faculty assigning grades," Vandermaas-Peeler said. "A combination of hard work, ability and intellectual curiosity enabled students to gain admittance into the program, and we expect these qualities to be enhanced in college."

Crawford said she believes it is important to address what grades symbolize and to distinguish the difference between different letter grades.

"It's important to pay attention to what middle work is," Crawford said. "If you just meet expectations and do exactly what you're supposed to do, that's B (grade) work. A (grade) work is more about going above and beyond and exceeding expectations, and we really try to stress that."

In addressing possible solutions, when asked if a grading quota would assist the process of decreasing the number of A's received, House said he believes the policy would be unfair to enforce, because its limitation could hinder the success of hard-working students in classes.

"I think if a student has earned a distinguished grade, by saying you can't give it to them because you already have so many A's is unfair, and therefore, I'm against it," he said.

House said he believes if students were to understand that the grading process doesn't begin at the A level, it would help solve some grading issues.

"You start with a C," he said. "You start with what is considered satisfactory work, and if a student goes above and beyond that, you get extra points. You work your way up. Faculty don't start at an A and mark points off."

Similarly, both Vandermaas-Peeler and Felten addressed how many students often came to Elon with the expectation of receiving A's and B's because they were accustomed to earning high marks in high school.

"Sometimes (students) are shocked that the effort they put into their courses does not always correspond to an exceptional grade," Vandermaas-Peeler said. "I think students, and sometimes faculty, tend to forget that A's are considered exceptional and that studying hard doesn't always mean your product was exceptional."