Great sci-fi isn’t built upon the bluster of battlecrusiers exchanging laser fire while orbiting far-flung planets, nor is it initially constructed with an ornate, complex back-story with confounding names and outlandish technological advancements.

Great sci-fi hinges upon changing just a few major elements in the universe the visionary is creating, and then observing and analyzing natural human responses to these strange and wondrous alterations. All of the robots, lightsabers and ray guns in the world cannot corral a intriguing and compelling story, instead, truly engaging work uses them as garnish atop a story that ultimately hinges upon character interaction, not arbitrary set-pieces and tedious explosions.

Plenty has been said about District 9, and the praise has come in swarms, both from the critics corner and from the box office returns. So I won’t talk about just how fantastic the movie is, how its direction perfectly fluctuates between brutal realism, heartbreak and fantastically captivating action, how its allegorical and simple premise which, although dealing with familiar themes, is nonetheless refreshing.

Instead, I’d like to highlight something that I haven’t seen discussed much in the criticism or discussion of the film (and if it has, do be kind, I can’t be privy the Internet in its entirety).

For all of the bluster about apartheid and racism, and how they play into District 9, the theme that I found to be ultimately the most interesting was that of the role of the individual in society. As we learn in the film, the alien Prawns that land on Earth are a sort of worker class, cut off somehow from their species’ hierarchy and left in a barbaric state as a result of this isolation. They are an anonymous group driven primarily by a need to survive (and eat cat food).

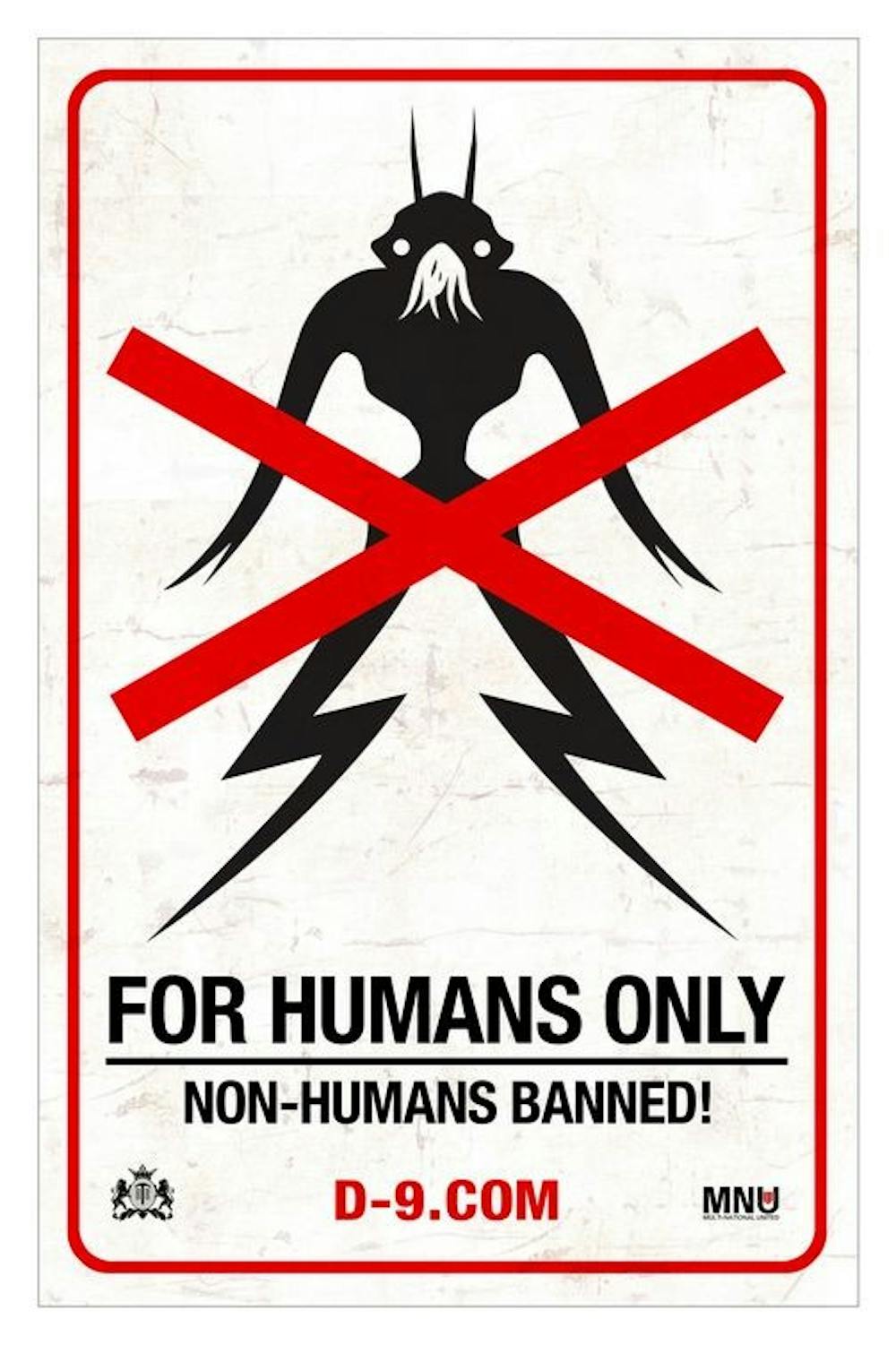

The main character, Vickis, may appear to some as an equally anonymous peon on a corporate ladder (the appropriately evil ladder of the MNU), but he is nonetheless an individual, a man endearingly lovestruck and devoted to his wife, a slightly awkward man whose brief position of power results in his passing of some wisdom, a few stumbles, all of the typical stuff that makes up the human condition.

Then, of course, he starts turning into a Prawn, MNU wants to use him to gain access to advanced Prawn weaponry and with his escape, Vikis is immediately ostracized from society, from his job, from his wife and from the societal hierarchy that he had previously depended on. As the film progresses, we witness him become increasingly self-reliant, impulsive, violent and willing to do anything to return to his role in society until he realizes that its an impossibility, until he turns his back on the world he resided in entirely. What the audience witnesses is a man who endures exile, fights against said exile and who ultimately loses his humanity in a literal, and arguably moral sense.

On the other hand, the main Prawn character, Christopher Johnson, is depicted as a uniquely driven, devoted being, still maintaining loose ties to the remainder of his far-flung race and a loving relationship with his son. As the film runs its course, Christopher morphs from the typical likeable alien with ulterior motives into arguably human character. His devotion to his people and their freedom is reminiscent of the hundreds of other freedom fighters whose lives and sacrifices have been portrayed on film, and his relationship with his son is ultimately the most emotional and pure in the entire film.

But what, I think, keeps Christopher in this quote unquote human condition is his unique knowledge that he has the ability to return to his home planet, regain his connection with his hierarchy and save his people. This is what keeps him from losing any sort of humanity throughout the movie, that knowledge that he can return to the fold with a grand success.

But for Vickis, there is no hope of return, there is no way for him to go back to his wife, go back to his job, his home and parents, as a result of not just his transformative state, but of his actions as well.

The vision that stands out to me from District 9 isn’t one just of racial segregation and rampant prejudice, but of the possibility that without a connection to society, mankind and perhaps all sentient beings are ultimately reduced to an animalistic, individualistic state. There is an indication at the end of the movie that Vickis still retains some of his humanity, but his transformation from mild-mannered office worker to a lightning-gun wielding, murderous freedom fighter taking joy out of his killings and looking out only for himself provides an interesting parallel to Christopher’s story. Without hope for a role in society, is the individual inevitably going to break free from societal constraints and, for better or for worse, become something alien?