Yasmine Arrington, a black Elon University senior, waited outside the Truitt Center on a chilly Jan. 21, 2015 night for E-Rides to pick her up.

She looked up, she said, and was confronted with two college-aged white males yelling racial and sexual slurs.

The alleged, unknown, perpetrators sped off — Arrington panicked. A blank face led to shock, then the shock gave way to tears.

“I couldn’t see them,” Arrington said. “I couldn’t run after them and take a photo of the license plate or the tag number. After they said what they said, I was in a state of shock.”

Arrington’s incident has not been the first racially-motivated incident at Elon in recent years — far from it. Since 2011, there have been more than five reported incidents of racial bias, many of them following similar patterns to the Jan. 21, 2015 incident. All have prompted frustration. Some have prompted a sense that change will never come.

To the victims of the crimes — most of which have resulted in no charges — racial bias at school is nothing new.

A group of white males in a convertible yelled the N-word in early September 2011 at a black student crossing North O’Kelly Avenue — right across the street from where Arrington said she was harassed — Elon University Police said at the time.

A male in a car at the light in front of McMichael allegedly shouted a homophobic slur at a student in early February, 2012.

A new bias and discrimination policy inclusive of all types of harassment was then presented to faculty and staff Feb. 13-14, 2012. Faculty voted on the policy unanimously in early March 2012, which was praised by many, including students.

Still, the incidents kept coming.

Two students, one black, one Jewish, found a swastika, the letters “KKK” and male genitalia drawn on a whiteboard outside of their Colonnades D dorm room in mid-September, 2013.

When Elon community members gathered to discuss the offenses, as they did after the latest one, administrators asked students how the university could better handle bias situations.

It was suggested that the school implement diversity education and anti-defamation courses into the Elon curriculum.

During Winter Term 2015, freshmen were asked to attend a four-hour Anti-Defamation League (ADL) Campus of Difference training session — to mixed reviews from attendees.

To junior Claire Lockard, who is white, the university is not doing an adequate job of discussing diversity.

“I believe [Elon] has systems in place that they hope or think will work, and they do try to make changes based on feedback that they’ve been given,” Lockard said. “But there’s something about the Elon Bubble that makes people feel like they can shout racial slurs and that that’s acceptable behavior within this community.”

Students seek solutions

One solution that a student offered to increase student engagement with diversity was the creation of a hands-on diversity training program. Such a program would be one option for satisfying an Experimental Learning Requirement (ELR).

Jamie Butler, the assistant director for Elon’s Center for Race, Ethnicity and Diversity Education (CREDE), believes that Elon needs to dig deeper and have more open, uncomfortable discussions.

“We are going to have to move away from some of the surface level [conversations],” Butler said. “Students don’t come to things [like the Jan. 26 forum] because we’ve already talked about this before. It’s time for us to give ourselves permission to go to the next level and not keep replaying the same conversations over and over again.”

In light of the low white student turnout at the Jan. 26 open forum, designed to discuss what happened to Ariington, Butler hoped that students, white and black, will do more to open what he sees as a stagnant campus conversation on race issues.

“The burden of the discussion can no longer be on individuals who identify in a marginalized group,” Butler said. “The burden of having these conversations has to be placed on the majority culture.”

Creating a discussion space

When people filed into the room Jan. 21, they were placed in one of 11 small discussion groups, but when the event started, the empty chairs stuck out like a sore thumb.

Randy Williams, dean of multicultural affairs, was particularly disappointed with the lack of white students in attendance.

“I would have loved to have seen a greater diversity of students,” Williams said. “To be quite frank, more white students [would have been nice]. We need to bring multiple people into the discussion.”

Although the forum didn’t generate the desired turnout, several people said the event was still worthwhile.

“I do think conversation matters,” Jackson said. “I thought there were some very good concrete suggestions [on how to address the incident and promote diversity].”

The event began with a series of three speeches with breaks in between for discussing questions that the speaker posed to the attendees.

Arrington delivered the first.

After she was done, she posed a straightforward question for the audience’s consideration: “What is it about Elon that makes these incidents OK?”

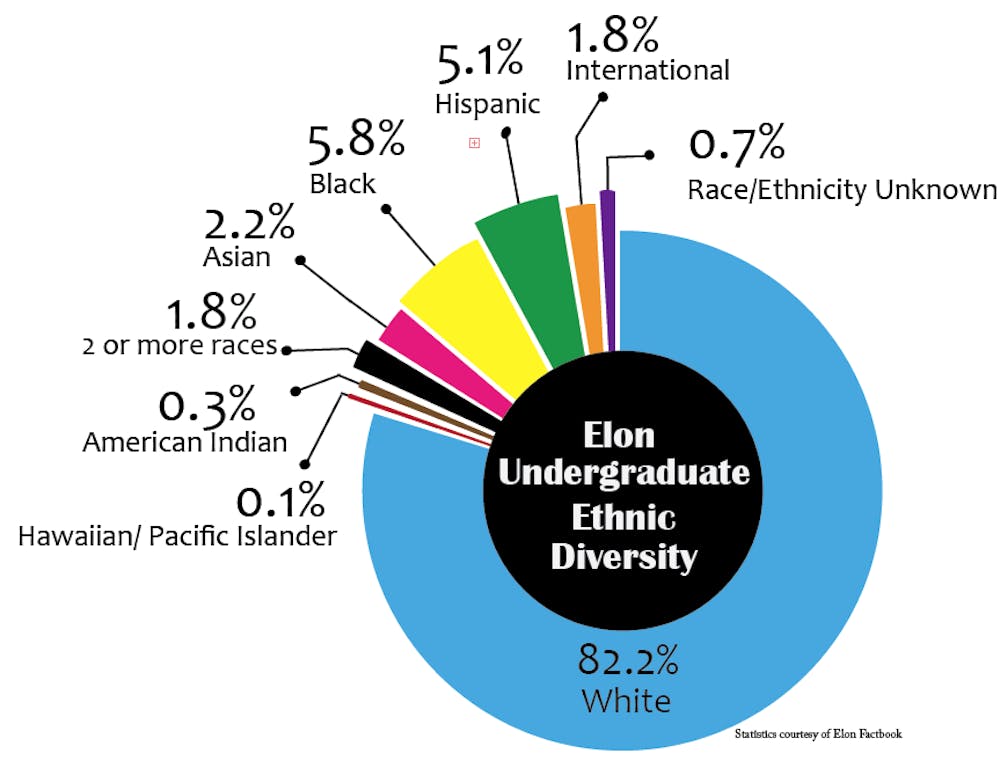

Several pointed to the lack of diversity on campus as one of the primary sources of the problem with on-campus racial biases. According to the Elon University 2014-15 Fact Book, 5.8 percent of Elon students are black, while an overwhelming 82.2 percent are white.

Seventeen percent of the Class of 2018 is defined as what is considered “ethnically diverse” — 2 percent black, 2 percent Asian, 6 percent Hispanic and 3 percent multiracial — according to the Admissions Class Profile webpage.

Strides made, with a ways to go

Butler said that diversity does, in a way, boil down to difference — and that’s OK.

“When I think of the word ‘diversity,’ I just think of differences in general,” Butler said. “Not only does it include racial and ethnic makeup, [but it also refers to] socioeconomic status, social orientation, geographical differences, upbringings and family structures. Anything that makes us unique and different, I would include in my definition of diversity.”

In the wake of the most recent racial bias incident, several students were angry because the perpetrators have yet to be identified after video footage examination. According to the Elon Campus Police incident report, the case is still under further investigation.

With the completion of the Inman Admission Center and future construction projects planned for an improved School of Communications, Arts West and Danieley Neighborhood, some attendees thought Elon should use its money toward upgrading its security cameras.

Arrington saw the footage and was disappointed that the perpetrators’ license plate or tag number could not be identified.

“Those cameras are horrible,” Arrington said. “I think we can update our cameras at least.”

Jackson believes that the existing security cameras, which are 10 years old, are suitable and capable of tagging vehicles.

“The university’s put a lot of cameras around that are relatively recent that have cut down on a lot of crime and violence on the campus,” Jackson said.

Steven House, provost and vice president for academic affairs, agrees with Jackson that the security cameras throughout campus perform well. Though the perpetrators haven’t been identified, House is confident in the ongoing investigation.

But the provost acknowledged a constant need for improvement, too.

“The university’s goal is to always take care of those individuals who have been targeted,” House said. “To create a campus climate that is always better than what we have [is important].”

During the open forum, a second speaker recalled an incident that occurred during his freshman year at Elon. After being called the “n-word,” he grabbed the person’s throat in response. He admitted he didn’t handle the situation appropriately, but he took physical action because he felt that the university would be of little service in disciplining the student who called him the “n-word.”

Aloud, he mused the use of reporting his story, thinking that nothing would have been done about it.

University administrators say otherwise, pointing to the depth of resources available, though many have only been created in recent years.

Elon’s Inclusive Community homepage includes a section on how to report incidents of bias, discrimination, harassment and hate.

Students have three options for filing such reports, which are anonymous, confidential and official. Safeline (336-278-3333), a confidential line for Elon community members, provides an immediate response by a dispatcher and then a call from a confidential advocate within 20 minutes.