Atypical day in Elon, North Carolina, might include the hustle and bustle of daily life going on as people rush around, absorbed in their busy schedules. Many sounds might be heard on this typical day: people talking, the wind through the leaves and the roar and scream of the train nearby. But we now know this is not a typical day in Elon. This is a typical Elon day in 1888, during the period of time in which a railroad depot was located in the town.

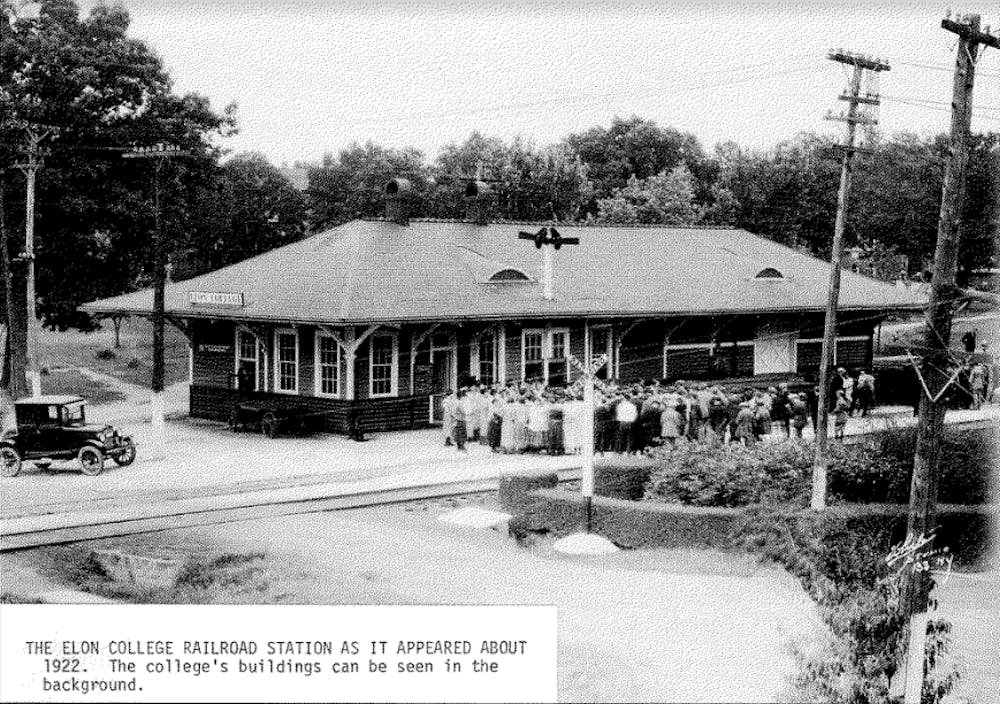

From the fall of 1887 until 1961, the railroad depot known as Mill Point served Elon in different ways. While at first it “was built to provide rail service to two textile mills,” according to Don Bolden’s book — “Images of America: Elon,” the station later “provided transportation to and from campus for generations of students,” according to a plaque on campus.

In the 58 years since the station’s closing, Elon University students have relied on alternate forms of transportation to get to and from campus over breaks, and faculty have often commuted upwards of an hour each way to get to and from work. This is something assistant professor of philosophy Ryan Johnson would like to change.

“Driving in traffic is bad for physical and mental health,” Johnson said. “As the saying goes, when you are in a car, everyone is your enemy.”

Commuting via train would alleviate this stress, Johnson said, especially as an increasing number of people live in towns like Greensboro, Durham and Raleigh.

“Making it easier for our staff members to get to/from campus by avoiding the worsening traffic seems like a great service to them,” Johnson wrote in an email.

The station would also provide “equity and justice” for students, according to Johnson.

“Some majors, such as education, require internships, which requires traveling off campus. But if one does not have a car, perhaps because a student does not come from a wealthier family, then such lower-income students are penalized,” Johnson said, adding that for international students who might come to Elon without driver’s licenses, “confining them to a car-dependent environment is akin to destining them to failure.”

Junior Liam Collins agrees that for students of lower-economic status, a train would be a benefit.

“Elon’s a pretty ritzy-ditzy rich kid space. A lot of kids’ parents are … from well-off places in the country,” Collins said. Students who are not as wealthy, Collins said, might be excluded.

“If [students] need an internship to graduate and they don’t have the means to complete an internship, they can’t go to Elon, you know, and that’s a problem,” Collins said. “Right off the bat if … we’re not giving them the means to complete those requirements, then we’re not doing our job as a university.”

A way for Elon to do its “job as a university” would be to “get other students’ foot in the door” and make it easier for students to commute, Collins said.

“We have a responsibility to leave Elon in a better place than when we found it in,” he said. “I think my contribution is to give opportunities to students like me who maybe otherwise wouldn’t have the opportunity to attend Elon.”

Johnson agrees that giving students new opportunities, among other things, would greatly improve the school, which he said is currently not up to par in terms of sustainability.

“Elon is promoting complete car-dependency, while still also calling itself a sustainable place. … We can put up as many compost bins as we want, but it will do nothing compared to the utter car-dependency that is [the] Elon campus,” Johnson said, emphasizing that “cars are terrible polluters.” But his dissatisfaction with cars, especially those used around Elon, does not end there.

“Most people drive to Elon, drive alone and in big cars,” Johnson said. “This is such a silly, privileged, entitled way to think about going through the world.”

Instead, Johnson said the use of a train at Elon is an obvious alternative, saying people at Elon and in similar places are bound by what he calls “car-slavery.”

“The hope is to show how wonderful and easy it is to use the train, and to make more converts from car-slavery to train-freedom, who will then spread the word further and further,” he said.

This “car-slavery,” according to Johnson, is also to blame for “the rise of obesity, the unbelievable environmental impact, the huge sway of oil companies, the 40,000 per year car-related deaths.” He even went so far as to say “the American highway system is rooted in Hitler’s plans for Nazi Germany.”

According to associate professor of German Scott Windham, “the connection between the Autobahn and the interstate highway system is too nebulous. ... There are other really good reasons to turn away from cars and toward mass transportation that have nothing to do with Nazism.”

In addition to accessibility and sustainability, Collins said a train station at Elon would significantly decrease the amount of isolation felt by many students who cannot get off campus.

“We talk so much about the Elon bubble, but we don’t really do much to pop it,” Collins said. “Elon’s a very interesting place because you’re here and it’s one place and you travel five minutes that way or five minutes in any direction, and it’s a completely different world. … I think that if we can introduce students to other ways of living, then that greatly opens up the global experience.”

The path to obtaining a train station will not be easy, Collins said, emphasizing that advocacy is the only realistic way to achieve the goal.

“Nothing happens on this campus unless students say they’re going to do it,” Collins said. “Reach out to your student government representatives … because they are the ones that are going to be able to advocate for that, and they can pass legislation that says this is something the student body wants. They can allocate money to be able to make it happen down the road.”

But Johnson said it might be easier to get a train station here than one might think.

“The cost will not be outlandish,” Johnson said, noting that the cost would be shared by multiple parties, including Elon University, the town of Elon, Norfolk-Southern, Amtrak and the North Carolina Department of Transportation.

The impact of a train station, no matter how expensive, would be worth it, according to Collins.

“Elon is going to be known as the town before Elon got the train station and after,” Collins said while reflecting on what, in his opinion, would be a massive change in Elon’s reputation and history.