When compared to statewide averages, Alamance County has higher rate of food insecurity, a lower median household income and more people without health insurance. The idea of fighting hunger, addiction and joblessness usually brings to mind shelters and soup kitchens, but Link Transit is providing a different kind of resource to address the county’s problems.

Link, which began in June 2016, is a public bus system with five fixed routes around Burlington, Gibsonville and Alamance Community College. Fare is $1 per ride or $4 for a day pass. Though Link's organizers said they are still ironing out the details of the new transit service, their aim is to address the common thread between many local issues: a lack of access — whether to food, medical care or retail centers.

The Need for Public Transportation

Alamance County has a history of failed industries. Its neighborhoods were built around the textile mills and the Western Electric Company plant, which employed many people throughout the 20th century. When those companies closed their doors for good in the 1980s and 1990s, some communities were left geographically isolated.

For many years, people who could not afford the high cost of owning a car had no way to get in and around downtown Burlington. Link Transit is meant to do exactly as its name suggests — link the area together so that all of the county’s residents, regardless of where they live or their economic background, can get where they need to go. So far, the response from the community has been positive.

“It has actually exceeded our expectations,” said Mike Nunn, director of transportation for the city of Burlington. “For our size and it being a new system, there were forecasts made, but you don’t know people. They make a choice every day to ride transit, so it started out strong, and it has continued strong.”

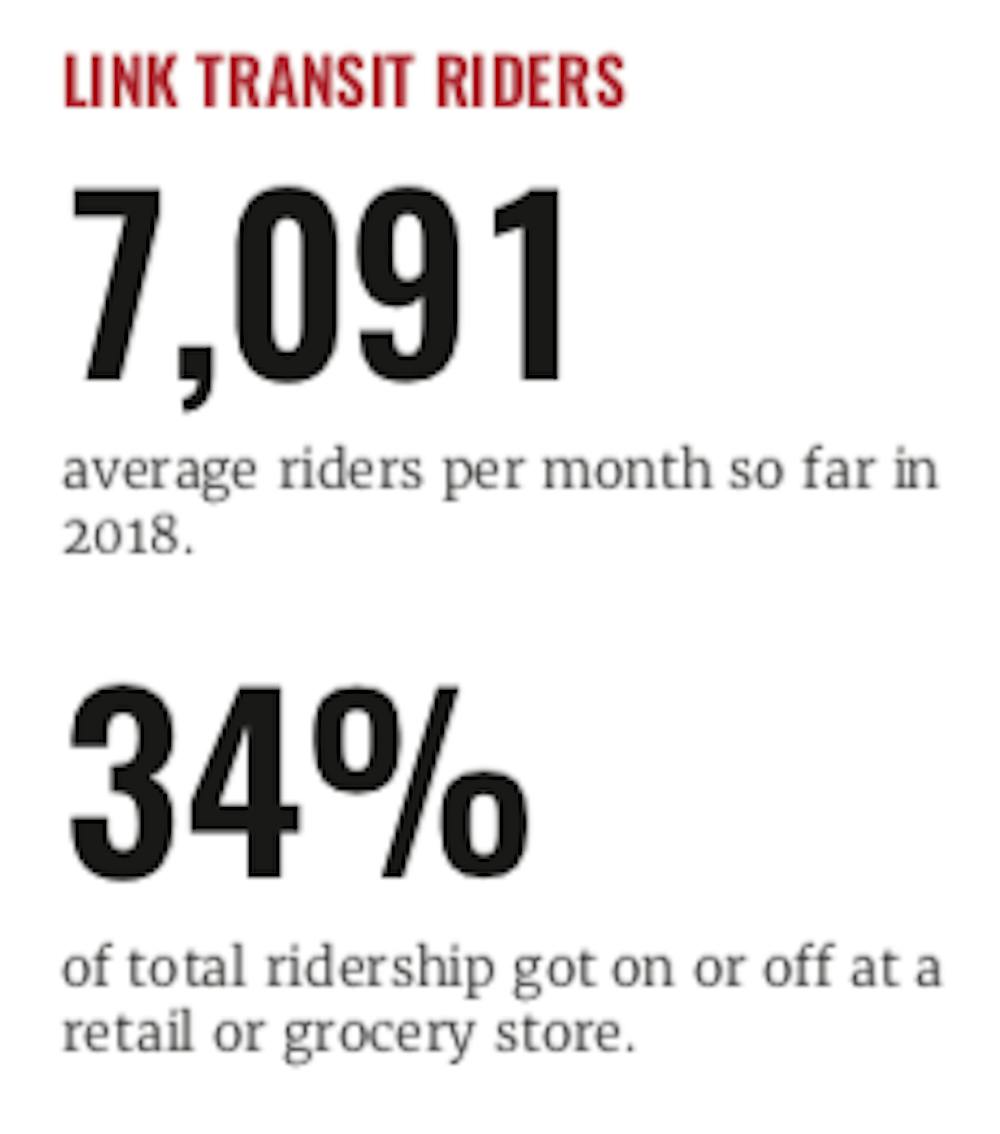

Link has averaged 7,091 riders per month so far in 2018, with August setting the new record for full-fare ridership at 8,122. Between April and June, 34 percent of total ridership got on or off at a retail or grocery store. The most popular stop was Holly Hill Mall on the blue and red routes, which saw a total of 2,152 riders during that time. Stops near centers for education and healthcare, such as Alamance Community College and Alamance Regional Medical, were the destinations of 19 percent of all riders.

Bumps in the Road

But Link has had its share of growing pains. One area of concern is the lack of bus stop shelters. Most stops consist of nothing more than a small sign, which can be difficult to find. At the blue route stop in Westbrook Shopping Center, that sign is on an otherwise ordinary pole in the middle of a large parking lot.

As Link entered its third year of operation last July, its hours of operation extended from 6:30 p.m. to 8 p.m., leading to an increase in daily ridership. Riders are also calling for a broader coverage area and for weekend service. There is also significant need for a reduced headway, or the time between buses at any given stop. Link’s current headway is around 90 minutes.

“I remember being involved in a lot of planning sessions before Link got started, and the wisdom of the professional planners seemed to be that you really don’t want to have a headway longer than 30 minutes,” said Bob Byrd, an Alamance County commissioner who sits on the transit system’s advisory commission.

Paying for Link

While these are all issues Link’s organizers are aware of, securing the funding required to address them remains a challenge. Link Transit is paid for in large part by a federal grant, which covers 80 percent of the system’s capital expenditures and 50 percent of its operational costs. But convincing other municipalities to add the additional expense to their budget is an obstacle to expanding the system’s geography.

The orange route currently makes three stops in Graham, but the Graham City Council’s decision not to provide funding for the program means that government buildings such as the county seat, jail and courthouse are more accessible via Link for people who live in Burlington than for many residents of Graham itself, where those buildings are located.

“To me, that is unfortunate because you’re leaving it to a municipality to provide a barrier to the rest of the community from receiving really important services,” said Byrd. “I remember going to those public meetings where they were debating whether or not to participate in Link Transit, and it was so ugly. There were people coming up and begging to have the service because they need it for work.”

For government officials in Graham, the costs of operating a full route in the city beyond the three existing stops outweighed the benefits.

"We believed that the Link Transit was not going to benefit the citizens of Graham," said Graham Mayor Jerry Peterman. "Our participation would allow us to have one more stop and one member of their board ... After watching the buses traveling around Graham, I still believe we did the right thing. Although the Link figures say a different number, I never see more than one or two people riding the Graham route, and usually it’s only the driver."

Adding more buses, more stops and more hours comes with an obvious increase in cost. While it is difficult to persuade some taxpayers to pay for a service they would not use, Byrd pointed out that their tax dollars are already subsidizing people in private vehicles by paying for roads. On top of that, the federal grant that Link relies on is calculated based on the population of the entire area, but only Burlington and Gibsonville are taking advantage of it.

“For all the communities really in the urban system, Graham, Burlington — the cities — their populations are helping us in that grant formula. To some, it would make sense to say let’s use that, even though we’re going to have a new expense,” Nunn said. “There’s a lot of discussion about the benefit of transit, but then it’s somewhat down to a dollar-for-dollar comparison, and that will never really shake out. Transit is a public service. It’s not a business.”