Though Elon University’s environmental initiatives have earned it praise from a number of its stakeholders, its rapid expansion has encroached on some of its sustainability objectives and challenged it to find ways to reduce emissions as the campus expands and enrollment rises.

Between 2008 — the baseline year for carbon emission measurements — and 2014, Elon added about 670,000 square feet and about 850 students to its campus. It succeeded in shrinking certain aspects of its carbon footprint during that seven-year period, but its growth has outpaced its overall rate of emissions reductions and highlighted the conflict that can sometimes exist between sustainable development and building aesthetics.

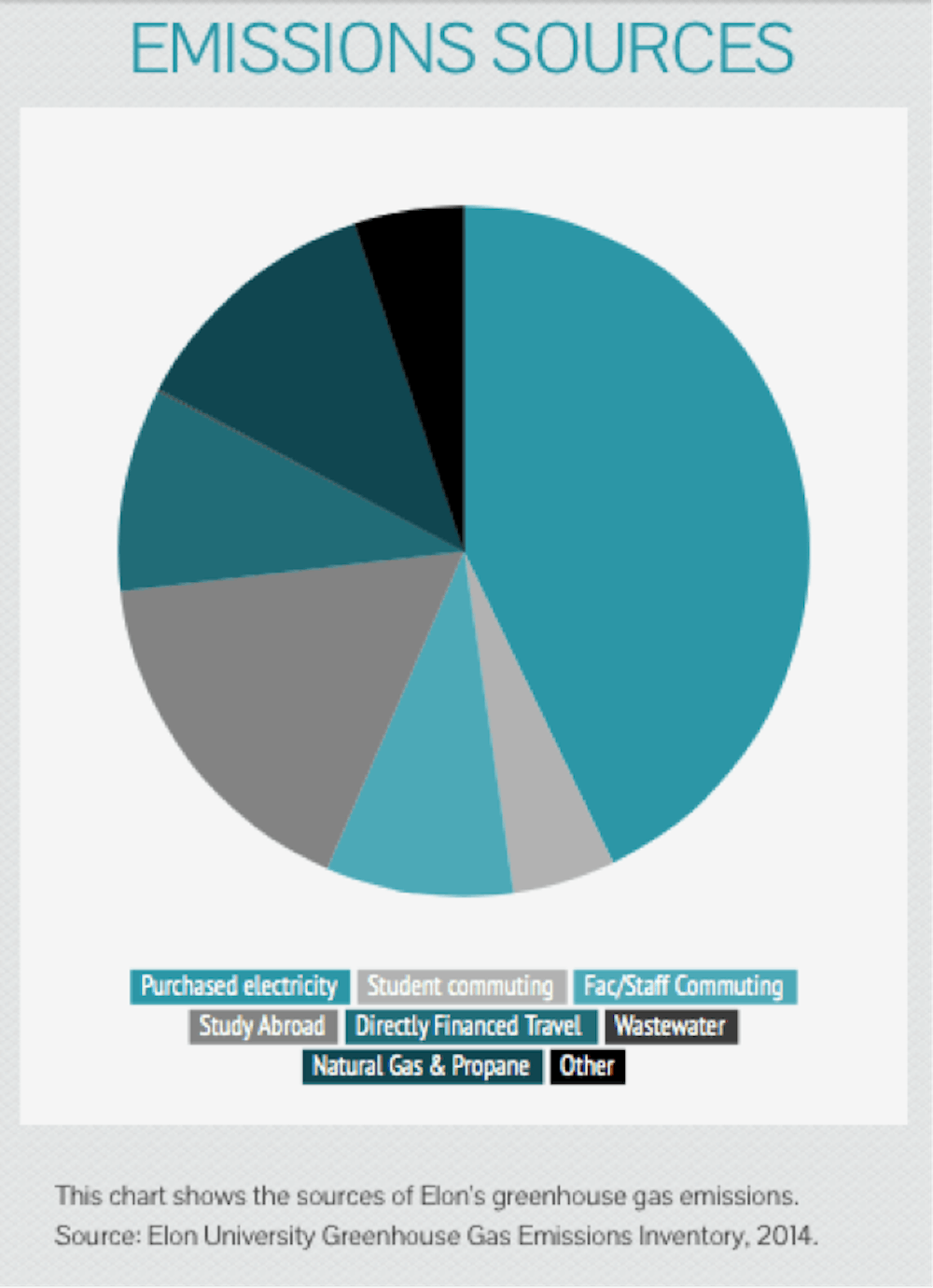

During the measurement period, Elon’s carbon emissions increased by more than 10 percent, according to the school’s most recent greenhouse gas inventory. The university is not on track to reduce net carbon emissions by 5 percent this year, an interim goal set five years ago in the university’s Climate Action Plan.

“In terms of sustainability, a challenge today and in the future is changing behaviors,” Elaine Durr, director of sustainability, said in an email. “Another sustainability challenge in terms of resources — personnel, time, financial — is staying current on the most effective and efficient technologies that will help reduce emissions.”

Between 2008 and 2014, emissions per student decreased by 4.6 percent, and emissions per 1,000 square feet of building space decreased by 18 percent. But building energy usage increased slightly between 2013 and 2014, when the school added 185,145 square feet to its campus.

“I think it’s just catching up with us that we added more square footage than people coming in, and now we’ve hired more faculty and staff here and they all use all kinds of energy,” said Robert Buchholz, associate vice president for facilities management and director of Physical Plant.

Despite the 4.6 percent reduction during the measurement period, energy usage per student has been growing steadily since 2011, in part because the university has built more on-campus housing, Buchholz said.

“If you’re bringing students back in to live on campus, then you’re going to see an increase in the amount of electricity used,” he said.

Elon’s commitment to the environment developed in earnest in 2006-2007 academic year, when it developed a sustainability master plan that set an overarching goal to achieve carbon neutrality within 30 years and recommended a long list of other green initiatives.

“It is truly fabulous,” said Robert Charest, an associate professor of environmental studies at Elon who teaches sustainable design and architecture. “To have a department devoted to sustainability is truly remarkable at a small university, and it really feels like a priority.”

Since 2008, Elon has made strides in achieving a number of the goals outlined in the plan. It has expanded its recycling and composting programs and installed a geothermal system for five residential buildings and solar thermal water heating systems for five buildings on campus.

The university has also created more opportunities for faculty, staff and students to learn about and teach sustainable practices through classes and programs. And it is now working with New Jersey-based Suntuity to build a 15-acre expanse of solar panels near Loy Farm, where many of Elon’s sustainable agriculture and design classes are taught.

“The nice thing about having Loy Farm here is that we’ve managed to get the university’s blessing to bring together two of the most challenging phenomena for the world, which are agriculture and food production and land use for building structures,” Charest said.

In February, Elon shared its most recent sustainability data with the Princeton Review and the Sierra Club, organizations that factor eco-friendliness into their university rankings. In the fall of 2015, the university plans to share the information with the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS), a program of the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education that rates universities based on self-reported data related to environmental, social and economic components of sustainability.

When Elon last submitted a STARS report in February 2014, the university earned a Silver rating. It scored relatively highly in the “Education & Research” and “Planning, Administration & Engagement” categories.

But it earned less than 50 percent of the points available in the building, climate and energy subsets of the “Operations” category, which took into account how much the institution had reduced its emissions and building energy usage from a 2005 baseline, as well the LEED certifications it had obtained for new and existing buildings.

The LEED certification system, developed by the U.S. Green Building Council, scores buildings on site sustainability, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources and indoor environmental quality. A building may achieve certified, silver, gold or platinum ratings depending on the number of points it earns, and the cost of certification depends on the size of the project.

According to the most recent data from February 2015, the university added more than 34,500 square feet of LEED Gold certified space since the publication of the 2014 STARS report. But certification does not necessarily take into account the many variables that could affect a structure’s sustainability during and after its construction, Charest said.

“There has to be framework, and LEED is a good framework, but I think that it’s a system that is based way too much on honor,” Charest said. “The commissioning agency that oversees it doesn’t have a really strong presence, as least it’s not required by LEED standards.”

More than half of the university’s LEED-eligible space has achieved certification, but the certified areas constitute only about 500,000 of 2,590,000 square feet of total building space on campus. Because the university has not pursued LEED certification for existing buildings, it earned less than three of the seven points available in the STARS buildings operation and maintenance category.

Buchholz said the money it would cost to certify existing buildings might be better spent on other sustainability projects. He is working to develop a system that can track the use of electricity, water and gas throughout campus, as well as a dashboard that would allow him to manage the amounts from a central location.

“I hope to spend money on that, and not on LEED certification (for existing buildings),” Buchholz said. “It’s a matter of what you think. There are things you can do now in the STARS report, and things you can target later on and hopefully pick up more and more points.”

Buchholz said he hopes the university will include the system, which could be developed and installed for less than $700,000, in its next budget and fund it over a three-year period.

“Everyone wants to be able to meter things, so the prices of the meters are coming down and the prices of the systems are coming down,” he said. “Stuff like that will help us do better and get our energy usage down.”

Despite the fact that most of Elon’s new buildings are LEED certified, Charest said he thinks the university might have missed an opportunity to teach students about sustainable architecture when it decided to model many of them on existing campus buildings with brick veneer and fiberglass columns.

“We still have to stop building buildings that are built in 2015 but look like they’re built in 1887,” he said. “Buildings, in one way or another, should be edifying tools part of the learning environment, especially at a college, and that just doesn’t happen here. The impression we’re left with is on this kind of homogenous campus, if you fly through really quickly, is that all of the buildings look like they were built at the inception of the university, but that is really fake.”

And some of the newer designs, though constructed in adherence with LEED standards, have aesthetic components that decrease their overall energy efficiency.

The high ceilings in the great hall in the new Global Commons building make it more difficult to heat efficiently, Buchholz said.

“There are things you can do, but still, you’re heating space that nobody is using,” he said. “Ceiling fans can push the heat back down, but you’re not going to get it down to the energy per square foot (of a smaller room).”