The last two weeks have been filled with bizarre events in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions. An earthquake centered in Virginia sent hanging lights swaying and leaves shaking from North Carolina to New York. Then, Hurricane Irene worked its way up the East Coast, causing torrential rain and wind, leaving flooding and power outages across at least 11 states and even taking a few lives. Irene also spawned several tornadoes in locations that rarely, if ever, see that type of weather, like the Outer Banks of North Carolina and coastal Delaware.

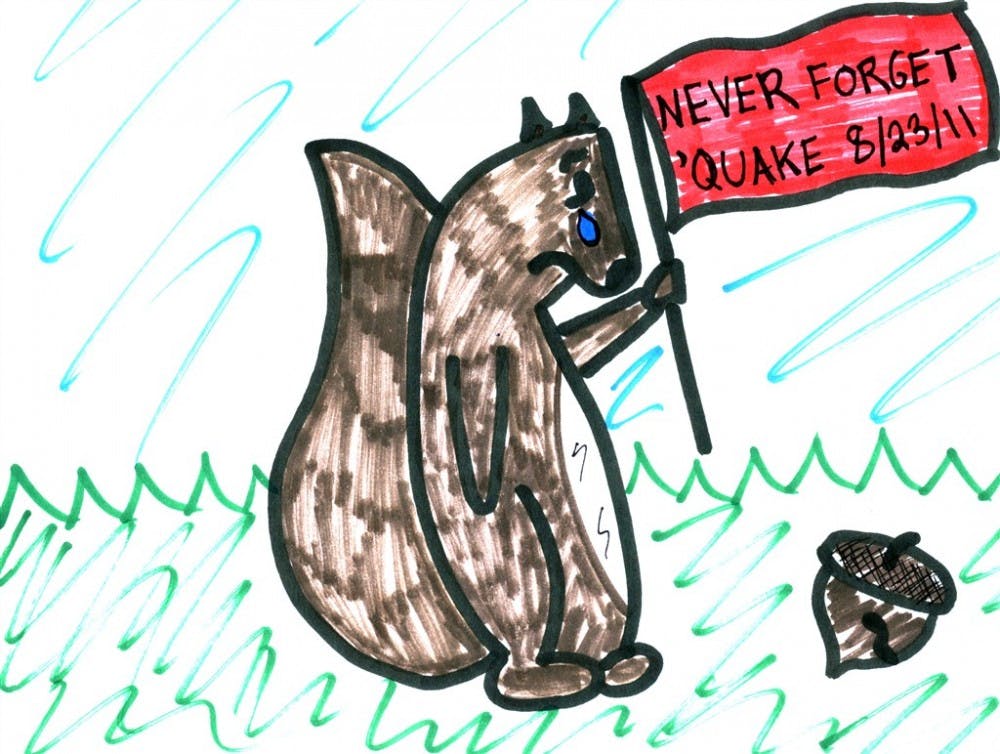

While some have treated these occurrences with due seriousness, others have seen an opportunity to have a few laughs, create a funny Facebook status or come up with an excuse not to do something (i.e. "We can't go to the store, it's hurricane-ing!")

But those who had statuses like "Survived the earthquake!" or "Irene's all gone, guess we have class Monday" would do well to remember back to March, when an 8.9-magnitude earthquake and resulting tsunami killed more than 16,000 people in Japan, or back to August 2005, when Hurricane Katrina killed 1,836 people. Both cases caused billions of dollars in damages and inflicted immeasurable amounts of emotional trauma.

Those affected by the recent events here in the United States should count themselves lucky that the U.S's recovery from Hurricane Irene will take weeks or months, not years, and that the worst thing to deal with from the earthquake was a group of tourists inconvenienced by the temporary closure of the Washington Monument.

This past weekend, several news networks devoted round-the-clock coverage to nothing but the hurricane, probably much to the annoyance of the rest of the country. They used the words "crisis" and "disaster" to describe the weather. During the earthquake, "panic" and "pandemonium" were common terms used by the news media.

Both of these events beg the question, when does a situation go from bad or troubling to a crisis or disaster? And when does a surprising event with confused participants and onlookers become panic or pandemonium?

When does the burden of defining an event shift from the participants of an event to the media? Does it ever actually belong to those directly impacted?

By naming an event a "disaster" or a "tragedy," a stigma and a perception is created. It's like telling somebody they are going to get a headache. If the person is told that, he or she is far more likely to feel that headache, even though it may be completely made up.

Is this sensationalizing about ratings, readership or pandering to an audience that thrives on watching footage or seeing pictures of buildings being washed away or roofs being torn off houses? It is unclear when "just the facts" became "just the facts and whatever title we decide to assign to this event." It is also unclear where the vicious cycle of using disasters as fodder for conversation and late-night television monologues began and if the trend can be stopped.

Hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes and other natural disasters aren't material for jokes puns or clever tweets. They're dangerous and can be life-threatening and should be discussed with respect and reverence by all.