“No, where are you really from?”

It’s a question sophomore Mackenzie Martinez hears a lot. She responds with the truth. She’s from Richmond, Virginia. But because of her brown skin and black hair, she encounters a lot of people who are looking for a different answer.

Martinez’ ancestral background makes her much more diverse than meets the eye. Her dad is half Mexican and half French Canadian and her mom is Jewish. So when someone acts surprised that she’s “from” Richmond and not somewhere more exotic, she says it’s a comment that cuts deep.

“It’s undermining who you are,” Martinez said. “It's dehumanizing in a lot of ways. Because I'm a human being, I'm a friend, I'm a sister, I'm a student, I'm all these things. But at the end of the day, what so many people only see is I'm Hispanic, I'm ethnic, I'm different, I'm not your norm. And that's all they see.”

And that’s not the only question she has to deal with. Her days are strewn with comments that aren’t intentionally harmful, but still make pernicious assumptions about who she is.

“In every Spanish class I've ever been in,” Martinez said, “someone has made a comment to me within the first week of school about my ethnicity. Like, ‘Oh, don't you speak Mexican at home?’”

She recalled one instance from earlier this semester. On the first day of Spanish class, an acquaintance took the desk next to her and said that she always likes sitting next to a fluent speaker. Martinez, whose half-Mexican father didn’t even grow up speaking Spanish, doesn’t consider herself fluent.

“I’m not fluent, I’m just brown,” she explained to the classmate in a retort that was met with nervous laughter.

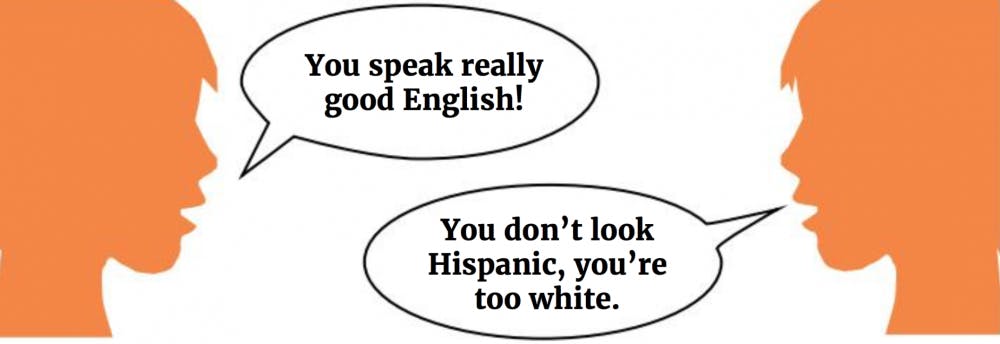

These types of comments and questions – the offhand remarks and the unknowingly ignorant assumptions – they all fall into the category of “microaggression.”

In fact, microaggressions are, by definition, subtle, indirect or unintentional. They’re the day-to-day behaviors and comments that communicate derogatory or prejudiced attitudes toward a member of a marginalized group or minority.

“It's nothing as extreme as police brutality or anything,” Martinez said. “It's not like that kind of inequality or discrimination, but it's just enough that it gets under your skin and just kind of stays with you for a long time.”

Because they can be so subtle and unintentional, Latino students reported experiencing microaggressions fairly regularly.

Christina Gallegos said she’s no stranger to that “where are you really from” question. She’s heard it from another student at a party, from a random passerby walking his dog.

“Especially for Latino / Hispanic people,” Gallegos said, “they’re all just labeled as immigrants, not accounting for the fact that a lot of them were actually born here. And even though like our parents are immigrants, we're Americans, we are more American than we are Hispanic."

Those types of questions, she says, contribute to the alienation of non-white people in America, while those with European ancestry never have to explain their backgrounds.

“It’s just funny,” Gallegos said, “because they don't ask themselves, ‘Where are you from, what is your European ethnicity or where did your grandparents come from?’ I feel like white people have some damn nerves to be asking people where they’re from when their grandparents are immigrants as well.”

While the comments often fall short of being blatant racism or intentional acts of hostility, they still make those on the receiving end feel uncomfortable and marginalized. Senior Lily Sobalvarro says that people shouldn’t have to understand the full complexity of microaggressions to understand why they should stop saying them.

“It's easy for people to dismiss microaggressions and say that we're being too sensitive, or she was just curious, or it was meant as a harmless question,” Sobalvarro said. “At the end of the day it's all intention versus impact. While your intentions may be good, the impact that it has on other people should ultimately outweigh your intentions. You could have the best intentions in the world, but if it's causing harm then you should stop.”