On Jan. 9, 2018, the federal district court ruled against the North Carolina legislature’s motion to redraw 13 congressional districts. This is the first time that the federal court has ruled against gerrymandering on a partisan basis. Jessica Carew, assistant professor of political science, explains the federal district court’s decision to redraw the North Carolina congressional map.

Q: What is gerrymandering?

A: Gerrymandering is the means by which individuals who are able to influence the size of districts...draw districts that are for the purpose of political representation. In a way that will benefit them the most, and more specifically, their political party...Gerrymandering goes all the way back to the beginning of our nation.

Elbridge Gerry was the first who hinged on a district of which people thought was in the shape of a salamander, which is how we get this idea of gerrymandering. It is something that has traditionally been used to gain political power and that is what we’re seeing right now.

Q: Why is gerrymandering a problem?

A: You would think that it wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing. You put people in a position where you know they are eventually going to have that power to redraw these lines. However, the real problem comes in because it decreases the degree to which we can actually suggest that we have the ability to get representatives who are willing to represent us. It’s this idea that the representatives are choosing their constituents, rather than the constituents getting to choose their representatives. Especially given the types of technology that we have that allows us to pull these voter lists with their addresses, and very surgically draw certain neighborhoods or houses out of particular districts.

We know that both political parties have used this particular tactic. We have heard a lot in the news lately, in terms of the GOP and how gerrymandering is used on the people, and we also know that various democratic politicians have used it in New York. At one point, someone was drawn out of his own district by his party so he would not be able to run for that office. Again, gerrymandering is the moving-over of one community, in terms of drawing them out of it.

Q: Why did the federal district court order the North Carolina congressional districts to be redrawn?

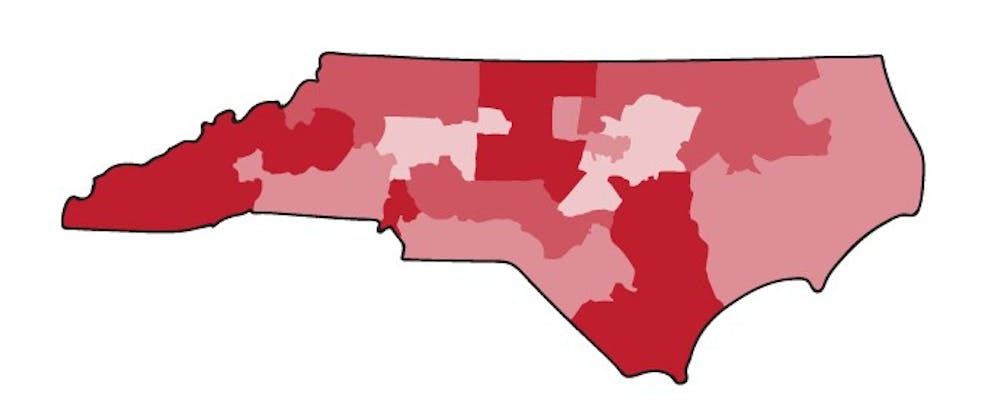

A: They ended up having to do this because of the specific way in which the General Assembly, and more directly the North Carolina state legislature, had very purposefully decided to redraw lines in a way that was not just based on party, but based on issues concerning race. We have all of this access to technology in order to be able to communicate with one another, but what that then does is that we do leave a little bit of a breadcrumb trail if people ever come looking to see what happened.

The courts were able to find evidence of various state legislators asking for information, concerning where African-Americans lived and how they voted. They were able to use that information in order to try to tailor the new laws that they were putting in place. Both in terms of gerrymandering and of decreasing the number of days for early voting, and to cut out the ability of people to have ‘Souls to the Polls’ — drives where people can have service in the morning on Sunday and then encourage people to vote in the afternoon.

The courts found that it is a concept of a surgical precision, in terms of drawing out exactly how it is that particularly African-Americans participate, and working to ensure that that would not be much of a viable situation for them.

Q: What is the importance of the court’s ruling of gerrymandering on a partisan basis?

A: This is the first time that the courts are saying it’s unconstitutional to work to give a particular party an unfair advantage; to make it so even though one party has a majority, but the party in the minority actually did get into office. The minority was able to set in stone its ability to continue to get re-elected, even though that is not what the majority of the votes suggest. It’s a big deal because this is going to have a huge bearing on the vast majority of the states, with regards to how they go about actually drawing their lines when they redistrict every ten years. We have a census with population information, and then we redistrict.

The reason that it matters is because the vast majority of states have systems for redistricting that allows for state legislatures to redraw the lines. It’s the party in power that gets to redraw the lines. Once those parties come in every ten years, it’s the individuals who actually get to redraw those lines. This particular ruling is calling some of that into question, by a way of indicating that they are not going to be allowed to take party into account in the ways that they have been in the past.

This is great news for some of those activist groups out there that have been working on this for a very long time, where they would like to have impartial or nonpartisan panels that are appointed to actually do this work, so that you can create districts that are representative more broadly, rather than just in terms of the interests of a particular politician or party.

Q: How will the ruling affect the future of competitive elections?

A: The ruling suggests that it will actually make them more competitive. You want to have competitive elections because you want to have many voices in the ring so that you don’t just have the exact same people representing a diverse group of people.

If you can have that competition, those individuals will – even if they don’t get the person in office that they want – indicate that it was a close election last time, so maybe you do need to start paying attention to what our interests are so that you can get back into office because we’re pushing you, electorally.