In a dimly lit green room in the back of Elon University’s McCrary Theatre, artist, spoken word performer and filmmaker Kip Fulbeck described a vivid memory from his childhood.

“I remember a girl in fifth grade saying, ‘I know you like me. Why would I like you? You’re brown,’” Fulbeck said.

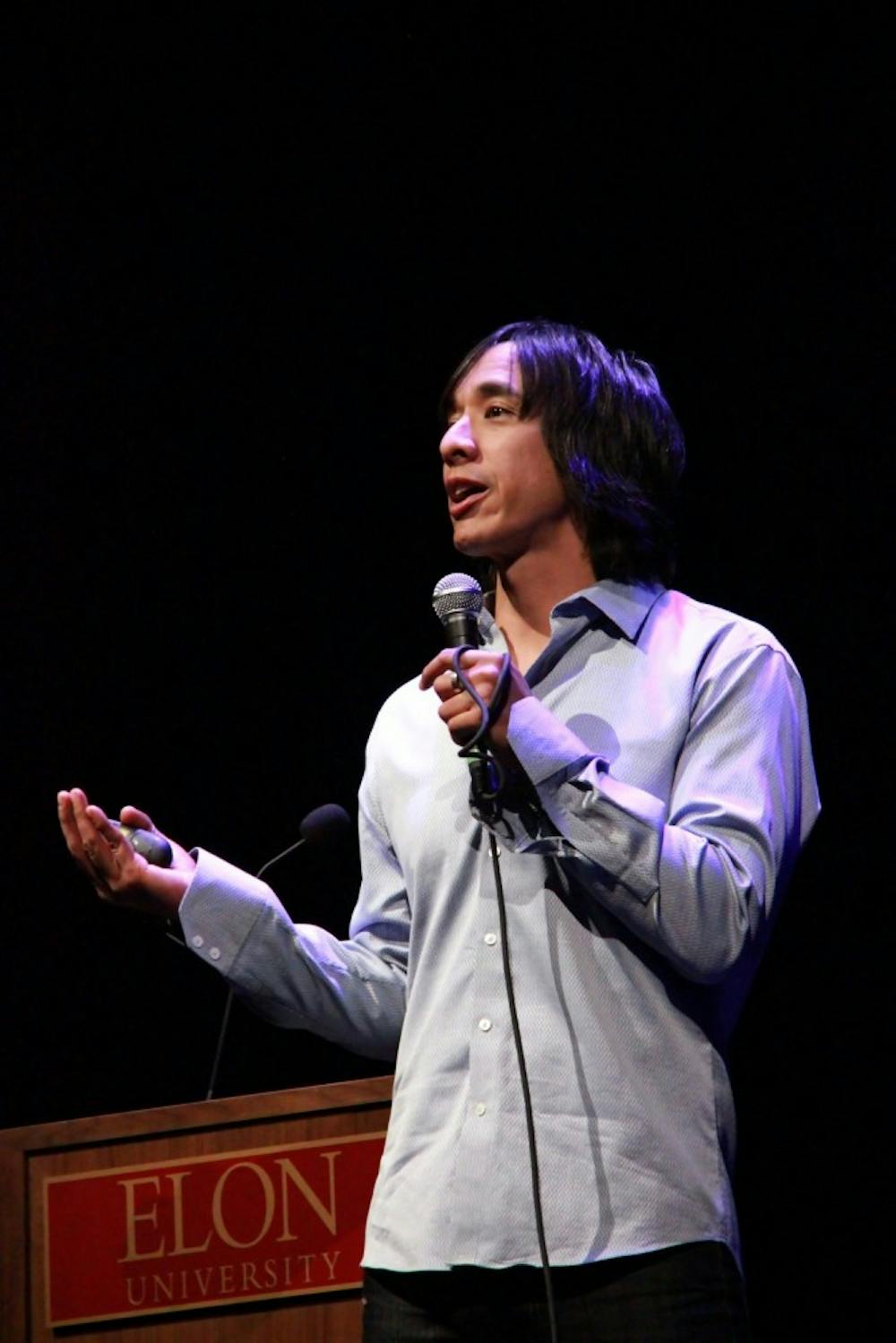

It is this side of Fulbeck that the audience glimpsed when he performed “Race, Sex and Tattoos” Jan. 15, part of the 2015 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Beloved Community Celebration event series.

Fulbeck explored the contemporary United States’ role in celebrating diversity through the spoken word and other media.

“I think every kid doesn’t feel accepted for some ways, you know,” Fulbeck said. “It could be for economics, it could be for physical stature, whatever it is. But certainly race and ethnicity played a big role for me.”

The 49-year-old grew up in a time when his parents’ interracial marriage was considered illegal in many states. It was only in 1967 that the Supreme Court overturned laws prohibiting such unions.

“My family is full-blooded Chinese from China, so I grew up as the white kid at home,” he said. “I was the kid who didn’t get the language, like the food. … Then I go to school, and I’m like the Asian kid at school, and they’re like, ‘Let’s put the Chinese kid in the trashcan, yeah!’”

From these pieces, Fulbeck channeled his questions and thoughts about identity into the Hapa Project. Photographs of more than 1,200 volunteers laid the foundation.

“[Hapa is] a Hawaiian word for ‘half,’ and I first heard it when I was three or four years old in California,” Fulbeck said. “When I was a kid I thought it just meant Asian-white, because that’s what I knew.”

Beginning in 2001, Fulbeck photographed thousands of volunteers who self-identified as Hapa, someone with mixed ethnic heritage with partial roots in Asian and/or Pacific Islander ancestry.

He photographed every person the same way: bare skin from the shoulders up, natural expression and minimal makeup.

After taking the photos, Fulbeck posed a simple question: “What are you?”

The results were greater than he ever imagined.

“I would do a shoot in San Francisco and get there at 6 o’clock for a 7 o’clock shoot, and there would be 45 people waiting outside,” Fulbeck said. “I think when people have lived in a time where no one is telling your story, no one is acknowledging your existence, and you’re given an opportunity to say something, you’re like, ‘Oh, I’ve got something to say.’”

Fulbeck has since transformed these pictures and written statements into an exhibition that has been showcased in museums across the nation. People passing through have the opportunity to take a picture of themselves and compose a written statement. The idle museumgoers become active participants in creating art and celebrating identity. In one museum, the walls were filled with pictures after a mere four hours.

“I was hoping [the walls] would fill up in four months [with pictures],” Fulbeck said. “That was my goal. I had no idea it would fill up like that. I’ve always been surprised by how many people will gravitate toward my projects,” Fulbeck said.

Fulbeck is no stranger to holding the attention of a room. When he isn’t creating collections, Fulbeck teaches for the University of California at Santa Barbara. He established high standards for those who enroll in his classes.

“I hope that they leave more conscious. I drop them if they don’t,” he said. “They have to be aware of what’s around them. I want them to understand their place and pick their battles, especially the politically active ones.”

Fulbeck extended the same expectations to his children. Upon the completion of his tour, Fulbeck’s immediate future plans are to be a dad to his two children for a while and to take a break from constantly working and traveling for his pieces.

As for the girl in fifth grade who didn’t like him, she seems to have moved on.

“The hardest part for me is looking back, and it wasn’t that she said that,” Fulbeck said. “I mean, we’re friends on Facebook now. The problem was that in my head I was like, ‘Oh yeah, that makes total sense, why would you like me?’ It’s that acceptance and the self-hate — that’s the hard part. That’s the reason I do this work with people, to explore their own identities, their own words.”