For Jessica Mahon, getting a master’s degree went hand in hand with becoming a teacher. But Mahon is from New York, where a master’s degree is required for public school teachers to become fully certified. Now, in her sixth year at Newland Elementary School in Burlington, her master’s degree is considered extraneous.

Mahon is lucky. She graduated from Elon University’s Master’s of Education program before the North Carolina legislature instituted a series of cuts and adjustments to the state’s public education system. Others have felt the effects more, and Mahon has seen this firsthand.

“I know probably half a dozen or a dozen people who are looking to leave,” she said. “Some are looking to go back north. Some have gone to Virginia and Michigan.”

Sweeping changes to the North Carolina education system passed by the General Assembly in July 2013 dealt another blow to teacher salaries by eliminating pay raises for teachers with advanced degrees.

Before the new legislation took effect in December 2013, teachers with master’s degrees could earn about 10 percent more than teachers with only a bachelor’s degree.

North Carolina’s stingy salary for teachers has been discouraging even with her master’s pay raise, Mahon said.

“As a teacher here, it feels like they don’t value what we’re doing,” she said. “It sends the wrong message to everyone who’s been here working hard.”

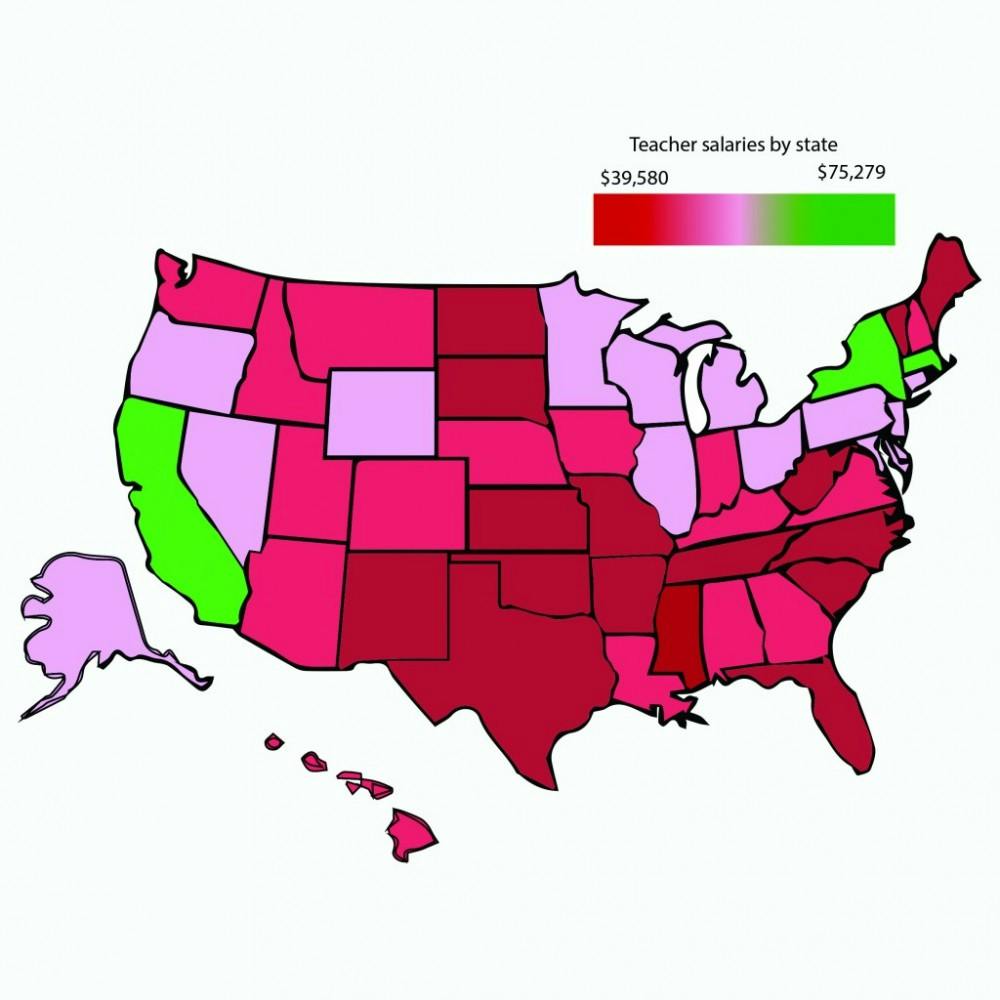

New York’s teaching climate differs exponentially from North Carolina’s. New York teachers have the highest salaries in the nation. North Carolina ranks 46th in teacher salary and 48th in new teacher salary.

The average salary for North Carolina teachers in 2013 was $45,737 — 20.8 percent less than the national average of $56,383.

Elimination of pay raises for teachers with master’s degrees took effect when more people than ever were pursuing advanced degrees. According to the United States Census Bureau, in the field of education, the number of people who have sought out master’s degrees has increased by 75.3 percent from 1990 to 2009.

A recent study by the Pew Research Center indicated that, as a whole, Millennials with advanced degrees earn more than those with bachelor’s degrees. The average earnings of those with master’s degrees are on the rise across most professions. The average monthly income of 25-to 34-year-olds with master’s degrees rose 23 percent from 1984 to 2009.

These data are reflected in Elon University’s graduate school admission rates. From 2004 to 2013, the number of students who applied for a graduate program at Elon increased by 1,724 students.

Adapting to decreased enrollment

While there has been an increase in admission rates, enrollment trends in Elon’s Master’s of Education (M. Ed.) department do not follow the form of other Elon graduate programs. Enrollment has declined since 2008, dropping by 34 percent since then.

The program began in 2001 with eight students. In 2007, with the induction of a new gifted education program, Elon’s M. Ed. program spiked, enrolling 50 students. But since the economy took a turn in 2008, program numbers have been in freefall. A slight increase in enrollment in 2013 has given Angela Owusu-Ansah, associate dean of the School of Education, a glimpse of hope.

As the North Carolina legislature has continued to whittle away at teacher salaries, Owusu-Ansah and the Elon education faculty have done their best to adapt the Master’s of Education program to the changing status of education in the state.

When Owusu-Ansah was hired in 2011, the M. Ed program had 22 students. She guided the program through a series of additions, which involved two primary components.

The first, study abroad, directly aligns with Elon’s goal of producing global citizens. M. Ed students now have the option of spending time in Costa Rica learning about diverse curricula and teaching methods, or

taking an additional class at Elon.

“We go to Costa Rica with service in mind,” Owusu-Ansah said. “But we leave with more knowledge and experience working with Hispanic children.”

Studying abroad, Owusu-Ansah said, is a crucial aspect of educating students about evolving classroom demographics.

A 2011 study by the Pew Research Center ranked North Carolina 11th in the nation in total Hispanic population and 12th in the number of Hispanics enrolled in public school. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in North Carolina, one in three children nationwide is from a minority group. A $1,000 increase in tuition costs accompanied this addition to the M. Ed. program.

“With the study abroad piece, we’ve calculated what the bare minimum cost was and added it to the tuition,” Owusu-Ansah said. “Everybody is trying to figure out a way to make it more relevant for teachers and more doable.”

That was also the goal when the M. Ed. program included National Board Certification for Professional Teaching Standards in the curriculum. One way teachers can still increase their pay scale, even after the removal of advanced degree pay raises, is to become National Board-certified. Teachers who have earned their National Board certification earn 12 percent more than those who have not.

“We’re trying to meet teachers where they are,” Owusu-Ansah said. “When you get National Board certified, wherever you were trained, it standardizes you.”

These decisions were made based on the results of data accumulated from surveying three North Carolina counties.

“We found out from the people we plan to serve what they wanted,” Owusu-Ansah said. “The easiest fix was study abroad and National Board certification.”

From evolution to endangerment

Even after adapting the program to fit the needs of today’s teachers, enrollment numbers for the 2014 cohort are expected to be low.

“The drop is huge,” Owusu-Ansah said. “It’s because of all this [legislation]. Some can’t afford it because they won’t get it back in their salary.”

The reality of a career in education has set in for many, and teachers have realized they can’t afford to be ambitious.

“You venture into doing graduate studies and advanced studies when you’re in a good place and looking to build your self-esteem and such,” she said. “But when you’re just in survival mode, it’s the last thing on your mind.”

Now, with the removal of teacher tenure, growing class sizes and reduced numbers of teaching assistants — in addition to cancelling pay raises for teachers with advanced degrees — teaching jobs are more demanding. Teachers, who are spread more thinly than ever, have even less time to pursue an advanced degree because their jobs require more out of them.

Given the immediacy with which the legislation took effect, students in the pipeline of Elon’s M. Ed. program completed an accelerated year to avoid losing the monetary benefits of their degrees.

“It’s disheartening,” Owusu-Ansah said. “And teachers haven’t had a raise in so many years. It shows that the efforts and hard work are not appreciated.”

Underappreciated and underpaid

Nicole Valenti, a graduate of Elon’s M. Ed. program and teacher at Newland Elementary School in Burlington, said leaving North Carolina would mean uprooting from her home of 15 years. Valenti completed her undergraduate degree at Elon and began teaching at Newland Elementary School soon after. With several years of teaching experience under her belt, she applied to graduate school.

But, Valenti said, the field of education and teaching as a profession is devalued and, at times, disrespected, in the state she calls home.

“It’s upsetting because it sends a message to the younger kids going through the education program thinking about grad school,” she said. “And it does not encourage them to go to grad school.”

If she had known as a graduate student that master’s pay was the next to be cut, Valenti said she wouldn’t have completed the program. Now, with the hindsight of everything she learned in graduate school, she said the experience is worth the money.

“I probably wouldn’t have chosen to go,” Valenti said. “But I think I really came into my own as a teacher during that time. My approach to teaching has grown.”

In post-graduate school life, Valenti has taken on more leadership roles at school. She better understands what education means and has a grasp on what it takes to impact different generations of students.

But when she looks at the landscape of education in North Carolina, she can’t help but associate the profession with stress and frustration.

“To feel that way in a profession that most of us go into definitely not for the money — it’s the passion that we’ve had since we were little — to feel that they’re not really listening to you with class sizes or money and salary — it feels like we are kind of pushed to the side.”

Uncertainty for teachers and graduate schools

With the reduced number of students enrolled for 2014, the future of Elon’s M. Ed. program is uncertain. Plans or changes to combat the tumultuous teaching climate are undisclosed at this time, but it’s a conversation that is taking place.

“The students who are currently enrolled in our program work hard,” Ansah said. “They study hard, and nothing phases them about getting their degree.”

But like many teachers grappling with changes to the North Carolina education system, Elon is taking it one day at a time.

Richard Mihans, chair of Elon’s Department of Education, said graduate programs are declining across the country, and children in the classrooms are the ones who suffer.

“If you don’t encourage people to continue their education with incentives, people will begin not advancing their knowledge base — but not because they don’t want to,” Mihans said. “If there’s no monetary incentive to do that, it just seems like it’s not fair.”

Mihans has seen the Elon M. Ed. students at work. He said it’s a rigorous and thriving program — for now.

With the extensive changes made to the North Carolina education system by the General Assembly, Mihans said he expected to lose some of those students in 2013.

“I thought we would see some attrition rates, but we did not,” he said. “I am concerned about the incoming class.”

On April 29 — two days before the application deadline — six deposits had been made, according to Mihans. Normally, he said, a new graduate cohort has approximately 30 to 40 students.

“That’s a little troubling, “Mihans said. “They’re waiting to see what the legislature is going to do.”

Elon’s program, which costs $10,000, is competitively-priced among other M. Ed. programs in the state. For out-of-state students, a master’s degree at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill can cost up to $14,229, and at North Carolina State University, it’s as much as $21,119.

The high prices of these other universities in conjunction with the elimination of the master’s pay increase have slowed down enrollment at other institutions as well. Enrollment at NC State decreased by 8.4 percent from 2012 to 2013.

Sarah Carrier, director of undergraduate studies at NC State, said the removal of the master’s pay raise has not only diminished enrollment numbers in master’s programs, but also chipped away at the morale of North Carolina’s teachers.

“The lack of attention to education in the state of North Carolina right now will be felt for decades,” Carrier said. “It’s amazing how quickly these poor decisions have had a negative impact.”

Despite aggressively recruiting teachers to enroll in the various master’s programs, Carrier said a lot of prospective students have opted out because they don’t think it’s worth it. And although they deserve compensation, she said, it’s hard to blame them for not spending the money.

“[With a master’s degree] partially, you have the compensation, which is really helpful,” she said. “The learning and growth as a teacher that comes from an advanced degree is even more so.”

In education for long haul

In Elon’s Department of Education, some students have held on to the hope that they will one day reap the benefits of an advanced degree.

Junior undergraduate student and elementary education major Grace Rubright said teachers aren’t attracted to the education field because of the money. Other aspects of the job are more gratifying.

“Every [education] major goes in knowing they’re not going to make any money,” Rubright said. “The reward is that you’ll feel satisfied with what you’re doing.”

Rubright said she plans to teach for several years before chasing an advanced degree. Inspired by her Elon professors, she ultimately wants to be a professor of education.

“I’m really passionate about working with kids and seeing when they start to learn something,” she said. “You get the best feeling in the world knowing you’ve helped them.”

Rubright hasn’t ruled out Elon’s M. Ed. program for when the time comes. Even so, the idea of teaching in North Carolina is a harrowing prospect. Rubright, who grew up in Pennsylvania — ninth in teacher salary nationally — said she plans to stay in the south after graduating from Elon but doesn’t foresee making North Carolina her permanent home.

“It seems like a very hard life to be a teacher here,” she said. “It seems like teachers are getting burned out really easily.”

But, for now, North Carolina schools can expect to continue pulling some of its teachers from Elon’s M. Ed. program. Suzanne Uliano, who enrolled in the Elon M. Ed. program in Summer 2013, plans to stick it out.

When she began the program, Uliano knew her decision to chase a higher degree was not the norm because her pay would likely not include the 10 percent pay increase.

“A lot of people have decided not to go to grad school. I wanted to go to grad school because I love learning,” she said. “I think to be an effective teacher, you have to be able to learn and grow.”

Although she sees room for improvement in the North Carolina education system, Uliano is optimistic she will see progress for teachers soon.

“Initially, pay is not good, and we’re not getting compensated for our master’s degree,” Uliano said. “But in the grand scheme of things, I’m very hopeful that things will change in the future. One day, people will be compensated for earning their higher degree.”