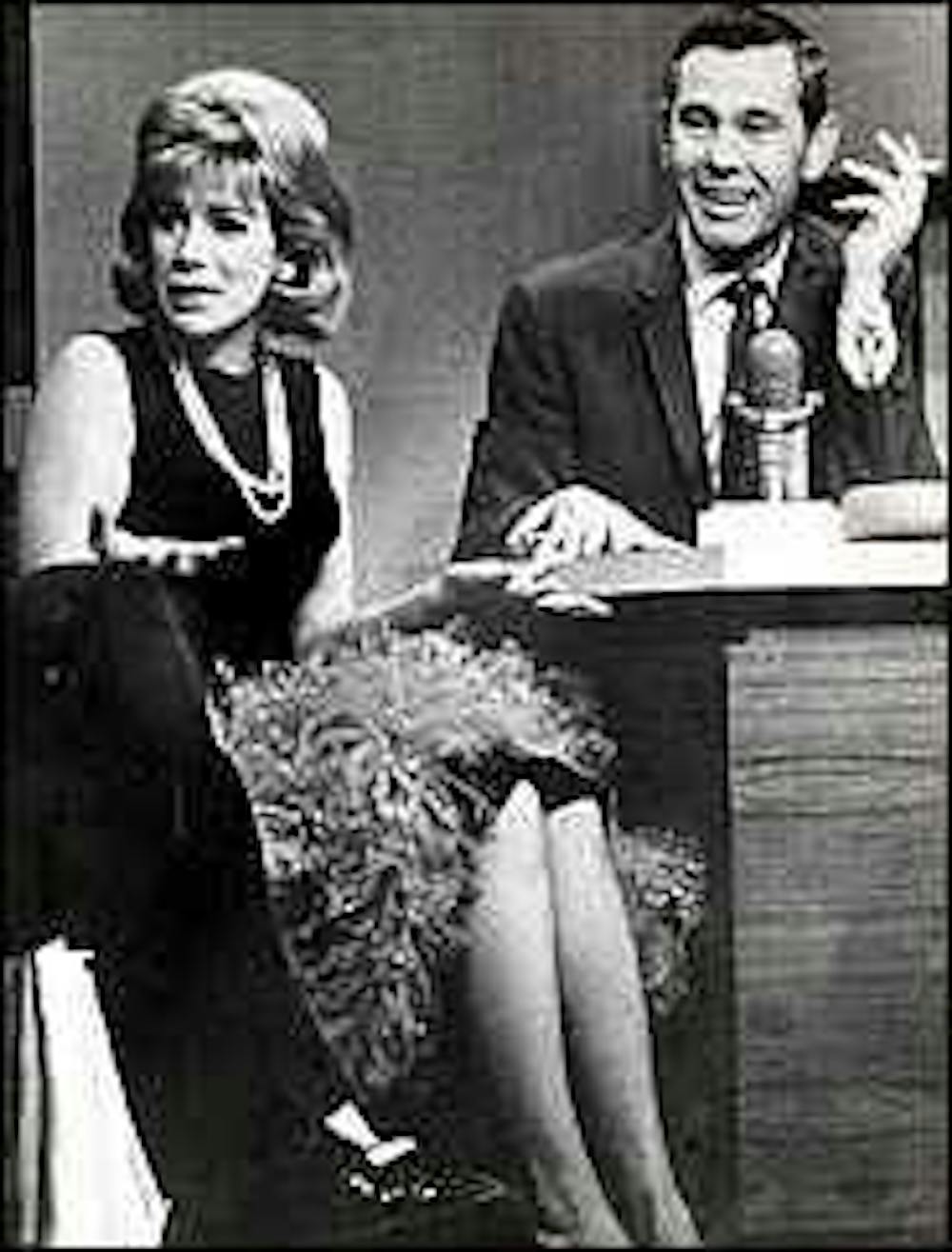

"Johnny Carson smoked, and for 30 years he was never pictured smoking a cigarette," Google C.E.O Eric Schmidt said in an interview with Maureen Dowd, featured in today's New York Times. "Today that would be nearly impossible."

This quote, aside from hinting at Carson's possession of huge quantities of invisible cigarettes, pertains to the ubiquity of personal information on the Internet, and Google's assertion that they don't have to give newspapers money in exchange for their reporting, that instead the news industry should alter its advertising model so that ads are personal and precise.

So what does this Carson quote seem to imply for the rest of us? Let's say we're not as famous as Carson is, and don't have a multitude of pictures taken of us that would lead to a startling (and untrue) assertion that he was never depicted doing something he always did. Let's say we have a Facebook account and there are several pictures of us at a baseball game. If the Google model is applied, somebody should be keeping tabs on those pictures and send an alert over to baseball-related firms to bludgeon

This sort of evolutionary, adaptive marketing has been all the rage across the Internet, and that's fine provided that it 's stuck to the articles we look at on Digg or CNN, or tailored to the interests we put into our Facebook status. Those are inputs that we voluntary toss to marketers, knowing full well that they'll result in directed ads.

The implications of Schmidt's quote about Carson lies with the distinction of personal information and public information. Despite what marketers will try to say (or those increasingly mischievous, mustache-twirling, profit-seeking 'do-gooders' Google folks, for that matter) there is a divide. Those pictures taken at a baseball field? Those are private, they're merely documentation of an event we attended, archived for posterity. If we're awesome, and have the Baltimore Orioles listed in our interests section of Facebook, that's something that's easily searchable, there's no intrusion.

But Schmidt's insinuation that things as personal as pictures, as small decisions made on a private scale, should be used by newspapers to try and hold up the corpses of their business models, is rather scary. Google's not supposed to evil, right? So why would they advocate marketers gaining access to our pictures and looking through all of them, trying to peel at what our preferences and predispositions as a consumer are? These are the same folks who would love to have our medical records. Should medical records be tossed to pharmaceutical companies so that they can tailor their ads to each individual customer? Will hemorrhoid sufferers eventually be bombarded with dancing Preparation H banners every time they log onto their emails?

I could be alone here, but I'd like to consider my life like a private residence. Sure, there are elements that are exposed to the outside world, you can drive by and take a peek at my car sitting in the driveway, see an Orioles banner maybe, maybe notice that there's a grill on the back porch. But I don't need the likes of Google, or the news outlets they're trying to push around, peeking through my windows and sifting through my garbage.