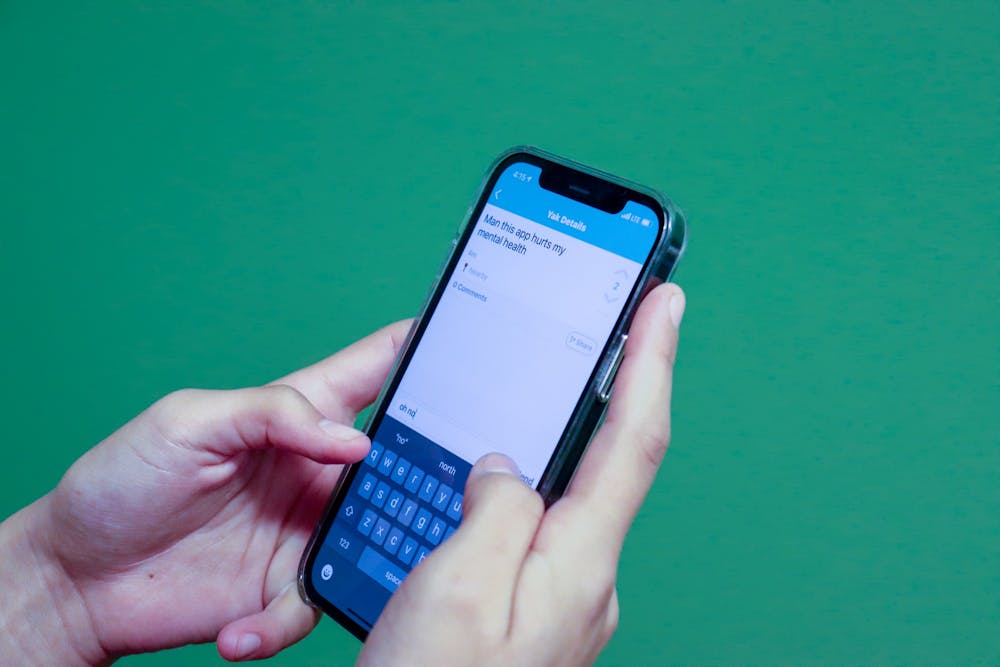

Everyday sophomore Maya Phinney scrolls through the social media app Yik Yak. Reading the anonymous posts, she pauses at a familiar name. As she reports the vulgar message targeting her friend, she can’t help but wonder who wrote it.

“People can turn any social media site or just any app in general into something negative,” Phinney said. “And that's an unfortunate thing.”

Yik Yak originally launched in 2013, quickly gaining popularity among teens. Prior to its removal from the app store, Yik Yak had over 200 million users. But the app became a hub for cyberbullying, and was shut down in 2017. The rights to Yik Yak were procured by new developers in 2021, and now, the Yak is back.

The social media site allows individuals to post and view anonymous messages to the feed of other users in close proximity to their current location. These posts, called “yaks,” can be upvoted, downvoted and commented on by other users. According to the current owners of the site, this anonymity is intended to provide “a place to be authentic, a place to be equal and a place to connect with people nearby.”

Many forget that freedom of speech on social networks can sometimes lead to consequences. Yik Yak has become an outlet for cyberbullying and deception, and students like Phinney are calling for reform in how it’s used.

Director of the North Carolina Open Government Coalition Brooks Fuller explained that the anonymity Yik Yak provides is nothing new. He said anonymous speech has been vital to political participation and letting people speak on the internet.

“People have used speech on the internet, under anonymous accounts, to share political dissent, important political speech all over the world. And at the same time, people have hidden behind the cloak of anonymity, to spread abuse and disdain for people and hateful rhetoric,” Fuller said.

As the app has made a comeback, so have its negative impacts. Fuller explained that the harassment present on Yik Yak has once again proven detrimental to the emotional and mental wellbeing of individuals. He noticed no change in the use of the platform.

While Yik Yak does have new guidelines in place meant to prevent cyberbullying, it hasn’t necessarily come to an end. Phinney said she frequents the app and has seen messages ranging from random information to targeting individuals. It can be anything from complaints about the McEwen ice cream machine to comments criticizing an individual’s weight.

“There's some random things, random funny things that people say,” Phinney said. “And then there are some not so nice comments, or people calling people out by name.”

On the occasion that Phinney knows a student identified in a Yak, she follows the guidelines, downvotes and reports the Yak. Otherwise, she said she does not interact with the app beyond scrolling through posts.

Phinney believes the app is merely being used by the wrong people for the wrong reasons, and that many don’t realize that the mask of anonymity only goes so far. Fuller said many users do not read the terms and conditions of the app. He warns students that there are limits to the protection provided by their screens. In this case, Yik Yak may be anonymous to other users, but it doesn’t mean the app has to safeguard an individual’s identity if they are subpoenaed by law enforcement to turn it over.

“When someone communicates a threat over any social media platform, as long as the social media platform is built so it has the ability to turn over that information, then they have to turn that information over to law enforcement — or they have to fight the subpoena,” Fuller said. “Most social media platforms are not willing to fight subpoenas on behalf of their users who threatened people.”

Though she sees more negative Yaks than positive ones, Phinney said she has never come across any messages that could be life-threatening to one’s safety. Ultimately, she maintains that the primary issue lies within the user, not the app.

“I think there's just a very fine line between using it appropriately and using it to be nasty,” Phinney said. “A lot of people don't really understand that, and they just kind of hide behind this anonymous profile and say whatever they want, but I think it should exist. I think just the wrong people have been using it.”

Freshman Mason Kaiser’s use of Yik Yak has declined since he noticed an increase in the hostility on the platform. He originally downloaded the app for entertainment and connection, but he has since then watched the app turn into a place harboring hostility, not community.

“Yik Yak is a great, fun platform for people to freely express themselves and ask questions that they might be too scared to ask directly to a source,” Kaiser said. “But with that comes a noticeable amount of hate between people.”

Fuller cautions users against believing everything they read on Yik Yak, as the confidentiality attracts cyberbullies aiming to deceive individuals or instigate arguments. Kaiser has identified false information about individuals he knows on campus.

“It creates these conditions that make it more likely that speech will appear on that platform that is either unreliable, or offensive or harmful in some way,” Fuller said. “ It’s like a lot of the internet, some of the mundane stuff is not really all that problematic. It's just kind of stupid or silly. But it can rise to the level of serious pretty quickly depending on what the content is. That anonymity tends to invite more inflammatory rhetoric.”

Fuller anticipates Yik Yak facing a similar fate as it did years ago. He does not believe its premise is sustainable, especially since the app hasn’t changed since its downfall. Unfortunately, many students don’t always take action when they encounter hateful or hurtful speech, and the way users engage with the app is revealing about the values of today’s society.

“The fundamental aspects of the design are not that different,” Fuller said. “It's just the terms and conditions and some of the internals that are a little bit different, but the way people use the app hasn't really changed. If it sticks around longer, it might tell us something about who we've become and who we are.”