Melissa Jobes’ children have had to go to the homes of friends in order to complete their school work remotely. Her family lives in rural Alamance County, an area that lacks internet availability in many places.

Remote and online work has been the reality for teachers and students in Alamance County for the past 11 months, and even as the county returns to in-person learning, three out of five school days will be remote.

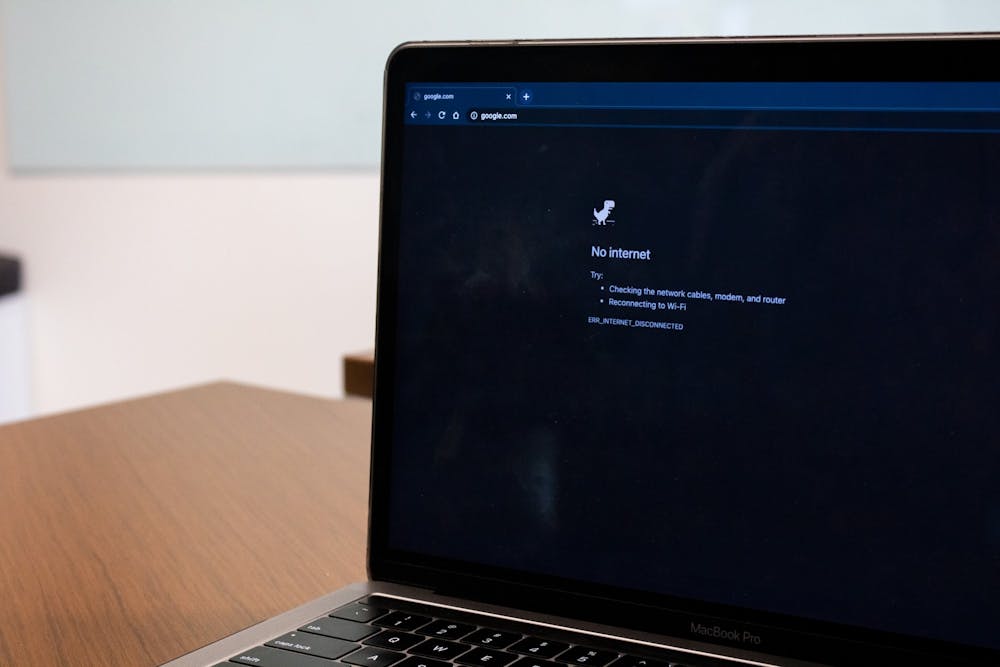

Teachers will still sit in classrooms with rows of half empty desks and be greeted by students on a computer screen, but for some kids, accessing the internet isn’t always feasible.

Alamance-Burlington School System has tried to bridge the digital divide — the gap between those who have internet access and those who don’t — as most schools have been engaging in remote learning.

ABSS has distributed 3,850 hotspots and 17,304 Chromebooks to students. This effort by the school system is to ensure that students who need access to the internet and technology can complete school remotely.

Jobes, the parent of a middle and a high school student, said her family received a hotspot from the school district. She said the hotspot has been helpful, but their internet connectivity issues still persist.

“We did get a hotspot from the school, but where we are, the connection is not great,” Jobes said. “My son is a senior this year and has been an honor student and is kind of struggling because he can’t get into his classes. A lot of the time, it’s really connection issues.”

As of 2019, 22.62% of households in Alamance County have no internet access. 14.92% of households have no computer and 31.38% of households have children, according to the North Carolina Broadband Infrastructure Office.

Connecting students to the internet

Along with the school system’s efforts to connect students to the internet, the county and state have taken steps as well. Alamance County Public Libraries has hotspots available at branches to check out for 28 days at a time as a part of their creating connections program. The public libraries received a $10,000 grant from the State Library of North Carolina to make hotspots available at branches in Alamance County.

The grant is a part of the Library Services and Technology Act grants that aim to promote digital equity. The SLNC awarded over $2 million in grant money in 2020.

Susana Goldman, director of the library system, said her department saw the need for the program before the pandemic, but they were inspired to make hotspots available for checkout once COVID-19 accelerated the need for expanded internet access.

“When COVID happened, all of a sudden the question of how much our community needed, it stopped being a question and started to be blatantly obvious,” Goldman said. “Because all the schools needing remote learning having to basically close schools down last [school year] and then having it continue for so long, the need just sort of grew.”

Goldman hopes to expand the hotspot program and have it funded through the library system’s budget after she saw the success of the program.

As the county and state search for solutions to the digital divide, connecting students to the internet goes beyond that. Mark Samberg, director of technology programs at North Carolina State University’s Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, works at the intersection of information technology and K-12 education.

Samberg said factors such as economics and location affect why people don’t have internet access. Hotspot programs at public libraries and schools are addressing the economic issue of internet connection, but don’t address location.

“Some of those barriers are economic in that internet access is expensive, families can’t afford it. And districts have done a really good job with that, giving out hotspots. That doesn’t do a whole lot of good for another whole group of families who can’t get internet access because of where they live,” Samberg said. “There is no cell service, the cable company won’t give them cable, they might be able to get satellite but satellite internet access is expensive and it’s not that good … so there [is] a significant number of people in North Carolina [for whom] internet access is just not an option.”

According to Samberg, hotspots won’t solve the lack of cell or internet service problems. If there is no internet service — whether it be by fiber, satellite or some other service — a hotspot or computer won’t solve the problem. 11.01% of households in the county have access to fiber. 0.63% have access to digital subscriber line — known as DSL — which provides internet access through phone lines.

“If you were there where there isn’t adequate cell coverage — and so that’s an issue — also … you can have the hotspots, and you can have the devices and you can give them out but there is going to be still a percentage of people who just can’t get it,” Samberg said. “Right doesn’t matter; like there’s just not anything you can do at their house where they live.”

Jobes, who has satellite internet that she said is “pretty terrible,” had a cellular company install a cellular reception booster. Satellite internet, coupled with the booster and a hotspot, still doesn’t provide the internet speed her family needs, according to Jobes.

“A lot of times we don’t, especially if it’s cloudy or rainy, we just don’t have the connection that we need. And only one of the kids can get on the hotspot at one time and it’s super slow,” Jobes said.

Economic and physical location barriers to internet access are often exacerbated by other factors, such as race and ethnicity, which further disadvantages students. Race and ethnicity widen the “homework gap,” which is the divide between students who have internet access and those who don’t. According to a 2018 Pew Research Center study, 25% of Black teens and 17% of Hispanic teens are unable to complete their homework because they don’t have access to a reliable computer or internet connections.

“There just are some barriers, which does tend to disproportionately hit students who are already underserved in the education system, right, so students of color, students from low socioeconomic backgrounds, students with disabilities who are already at a disadvantage,” Samberg said.

ABSS is sending some students who have internet connectivity issues physical worksheets and lessons. The public libraries also has a bus with WiFi that goes around the county to help students connect to the internet to do work. Samberg said solutions like these only address one area of connecting students to the internet.

Long-term efforts to connect rural areas to the internet

The state broadband office is working on long-term solutions to get internet access in rural areas. The Growing Rural Economies with Access to Technology program funds broadband service in rural areas. Grants from the GREAT program give money to private broadband service providers to establish internet access in North Carolina’s Tier 1 and Tier 2 rural census areas, as well as rural parts in Tier 3 areas.

Alamance County is a Tier 2 area, meaning it has a moderate level of economic distress, with Tier 1 being the most distressed and Tier 3 being the least. The county is ranked as the 68th most distressed area out of 100 counties by the North Carolina Department of Commerce. Counties 1-40 are all in Tier 1 — the most distressed. Property tax, population growth, median household income and the unemployment rate determine the tier and ranking.

Eighteen counties were awarded GREAT grants in 2020, but Alamance County was not among them. The county, along with 72 other applicants, applied for an application to receive broadband from Spectrum Southeast LLC. Ten broadband service providers were given $29.8 million, which is expected to connect 15,965 households and 703 businesses to high-speed internet.

The broadband office has given Alamance County’s broadband availability a score of 81.9% in 2019, a 6.1% decrease from the year before. The northern and southern regions of the county have the lowest broadband availability.

Jobes lives in southern Alamance County and said she’s moving out of that region, in part because of the lack of broadband service in the area.

“Just as the way things are going, a lot of things are remote now [and] it’s just not feasible to live in the middle of nowhere and not have any access to technology,” she said.

She said teachers have been understanding of their connectivity issues, but Jobes said her kids need a stable connection to get their work done.

“With the way society is now, everybody needs internet,” Jobes said. “I mean, it used to be a luxury, and now it’s a necessity for school [and] for work.”

Efforts to reopen school continues

While connecting students to the internet is an ongoing process in Alamance County and across the state, efforts to get children back into physical classrooms continue.

In March 2020, ABSS schools went remote at the onset of the pandemic. In the 2020-21 school year, only special education and pre-K classes have returned to in-person learning. For K-12 students, it’s been almost a year since they’ve been in the classroom. The school board’s current plan has K-5 students going back to class in-person March 1 and 6-12 March 8.

With ABSS' return to in-person learning, students will be assigned two days working in the classroom and three days working remotely. Group A will be in-person on Monday-Tuesday, Group B will be in-person Thursday Friday and both groups will be remote on Wednesdays.

The North Carolina House of Representatives and Senate passed a bill mandating that schools across the state return to in-person learning. Gov. Roy Cooper vetoed the bill on Feb. 26, and a veto override in the senate failed March 1.

Alamance County representatives Dennis Riddell (R- NC 64) and Ricky Hurtado (D- NC 63) voted for and against the bill, respectively. Sen. Amy Galey (R- NC 24), who represents western Alamance County and eastern Guilford County, voted in favor of the senate in-person learning bill.

Jobes said she’s hesitant to send her kids back to school in-person. She works as a nurse and said she is already potentially exposing her family to COVID-19 and wouldn’t want her family to be even more at risk for the virus.

“I’m a nurse and I have enough exposure without putting them [at risk] or even bigger exposure hazard. They’re kind of nervous about it as well,” Jobes said. “So again, another reason why we went ahead and decided to go ahead sell our house and maybe try to finish out the year with decent connection and have them be able to function a little better.”