“No blacks allowed. Whites only. No Spanish or Mexicans.”

Racist signage from the Jim Crow era or Tinder bios of today? Unfortunately, the answer is unclear.

There’s something deeply unsettling about seeing the blatant rejection of certain racial categories in print. Tinder bios stating “please no n***** chics and no Indians” or “if you’re black and we matched, it was probably a mistake” are concerning to most.

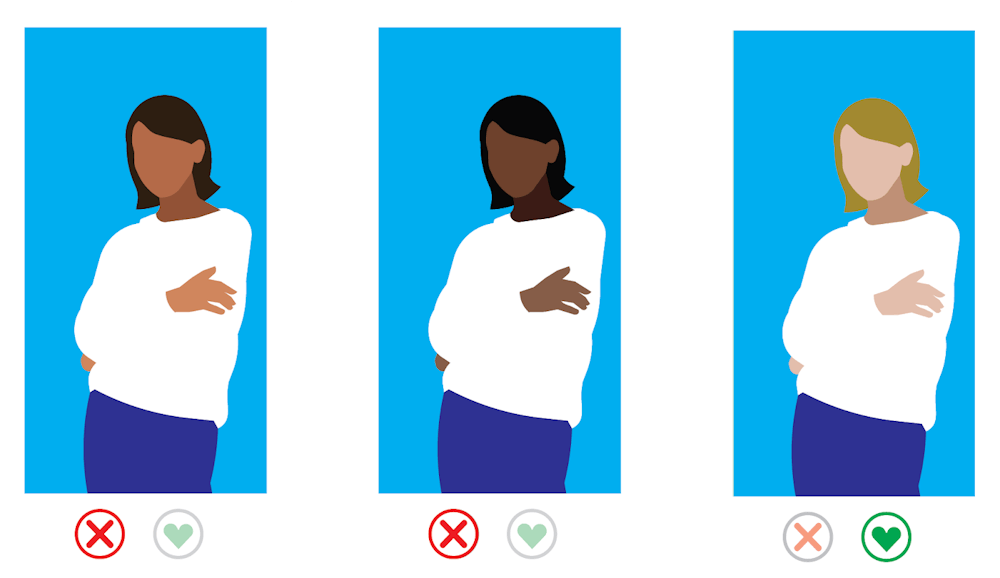

Yet many behave similarly without realizing it. Rather than outwardly rejecting certain potential partners of color, implicit bias operates subconsciously as we categorize certain people as potential dates or as candidates for rejection based on racial identity.

Individual preference is conceived as precisely that: individual. We perceive dating as something based upon intangible qualities: attraction, connection and ‘spark.’ Some would argue that racial preferences in dating are simply a matter of taste.

The misconception lies in the framing of the dating debate. Individual preference when replicated and magnified on a larger scale becomes a consistent pattern and ultimately prejudicial.

Preference, like most things, is a socialized phenomenon. It is a result, in part, of restrictive beauty standards, historical housing and school segregation and stereotypes associated with certain races.

Think Asian “geishas” or black “jezebels.” These factors collectively paint certain races as potential dating candidates, while others are perceived as either non-options or only casual “flings.” All too often, black women and Asian men are the losers in the dating scene.

There are certain shades to the dating debate. What about individuals who exclusively date members of historically marginalized identity groups and exclude white partners? White partners’ preference for a single minoritized race is often simply argued to be cultural appreciation, a compliment.

The issue with such appreciation is that single-minded preference for a particular race reduces individuals to stereotypical racial attributes, hence the problematic nature of fetishization and exotification of other races typified by “I only date…” statements.

None of this is to say that those with preferences are bad, intolerant people or that preference for those with similar experiences and backgrounds is innately wrong. Learning to love and appreciate other cultures as well as bonding over shared experiences and backgrounds are admirable.

Rather, this is a call to reflect upon implicit and socially taught bias; how has the society we live in shaped who we view as potential partners and the desirability of particular races? While legal segregation has ended in the U.S., social segregation persists and shapes who we meet and what roles we imagine they can play in our lives.

Unlike the blatant and rampant segregation of Jim Crow, dating preference cannot be resolved through legal sanctions or policy. Social change will require significant restructuring of power imbalances and mitigation of their negative effects in American society.

Individual change, however, is possible through personal reflection on one’s own dating history. It is my hope that individual awareness, coupled with increased integration and representation of diverse bodies and stories, presents a possible pathway to a world in which individuals are judged by the content of their character and heart, not by the color of their skin.