Over the past several months, presidential candidates have traveled across Iowa in search of support from the first voters in the 2016 election. Though the Iowa caucuses have garnered much media attention lately, it is important to recognize some limitations of the results.

Perhaps the most notable limitation is that the makeup of the Iowa population is not representative of the larger United States.

More than 90 percent of the state’s electorate is white, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In contrast, just 66.3 percent of eligible U.S. voters are white.

The limited minority representation in the Hawkeye State is particularly apparent with the lack of Hispanic, African-American and Asian voters.

A little more than 4 percent of eligible Iowa voters are Hispanic, 3.2 percent are African-American and 2.4 percent are Asian. These three groups comprise 34 percent of the national electorate.

While the last five Democratic Party winners in the Iowa caucuses eventually secured the party’s nomination, the last two Republican Party winners failed to receive the party’s nomination.

During the 2008 caucuses, Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) placed fourth at just 13 percent. Former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee won Iowa at 34 percent.

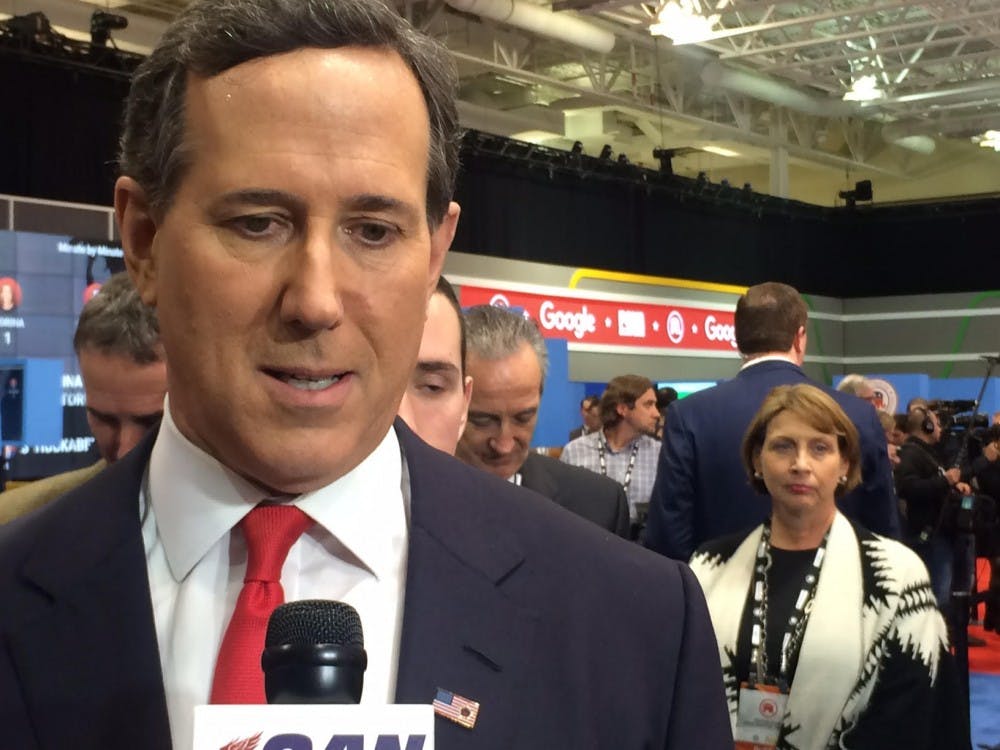

The 2012 caucus proved to be more competitive within the Republican Party, but former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum edged out former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney.

But the biggest weakness of the Iowa caucuses might be the voting system itself.

In the more efficient primaries, voters cast secret ballots for preferred candidates. States with open primaries allow voters to select candidates across party lines while closed primaries limit voters to candidates from within their affiliated party.

Caucuses require a greater time investment because residents cannot simply walk into a polling site to cast their ballots. Instead, they must arrive at one of the state’s 1,744 precincts and participate in the discussing of candidates, picking of convention delegates and dealing of state party business.

At Republican caucus sites, candidate supporters are allowed to campaign and make a brief speech before the paper balloting.

At Democratic caucus sites, participants divide into groups based on their preferred candidate. If a candidate secures less than 15 percent of the vote this year — as in the case of with former Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley — the group is disbanded and must join another group.

Between procedural complexities and an unrepresentative electorate, the Iowa caucuses receive far more attention than they deserve.

In order for Elon University students to gain a better understanding of the election, it is necessary to recognize the benefits of examining data from a more diverse region, such as North Carolina.

The Tar Heel State has an African-American population of 22 percent, an Asian population of 3 percent and a Hispanic population of 9 percent. Because the sum of three groups meets the national average, there should be more hype for the North Carolina primaries — a state that is of far more importance to the Elon community.