On the last Friday in September, Father Paul stands in front of a small crowd of Latinos and Hispanics at Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church in Burlington. They wait patiently to hear what he has to say.

Father Paul welcomes them in heavily accented Spanish, an unwavering smile spread across his face. He switches to English and invites an interpreter to help him with the rest of the information.

Members of the Burlington Police Department—including Chief Jeffery Smythe—sit to the right, listening to Father’s presentation about the FaithAction ID program and its purpose.

“This program is the result of a great deal of hard work, first and foremost, from the Burlington Police Department,” he says. “The Burlington Police Department, under the leadership of Chief Smythe, came to me and asked if there was a possibility that we could put this program together as a means of being able to better serve our community here in Alamance County.”

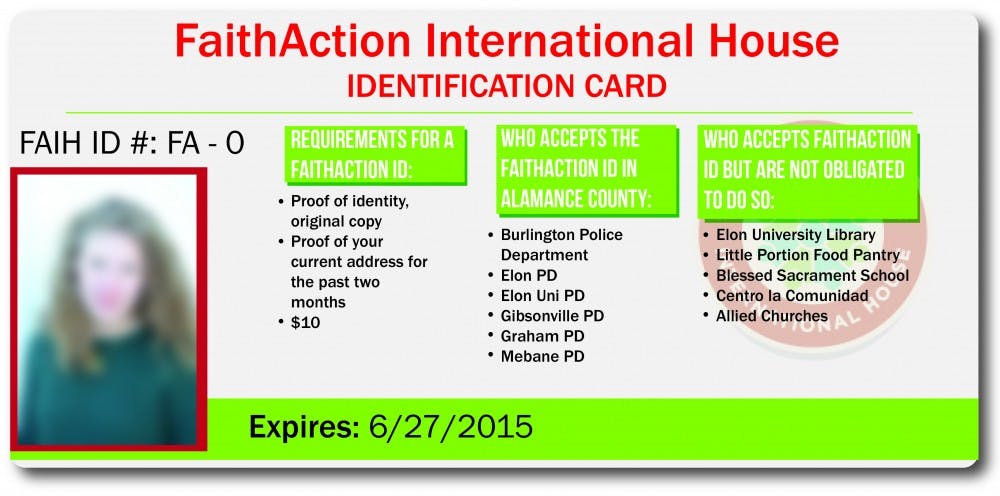

For the next thirty minutes, Father Paul explains how the process for obtaining the ID works, how it can and cannot be used, and who accepts it as a valid form of identification. He stressed multiple ways and emphasized many times that the police want to keep them safe, not deport them or hurt them.

FaithAction International House, a Greensboro-based non-profit that helps new immigrants adjust to their new life, created the FaithAction ID program in 2013 after a series of dialogues with the Greensboro Police Department on how to build trust within immigrant communities and minority groups in Greensboro.

Smythe saw the distrust and fear of the police as two of the central problems in Burlington upon starting his job as chief of police two and a half years ago. After meetings with FaithAction, other police departments in Alamance County and Father Paul all of last fall and into the spring, the Alamance County ID Task Force was formed. On May 26, 2015, the organization held its first ID drive at Blessed Sacrament.

“Our job is to make everyone feel safe,” he said. “We are here to extend a hand in friendship and trust, and build relationships so that when you have problems you can call us.

“Before, you might not have called the police because you weren’t able to show an identification card. But after today, you will have an identification card. And my hope is that that card will give you the confidence to call us when you need us.”

But the program that Smythe has worked so hard to bring to Alamance County—and Burlington in particular—could be considered illegal following a vote in the North Carolina General Assembly that could happen as early as Monday.

The bill under consideration, HB 318, tightens laws around E-Verify, an Internet-based system that employers should use to determine the eligibility of their employees to work either in the North Carolina or in the United States. Employers found a way around E-Verify, though, employing fewer than 25 people, the current number of employees a business can hire before needing to use E-Verify. The Protect North Carolina Workers Act would slash the number of hires down to five.

Another aspect of the bill nullifies any and all forms of identification that are not issued by a state or federal government.

That includes the matricula consular, an ID the Mexican consulate in Raleigh has issued for 20 years to its citizens.

It includes municipal IDs like the one Charlotte has considered creating.

It includes church- and non-profit ID cards. It includes FaithAction’s ID program.

“Things can be legal—that doesn’t make them moral,” said Vanessa Bravo, assistant professor of communications who has conducted research within Hispanic migrant communities. “If this bill passes, it will be immoral. The FaithAction ID doesn’t hurt anyone.”

Another bill that never made it to a vote would have made all of these types of IDs illegal as well, but it would have permitted undocumented immigrants in North Carolina to get a North Carolina driver’s license, valid up to a year. They would have to go through an intense background check and have insurance, but they would have had some form of identification.

Suyapa Mejia has worked for thirteen years for the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) at North Carolina State University, promoting healthy eating and habits for Hispanic and Latino families in Orange County.

Mejia says she has witnessed the effects not having a North Carolina driver’s license has had on undocumented men, women and children.

“These women cannot get prescriptions,” she said. “They don’t give them the medicine because they don’t have a license. This is what I have seen.”

Mejia says most of the consequences of not having identification hurt children, who may have been born in the United States or migrated with one or both parents. Without a license or other form of ID, Mejia says, fathers and mothers cannot take their children out of school if they are sick or need to go home early. When the state deports them for traffic violations, children are left behind and put in state custody.

Rep. George Cleveland introduced HB 318 as a way to protect jobs in North Carolina. According to him, undocumented workers in North Carolina take jobs from unemployed citizens of the state and the United States.

While the consular ID from the Mexican consulate has been in place for almost 20 years, Cleveland claims that the consulate has been issuing the matricula consular without needing much proof of identity.

Maria Monsalvo, public relations director for the Mexican consulate in Raleigh, says it is not true.

“To get a matricula consular, you need proof of nationality, like a birth certificate or a passport,” she said. “They need to be original documents. We do not accept copies. If we have a problem with the documents, we call and ask.”

In May, the consulate issued a statement reiterating to the General Assembly the importance of the matricula consular, its security features, and what it does and does not allow.

The ID is issued regardless of immigration status. It cannot be used to seek a social security card or a driver’s license. And even though the consulate does not allow criminals or those in a judicial process to receive the ID, Cleveland argues otherwise.

“They broke federal law by coming into this country illegally,” he said. “They are criminals.”

Smythe urged those present to get in touch with or have their friends contact Rep. Stephen Ross, one of Alamance County’s state representatives who approved the bill on the first vote who could not be reached for comment.

Smythe looked pained as he explained that the law has enough support to be approved, meaning he and his department could not help administer the program or accept the FaithAction ID as a form of identification. It also means the rest of the drives scheduled to be held this fall will need to be canceled.

“We’re changing lives with these people,” he said. “These folks are safer when they feel confident enough to call the police.”