As conflicts rage across Northern Africa, South Sudan, Syria and Iraq, refugees* are trying to find a way out. Countries like Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey have taken in millions of refugees and they no longer have the space or resources to take in anymore. Turkey has also experienced several bombings in the past few weeks that have scared people from seeking refuge there.

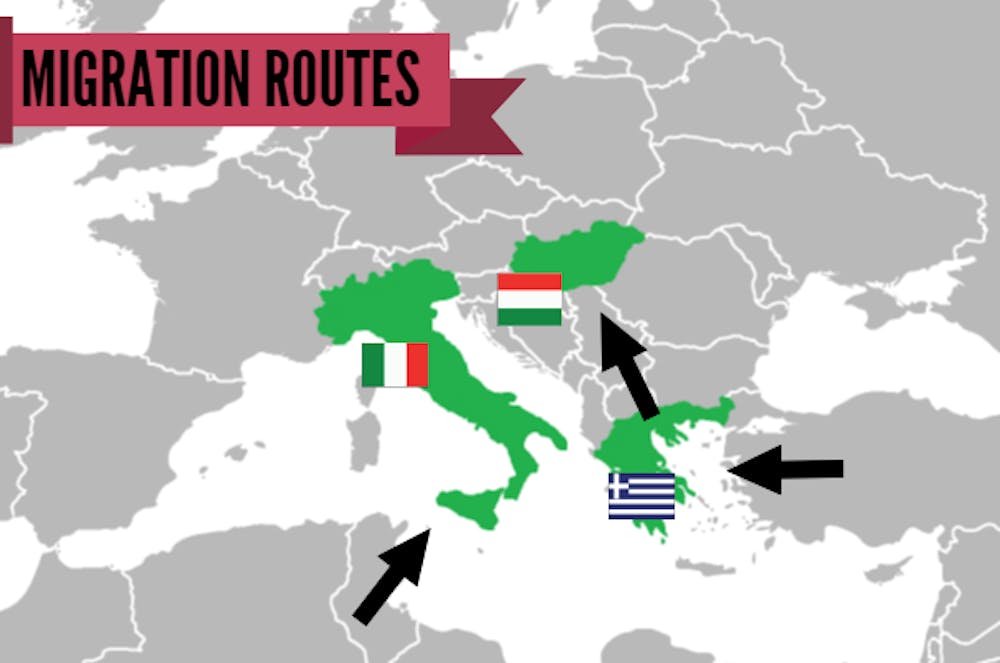

Instead, Syrians and other citizens fleeing their violence-ridden home countries are paying smugglers to take them across the Mediterranean to Europe. When they reach the shores of or set foot on the first European Union country they reach – usually Greece or Italy – the smugglers leave them. Sometimes, the smugglers dump them in the Mediterranean, leaving them to drown or to be rescued by the coast guard or immigration authorities.

Seeking asylum in the European Union

The International Organization for Migration has stated that nearly 365,000 refugees have crossed the Mediterranean in the last eight months. Ninety-nine percent of those refugees have landed in either Italy or Greece.

That law has put a burden on Italy and Greece. The two Mediterranean countries have argued that the law is entirely unbalanced; countries like United Kingdom do not have to process thousands of refugees daily. Under the Dublin Regulation, the doctrine from the 1970s that outlines the procedure for handling asylum and refugee seekers, the first EU country in which migrants and refugees arrive must process their claims and decide whether to grant asylum or deport them back to their home country. If migrants and refugees continue onwards to other member states and are detained, they will be sent back to the EU country from which they arrived.

Some countries, like Germany, have started to ignore this rule as refugees land undetected in Italy and Greece and continue their journey north to seek asylum. They allow them to apply for asylum. Others have done their best to keep them out. Hungary has built fences and walls to prevent migrants and refugees from entering.

Last week, the country also halted train service from Budapest into Austria to restrict further migration into the rest of Europe. As a result, thousands of refugees and migrants set out on foot to Vienna, Austria, a 300-mile journey on Sept. 4. As traffic built up throughout the day, though, Hungarian officials offered to bus the refugees marching and at the train station to the border.

The German government reported that more than 17,500 asylum seekers entered Germany over the weekend. The government has welcomed them, ignoring the stipulation in the Dublin Regulation which says countries can send refugees and asylum seekers back to the EU country they arrived in, but not all German citizens have embraced the welcoming policy of their government.

Finding a solution to the crisis

As the migrant and refugee crisis grows, so does the anti-immigration sentiment across Europe. Europeans – especially in Hungary and Austria – have recently elected right-leaning governments with hard stances on immigration. The tension this sentiment has created makes it difficult for the EU Council to decide how to deal with the influx of people.

Germany and France are calling for a quota system that would fairly distribute asylum seekers and take a huge burden off of Italy, Greece and – to an extent – Hungary. The president of the EU Council, Donald Tusk, has said that 100,000 refugees should be distributed across the 28 member states. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees released a statement on Sept. 4, saying the EU should accept 200,000 refugees.

But other member countries – Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia – would rather pay more in humanitarian aid assistance to the countries bordering Syria that have taken in more than four million refugees.

The United Kingdom believes taking in more asylum-seekers would further the crisis: more people would begin making their way to Europe. But, Prime Minister David Cameron announced on Sept. 4, that the UK would begin to accept thousands more Syrian refugees, who make up about fifteen percent of those applying for asylum in the EU, according to the UNHCR.

But he also stressed that those who will be granted asylum or refugee status are those who apply from refugee camps in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and other countries that currently host Syrian refugees. According to him, this route will prevent more people from making the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean.

*Note: The choice of the word "refugee" is a specific name for a group of people fleeing out of fear for their lives. Since the vast majority of those entering Greece and Italy are people from countries with histories of human rights abuses or that are currently war-torn, we chose this word to frame the crisis.