“It was like everything was just over.”

This is how Sam,* a veteran of the U.S. Navy, felt returning to civilian life after being employed by the Navy for four years. His sense of normalcy was gone, as was any hope of a daily regimen.

After four years of service, Sam said the transition from military to civilian life was difficult without having things in place upon return.

“You’re disciplined and geared in a different way, and when you come out it’s something totally different,” he said.

This is what led Sam to eventually become one of the more than 8,000 homeless veterans in North Carolina.

President Obama sets a goal

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, in 2009, President Barack Obama and VA Secretary Eric K. Shinseki announced the goal of ending veteran homelessness by the end of 2015. Through the Homeless Veterans Outreach Initiative, the VA is determined to meet this challenge.

John Turner, retired U.S. Army Capt., said it was brought to his attention in 2009 that veterans were returning home and finding themselves homeless. Turner, executive director of the Veterans Leadership Council of North Carolina — Cares (VLCNC-CARES), met with various people to form an organization designed to help veterans reintegrate back into society.

John Turner, retired U.S. Army Capt., said it was brought to his attention in 2009 that veterans were returning home and finding themselves homeless. Turner, executive director of the Veterans Leadership Council of North Carolina — Cares (VLCNC-CARES), met with various people to form an organization designed to help veterans reintegrate back into society.

VLCNC-CARES, located in Raleigh, aims to provide temporary housing, counseling, job training and medical and psychological care. Veterans are provided the necessary services to become productive individuals and reintegrate back into society.

“We’re looking at the most at-risk and needy population of veterans that exist,” VLCNC-CARES director of communications Jay Bryant said.

In May 2014, VLCNC-CARES received a $4.2 million community velvet block grant from the N.C. Department of Commerce. With that, VLCNC-CARES is currently renovating a building in Butner, North Carolina that will soon house 150 veterans.

The location of the building in Butner is in close proximity to the state mental hospital and an alcohol and drug abuse center. Bryant said they will be working very closely with those facilities.

“That is the veterans returning to self reliance,” Turner said. “Not just having a place to stay but going on and being productive and reintegrating back into the community — that’s our focus.”

Turner said he hopes the building will be ready by mid-summer 2015.

Brian Hahne, director of operations at Veterans Helping Veterans Heal (VHVH) in Winston-Salem, said their vision is to see homeless veterans shift from being consumers of resources to contributors of resources. Veterans with mental health issues can cost the system up to $70,000 a year with veterans going in and out of shelters, working with the VA.

VHVH is partnering with the VA for the Forsyth County Ten Year Plan to End Chronic Homelessness.

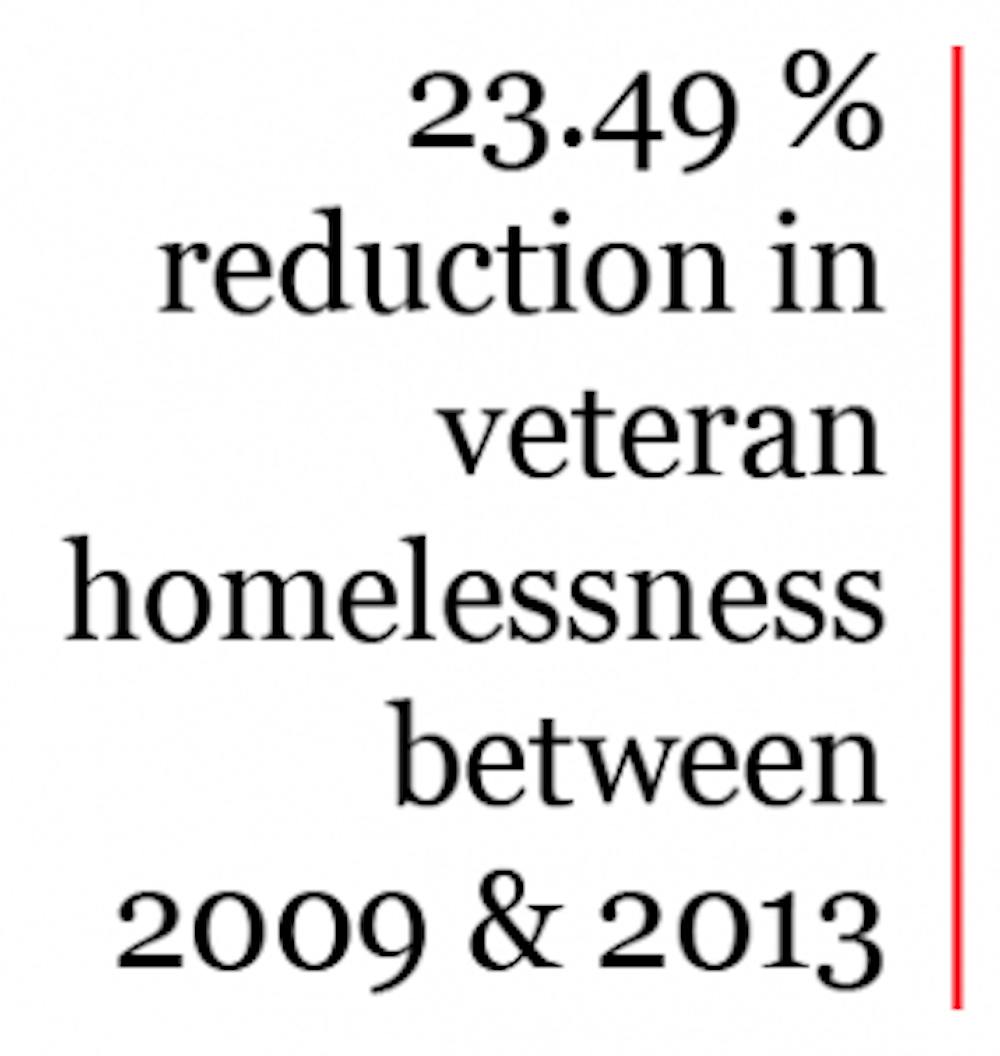

Nationally, veteran homelessness is decreasing. According to the VA, there was a 23.49 percent reduction in veteran homelessness between 2009 and 2013. The VA has increased programs and funding to push this progress further.

Path to homelessness

Shortage of employment opportunities can appear when people don’t have the skill set, grapple with substance abuse or mental health issues, or else don’t have a safety net.

These are some of the major indicators Phil Harris, director of Family Forum, said contribute to veterans potentially becoming homeless, the largest being family support.

Family Forum is located in Charlotte and provides transitional housing for homeless veterans. They offer services such as case management, meals, room and board, medical and dental care and substance abuse and mental health services. Family Forum is capable of housing up to 32 male veterans. Residents can stay up to two years.

“Unfortunately, the new guys coming home, some are in their early 20s,” Harris said. “You left high school basically just to serve your country.”

Michael*, a U.S. Navy veteran, enlisted at age 17 and did his three years of active service. When he returned home, he struggled with substance abuse and faced jail time for an old charge.

It was Christmas Eve when he was released from prison with just $150 in his canteen.

Harris said veterans come back and have no one to support them, so that’s when professional services come into play to bridge that gap.

“They’re not actually leaving to become homeless,” Harris said.

Sam and Michael are both residents of VHVH, a 24-bed transitional housing program. Residents are male, chronically homeless veterans in Forsyth County coping with substance abuse and/or mental health recovery.

VHVH has three main focuses: housing, services on sight (networking veterans into the community) and living in a community.

When Michael first arrived at VHVH, the clothes on his back were all he had. He said the camaraderie among the veterans is what makes VHVH so special.

“Most of them are going through the same thing I’m going through,” Michael said.

Sam had been through a variety of other programs but said he felt the shorter programs that range from 90 days to six months didn’t give him enough time to fully acclimate himself. At the end of the shorter programs, he said he went back to where he started from in what he called a “stagnant revolving door state.”

The first 90 days are a gray zone, Hahne said. The veterans have lost their families, and don’t know what their new beginning will be. VHVH focuses on fundamental life skills in those first 90 days. The next 90 days are to educate the veterans on executive functions including financial, personal and career planning.

“I’m just getting myself together, and then I have to go back to the street or back into survival mode, but here [at VHVH] they give you two years, and that gives you two years to acclimate and put yourself together,” Sam said.

VHVH has also helped Michael work towards a new career path. He is currently attending Forsyth Technical Community College and will graduate in May with an associate’s degree.

“You don’t want to go out and get yourself back being homeless,” Michael said.

Coming home

Some veterans don’t go home. They are unable to reintegrate back in society, which is where challenges arise.

Bryant said Turner has a phrase he uses when discussing housing homeless veterans. He often says, “A house is not a home.” It’s more than just providing a roof over their heads at night.

“You can be housed, but that doesn’t mean you’re home,” Turner said. “Home is more than just where you sleep. Home is feeling comfortable, feeling secure, being involved in the community. That’s when you’re home.”

“You can be housed, but that doesn’t mean you’re home,” Turner said. “Home is more than just where you sleep. Home is feeling comfortable, feeling secure, being involved in the community. That’s when you’re home.”

“And these people haven’t come home yet,” Bryant said.

Not everyone will make it through the program at VHVH, Michael said.

“You have to want it. If you want to succeed, I think you can,” he said. “I think it’s going to help a lot of veterans. I see a lot of change and growth.

The veterans at VHVH are given a structured lifestyle that includes weekly Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous meetings, chores and meals. The veterans at VHVH have a curfew at midnight. Between 6 p.m. and 12 a.m., all residents must take a breathalyzer test, and are drug tested once a week. There is a zero tolerance policy for drugs and alcohol to teach them accountability.

“I don’t know if you can ever end homelessness, but I think what you can do is you can work to develop programs like we are here [at VHVH],” Turner said. “You can increase collaborations across veterans network and strengthen the veteran network in the state.”

Turner explained that it’s important to keep these systems in place so if homelessness spikes back up, there are programs in place. An integrated statewide system for veterans care is important to prevent veterans from becoming homeless.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrjrC462p-0[/embed]

Video by Chris Price, reporter.

“It’s not something you can be like ‘well that’s done. Take all the resources that we’ve built and the infrastructure to solve this problem and scrap that,’” Turner said.

Both Turner and Harris said they have seen increased awareness about veteran homelessness.

“I would say I’ve seen more advertisements for homelessness and veterans overall in 2014,” Harris said.

Turner noted that the goal of ending veteran homelessness is a long road.

“It’s nothing you’re going to fix overnight,” he said.

Turning a corner

This past summer, Sam and Michael, along with other veterans from VHVH, volunteered with the summer food program for children at New Hope Church in Winston-Salem. Every day, Monday-Friday, they served 1,350 meals. On some days, they served anywhere between 1,500 and 1,800 meals.

At a VHVH weekly meeting, Hahne had residents describe what life was like when they were homeless and what life is like today at VHVH.

“It was a blessing to me not only that they got their food, but I got the opportunity to meet them,” Sam said. “It gave me a different perspective.”

The goal at VHVH is to create an exit plan; learning how to successfully reintegrate and become self-efficient. Michael and Sam have learned to take advantage of the opportunities presented and they both said you have to want it in order to succeed. VHVH has taught them to be accountable for their actions.

Every Tuesday night, residents of VHVH have a community meeting and Hahne has recently taken them over. In those meetings, Hahne gets to not only teach, but also learn about what it really means to be in their shoes.

“I come away each night on my way home knowing that I probably learned more than I taught,” Hahne said. “For me, it’s a privilege.”

* Names have been changed to protect the privacy of the veterans in treatment

Map by Chris Price, reporter.