A few weeks ago, the Internet was struck with Joseph Kony 2012 fever. #StopKony, #Kony2012, Uganda and

Invisible Children trended on Twitter for days, and posts were reblogged on Tumblr. The 30-minute Kony video created by Invisible Children, Inc. co-founder Jason Russell had one goal: to make Joseph Kony, Ugandan warlord and leader of the Lord's Resistance Army in north Uganda,“famous.”

The video also appealed to the International Criminal Court, asking the organization to capture and charge Kony with war crimes, including having an army of child soldiers and sexual assault crimes against women. But the fame Kony received during the campaign isn’t the right kind. The video itself is inaccurate and the facts presented have been manipulated.

The opening scenes show crying children in northern Uganda, whom the audience are made to believe are being terrorized by Kony. But Kony and his army, who haven’t been in Uganda since 2006, have migrated the surrounding countries in central Africa.

This fact, among many other pertinent ones, are strategically omitted from the video, and the atrocities committed against the people of northern Uganda are thus simplified for the Western audience. This isn’t the way to shine the light on devastation around the world.

“It gives impression that Uganda is still at war, people are still displaced, those many children are still out sleeping on the streets in Gulu and of course this not true,” said Amama Mbabazi, Ugandan prime minster, in a recent article published by The Telegraph.

Kony’s army has been operating since its creation in the 1980s, yet it’s only after a carefully edited video by a nonprofit that the rest of the world caught onto what’s been going on. Being informed about world events is wonderful, but people shouldn’t just rely on one-sided YouTube videos or Facebook groups to give them accurate accounts of world news.

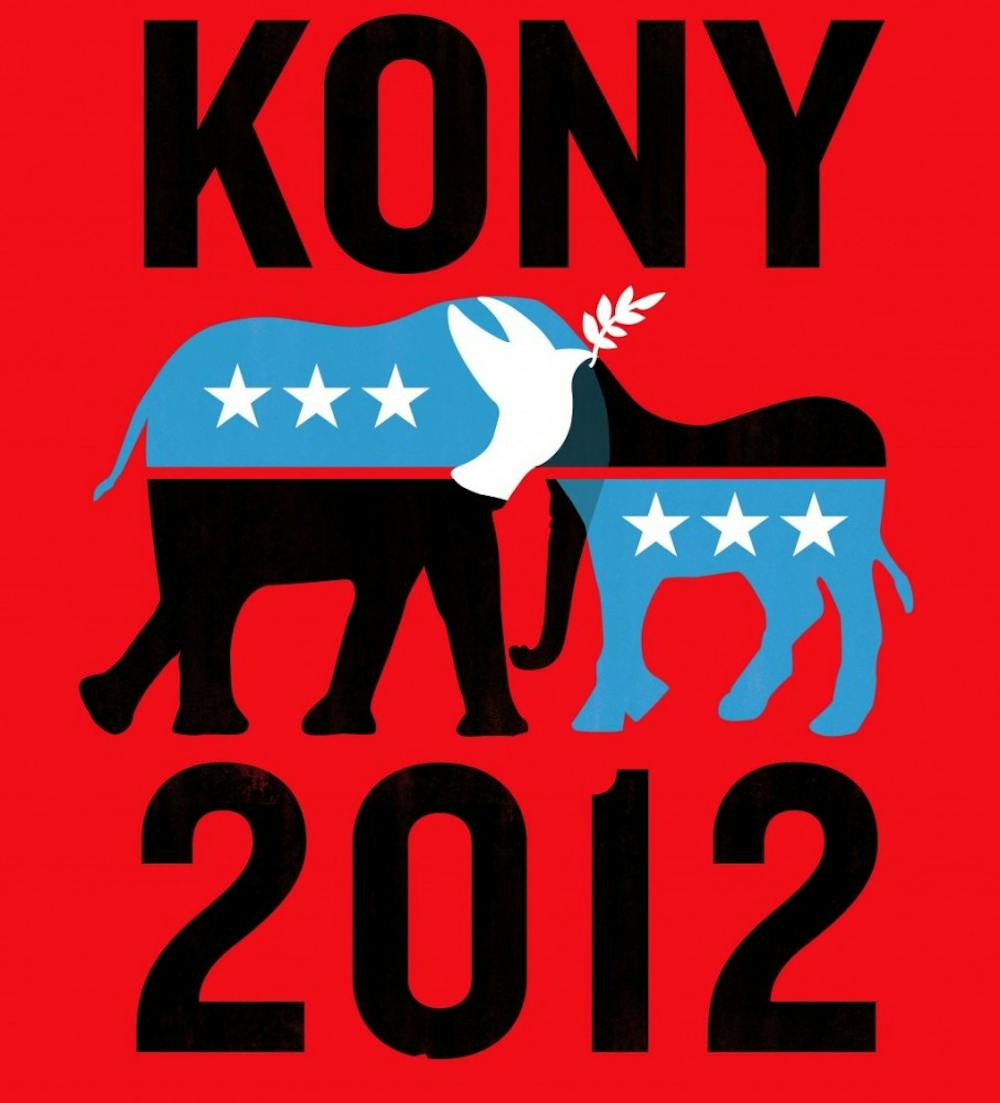

Invisible Children, the mastermind of this campaign, and its motives can and must be questioned when presented with the facts. The organization, founded in 2004, has created 11 films, including KONY 2012, about the LRA, and to go along with these films are wristbands, shirts and other merchandise. Because nothing says “I care” more than rubber bands and posters.

In a New York Times article from earlier this month, Russell admitted the organization sometimes inflates facts.

“No one wants a boring documentary on Africa,” he said. “Maybe we have to make it pop, and we have to make it cool. We view ourself as the Pixar of human rights stories.”

Teju Cole, a prominent anti-Kony activist, stated in a recent article, that “from the colonial project to ‘Out of Africa’ to ‘The Constant Gardener’ and KONY 2012, Africa has provided a space onto which white egos can conveniently be projected.”

In his article, "The White Savior Industrial Complex", Cole highlights the Western perception of Africa, a trend that Cole describes as an illusion.

“It is a liberated space in which the usual rules do not apply: A nobody from America or Europe can go to Africa and become a God-like savior or, at the very least, have his or her emotional needs satisfied,” he wrote. The disturbing thing about KONY 2012 fever is that it plays into the “White Savior Industrial Complex” or “white man’s burden.” Invisible Children is just another puppet that sends the message that Ugandans must be saved from their problems by white Westerners, because the natives can’t take care of themselves.