Members of the LGBTQIA community and people of color have always been discriminated against. But for people of color who also identify as LGBTQIA, they say they face double the discrimination — and the experience of having multiple oppressed identities is called intersectionality.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines intersectionality as “the complex, cumulative manner in which the effects of different forms of discrimination combine, overlap, or intersect.”

People — especially college students — often use identity to connect with others and exist in social groupings. But in cases where people may fit in multiple identity groups, identity can become complicated. It is even more complicated when those identity groups are marginalized.

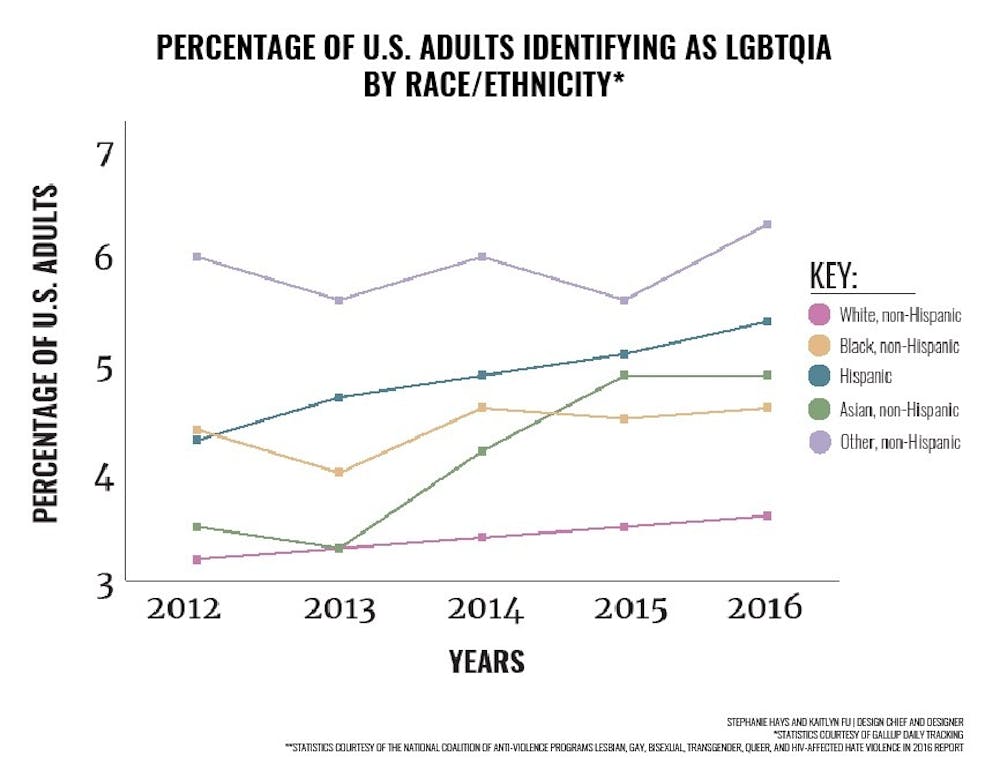

According to the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 40 percent of LGBTQIA adults are racial and ethnic minorities, but 60 percent of LGBTQIA and HIV positive people who report hate violence are people of color.

According to the American Public Health Association, black sexually marginalized men may be 1.2 times more likely to attempt suicide than their white counterparts.

With Intercultural Engagement being one of the four themes of Elon University’s 2018 Winter Term, students and faculty who identify in these groups want the conversation around this issue to open up.

Detric Robinson, community director for the Danieley Neighborhood at Elon University, said that from his own experience, queer people of color tend to focus on one aspect of their identity, essentially separating their identities and ruining what it means to be both.

“My partner and I identify as gay black men, but in college we explored our black identity and our gay identity at different points; I focused on my gay identity early on while my partner focused on his black identity,” Robinson said. “This comes back to us seeing those as two separate experiences during our times in early college, but now we recognize that we can’t separate the experiences of the two identities.”

Ann Cahill, professor of philosophy, argues that intersectionality creates problems around how others perceive those who exist in multiple minority groups.

“Our conceptual frameworks create the problems with assumptions built into them,” Cahill said. “It makes certain identities less than welcome, less than represented. They often feel like they have to correct the record.”

What it means to want

Many argue that attraction is objective; people like what people like and there is no rhyme or reason as to why. Cahill argues the opposite.

“It’s a conceptual confusion if those preferences exist separately from systems of autonomy,” Cahill said. “Your thing is not just your thing, it’s located in a social and political context; you have some responsibility for it.”

In her article, “Sexual Desire, Inequality, and the Possibility of Transformation,” Cahill argues that sexuality and preference cannot be reduced to a choice of this or that.

“Instead, as is the case with virtually and perhaps all elements of subjectivity, sexual desires, orientation, and identity emerge from a rich and dynamic intersection of materiality, social norms, historical location, and even choice,” Cahill said.

Junior Tres McMichael said his own experiences have shaped how he sees preference.

“When you start to talk to people about their preferences, they get really attacked,” McMichael said. “Your attraction is centered around race, something that isn’t changeable. You are not attracted to a major part of my identity; and that in and of itself is racism.”

According to McMichael, preference is largely developed as a result of comfort with the familiar. In his eyes, this is the reason why white, gay men find it difficult to talk to and date black, gay men.

“If you’re a white, gay male who lived in an all-white community, you don’t know what it’s like to have a black, gay male come into that community,” McMichael said. “It’s hard to change because if people are so focused on their attraction, they won’t be willing to reach out to those who are different.”

Sexology and the psychology of “The Other”

Online dating services provide more insight. Relatively private and remotely used, dating apps contain a slew of demographic information that reveals who people are and what people want.

Studies at various dating app companies reveal that white, gay males’ preferences are inherently skewed based on skin color.

At OkCupid, reply rates were measured between gay males of different races. Two important conclusions were generated. One, black, gay men receive fewer responses than any other demographic — about 20 percent less than non-blacks. And two, white, gay men respond the least to non-white men; they respond 15 percent less often and show a marked preference for other whites.

In the chances where white, gay men do message black, gay men, there are instances of fetishization.

“I am rarely approached by men without an assumption that I have a large p*nis or that I am a sexually aggressive ‘top,’” Elon alumnus Darius Moore ’17 said.

But neither fetishization nor sexual racism can be confined to black, gay men.

“When people find out I’m Latino, their demeanor changes towards me,” Matthew Antonio Bosch, director of the Gender and LGBTQIA Center said. “Some even use food terms to describe Latino, gay men, making references towards beans and rice, burritos, being a spicy lover — a papí.”

In being fetishized, queer people of color are inherently reduced to their skin color or the connotations that others have of people with darker skin.

This reduction can have many effects on a queer person of color’s psyche.

“Being a gay, black man means that I have to accept a lot of trauma,” Moore said. “A lot of trauma from family and friends. A lot of trauma from partners. A lot of trauma from institutions. ... It means that my white friend will always receive messages from men with zero expectations of him while I will receive a message once every three weeks from an older man who ‘loves dark features and aggressive men.’ It means that I will never have a place in the community.”

McMichael said he ultimately feels isolated.

“People won’t reach out to me or go on dates with me; I think that’s part of the thing that makes me feel not welcome at Elon,” McMichael said. “Gay men don’t know the implications that has with my feelings.”

Others, such as junior Julian Rigsby said the issue of being black and gay rarely crosses his mind.

“I don’t think about it that often,” he said. “I only think about it when a negative thing happens to me. It isn’t something I actively think about — only when something collides with who I am.”

Behind the virtual wall

A poll conducted by Travel Gay Asia and Gay Star News, two globally renowned gay online publications, concluded that 48 percent of gay men find companionship on gay dating apps.

But the culture of gay dating apps reveals a sexually racist climate that pushes queer people of color into a cycle of being blocked, ignored and outraged against.

The issue is more prevalent than what some might think.

According to a Gallup poll, 48 percent of LGBTQIA students of color experience verbal harassment because of both their sexual orientation and their race or ethnicity.

Regardless of the virtual medium to which queer people of color resort in finding companionship, many have felt disadvantaged as a result of their race.

“There are people on these apps that will literally put up ‘no blacks,’” McMichael said. “People have no shame saying that when going after a sexual experience, but in the real world, no one would say they wouldn’t have a conversation with a black person — but behind the fourth wall, it’s all fair game.”

For Chris Stolze, sophomore at George Mason University in northern Virginia, the effects of sexual racism can still be felt as a member of the Asian-American community.

“I am half German and half Filipino; however, all guys only see the Asian half,” Stolze said. “Since I am not a fit, white, gay male, I am immediately put behind thousands of gay men just because of my skin color.”

Redefining Pride

Many queer people of color point out that there is no easy way to change how others perceive them; the mindsets towards them from other identity groups are rooted in years of ignorance and misunderstanding.

Some think change exists in correcting standards of attraction.

“One thing would be opening up the idea that beauty comes from all bodies,” Bosch said. “If we cut ourselves off from that too early, then we really limit the possibilities for ourselves and instead perpetuate a narrow definition of beauty and of acceptance.”

Moore said that white, gay men need a reality check.

“Ultimately, white men need to challenge their inherent prejudices,” he said. “Learn the distinction between preference and fetish. Ask yourself why your expectations of black men are so much higher than white men. I am not asking anyone to force themselves to speak to a person of color just so that they do not perpetuate a cycle of oppression, but I am asking people to have the conversation.”