Freshman Rachel Kauwe has struggled with anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder since childhood.

Coming from a broken family, Kauwe has had anything but an easy upbringing. Her family never achieved financial stability, and Kauwe was nicknamed “poor girl” in high school. Desperate to find acceptance, Kauwe began to believe her classmates would be more accepting of her if she were skinnier.

In the midst of the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) annual awareness week — which runs Feb. 22-28 this year — Kauwe shared her story in the hope that it’d help the estimated 40 percent of U.S. college-aged females who have at some point had an eating disorder.

The week focuses on raising awareness of the severity of eating disorders and educating the public on causes, triggers and treatments. This increased awareness and access to resources can lead to early detection and intervention, which can help prevent the development of these disorders in millions of people.

“Eating disorders are a highly complicated, and often highly misunderstood, issue,” said Kelsey Thompson, a licensed marriage and family therapist associate in Burlington who specializes in eating disorders, anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. “Eating disorders are not a ‘diet that has just gone too far.’”

Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder — about 10 percent — but receive a fraction of the attention they need. In 2011, the average amount of research dollars per affected individual with an eating disorder was just $0.93. In contrast, the average for schizophrenia was $81 per affected individual.

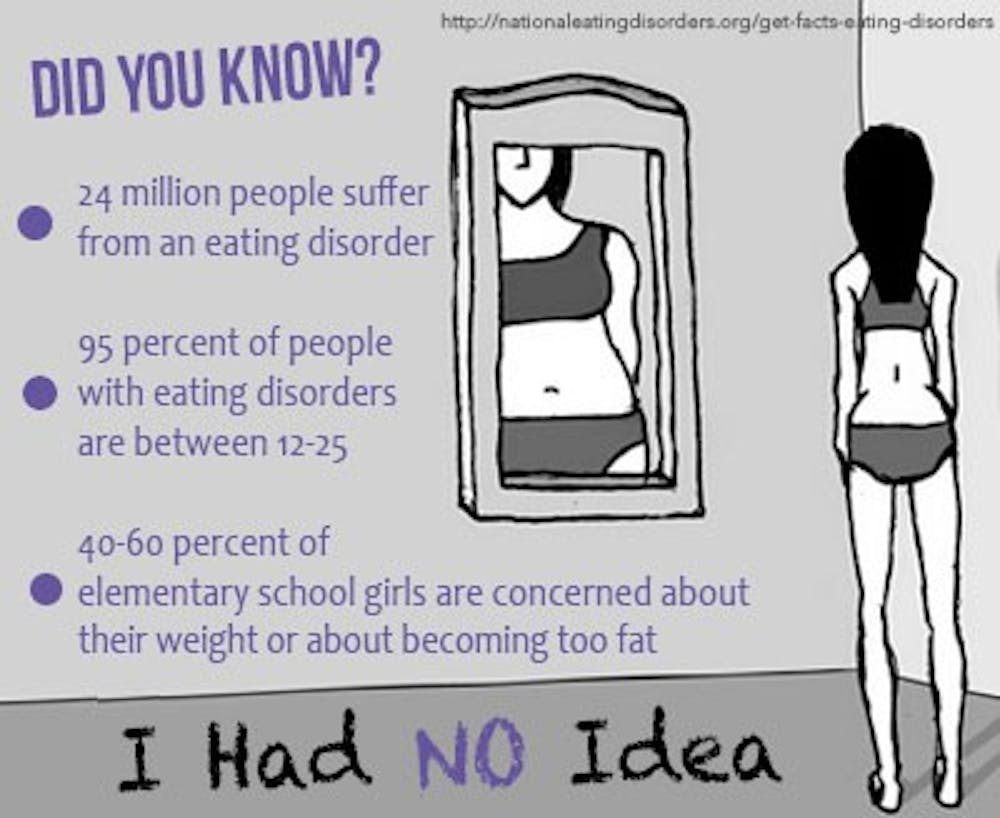

According to NEDA, up to 24 million people of all ages and genders have an eating disorder, with 95 percent of eating disorders affecting people ages 12-25.

But the numbers get higher among college students. The Multi-Service Eating Disorders Association reported that 40 percent of female college students have eating disorders, and 91 percent have attempted to control their weight through dieting. Anywhere from 10-20 percent of male college students are currently are dealing with an eating disorder, with anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder as the three most common.

Student-athletes are at a higher risk of developing eating disorders because of the emphasis on appearance, athletic performance, weight requirements and muscularity. Sports including gymnastics, diving, wrestling, running and swimming tend to focus on individual performance, rather than that of the entire team, which can allow an eating disorder to go unnoticed.

The type of training required of student-athletes can also contribute to chronic dieting, pressure to be thin and low self-esteem. Coaches who focus primarily on success and performance instead of the athlete as a whole contributes to the problem as well.

A week for awareness

The NEDA is taking a new approach to awareness week by focusing on the importance of early intervention. Intervening at early stages of development can increase the chance of stopping a full-blown eating disorder and its negative health consequences, so NED Awareness Week is directing individuals to a free online screening at MyBodyScreening.org.

This year’s NED Awareness Week’s theme is “I Had No Idea,” and is centered around the belief that thousands of people may have an eating disorder or may not realize the way they live, eat and take care of their bodies is detrimental to their health.

“We live in a ‘diet-ridden’ culture, in which all sorts of disordered eating behaviors are marketed as healthy, or the best way to have the body you want,” Thompson said.

Struggling with an eating disorder is different than any other illness because there is no medicine to take and the fight is against oneself. The symptoms are extreme, the treatment is hard and the process is long, but at the end of it, it’s about self-perception.

“Eating disorders, and the behaviors associated with them, often serve as an individual’s way of coping with emotions that feel unbearable,” Thompson said.

The fine line of recovery

Years have passed, but Kauwe admits that every day is still a struggle. In the malnourished mind of someone with an eating disorder, thoughts become distorted. The result is a continuous chain of unhealthy decisions.

“At times I feel like I have control, but then I also feel that food has control over me,” Kauwe said.

Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. These illnesses can be caused by genetic, psychological and emotional factors. Societal pressures to conform to a particular look or size can also take a toll. Many people attach their self-worth to the number they see on the scale, resulting in an obsession with numbers, calories and exercise.

“I’m really lucky how far I’ve come,” said a female freshman student who asked to remain anonymous.

Having struggled with an eating disorder since her freshman year in high school, she compared the dangerous mindset that comes with an eating disorder to a drug addiction.

“It takes over your entire life,” she said. “It’s not about losing the weight, it’s about the need for control and trying to get a grasp on your life.”

The student said she kept mostly secret because she feared what her family and friends would think of her if they knew. Although eating disorders are serious psychological issues, she was embarrassed and hesitant to confess she had a problem. Living in fear of disappointing her loved ones, she tried to deal with her struggles on her own, only to realize this was a battle she could not fight alone.

Although she was reluctant to reach out for help, the student now looks back and admits that telling her family was the best thing she ever did.

“The first step is the hardest,” she said.

These battles cannot be fought without the help, support and encouragement of friends and family. Although people with eating disorders may feel lonely, scared or lost, support from friends, family, medical professionals, therapists and former sufferers is available. “There are people that want to hear your story,” she said.

Recovery is not achieved overnight or even over the span of a month or two. It requires time, persistence, commitment and the desire to defeat an illness that prevents people from loving themselves.

Reaching out for support

Forced to sit back and watch his sister suffer from a life-threatening battle with an eating disorder, a male student who also asked to remain anonymous explained how painful and terrifying these illnesses are from the outside.

“My family is taking it pretty hard,” he said.

Once the student’s sister was admitted to a treatment center in Connecticut, family therapy sessions, daily doctor appointments and sleepless nights became the norm for his family.

In one of the group therapy sessions, the student’s sister admitted the first time she felt bad about her body image was in seventh grade. The entire family was shocked. They had no idea how long she had been suffering.

From an outsider’s perspective, an eating disorder may seem like nothing more than an innocent diet or desire to lose weight — but on the inside, it is a daily battle to survive.

“Eating disorders over time lead to increased anxiety, depression and feelings of isolation,” Thompson said. “The heart-breaking thing is, these are often the emotions that the eating disorder was developed to prevent in the first place.”

The health consequences of eating disorders include abnormally slow heart rate, low blood pressure, bone density reduction, muscle loss and severe dehydration that can result in kidney failure. Recovery is not simply the decision to regain one’s health — it is the decision to live.

Kauwe has taken these devastating effects and struggles and turned her recovery into something positive for herself and others.

“I don’t want to be known as the girl who has an eating disorder,” Kauwe said. “I want to be known as the girl who overcame her obstacles. [My eating disorder] has made me more empathetic, but more than that, it’s defined me.”

If you or a friend is struggling with an eating disorder they can reach out to Elon’s Counseling Service at the Ellington Wellness Center or (336) 278-7280.