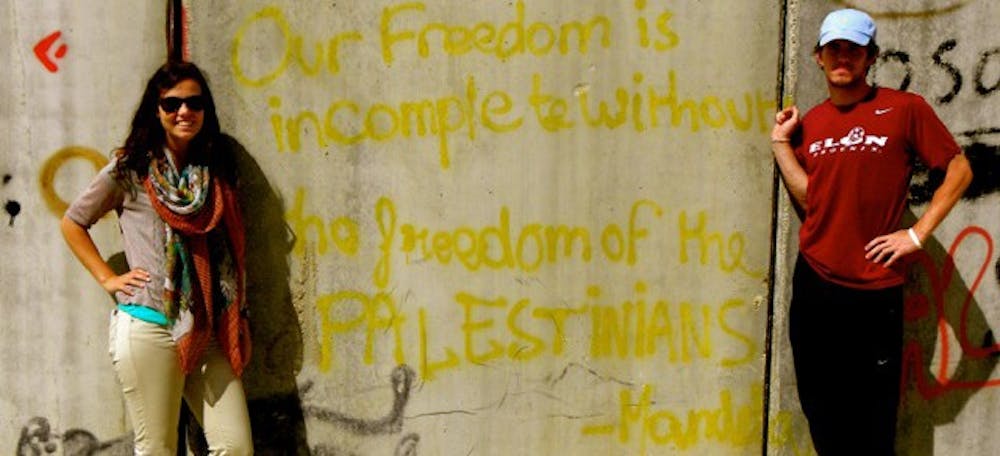

Elon University students Nicole Molinario, a senior, and Mark Berlin, class of 2014, spent the summer teaching English in the city of Hebron, in the West Bank. This is a recount of their time spent there amid the Israeli-Hamas conflict. Their opinions are their own and do not reflect that of The Pendulum.

As I stood fielding questions at the entrance of the refugee camp near my house with an M16 pointed directly at my chest, it was hard to imagine that just two months ago I had been sitting in my house in New York, excited to begin my time living and teaching in Hebron in the West Bank.

When I applied for the program, Mark and I assured our parents that we faced relatively few safety risks from the locals or from the soldiers who regularly patrolled the area. These assurances seemed laughable as I stared down the barrel of the gun, while a soldier interrogated me and examined my passport, amidst the debris from burned out tires, tear gas canisters and rocks.

My crime was simple — my taxi dropped me off outside a refugee camp that had put up a considerable amount of resistance to the soldiers' elevated presence. As an uncovered ajnabiyyeh (foreigner) I attracted a lot of attention. The soldiers wanted to know who I was and what I was doing in Hebron, particularly at such a tense time.

Eventually, they gave my passport back and sent me on my way. As I left, a soldier said to teach "them to stay the *expletive* inside in the afternoons."

The West Bank

As students of Middle Eastern studies, the options to live and intern for a summer in the region were limited by war and conflict plaguing many of the countries. We applied for teaching positions in the West Bank, its dialect of Arabic is similar to what we knew, and we felt our abilities could be best utilized there.

The West Bank, situated between Israel and Jordan, is currently under the limited authority of the Palestinian National Authority and its president, Mahmoud Abbas. It constitutes one of two areas of land under a degree of Palestinian leadership, and includes famous cities like Bethlehem, Jericho and Ramallah. The other, the Gaza Strip, is situated on the western side of Israel and bordered by Israel, Egypt and the Mediterranean. Gaza was granted relative autonomy by the Israelis in 2005 and has existed under a military blockade imposed by Israel after the election of Hamas in 2006.

We registered as teachers with the Excellence Center in Hebron, to improve our Arabic skills. We were sent to Dura, to work with the Moltaqa Sawaaed Center, an educational and volunteering center partnered with the Excellence Center, and teach four classes totaling 78 students ranging from beginner to conversational English speakers.

The ability to speak English is one of the greatest requirements for success for individuals throughout the region, because anyone pursuing a job or education overseas must demonstrate a high level of fluency. For Palestinians in the West Bank, knowing English is an additional necessity allowing them to share their experiences living under occupation with foreigners, who would otherwise never comprehend the realities they face.

Considered by many to be a microcosm of the larger occupation, Hebron was divided into two different sections — H1 and H2 - following the 1995 Oslo II Peace Accords. The Oslo Accords were an agreement between Israel and the PLO that created the Palestinian Authority and were supposed to eventually lead to a two-state solution, but talks ended up breaking down.

The legacy and pieces of the vision from Oslo, both those that were implemented and those that were not, remain a basis for future peace negotiations toward a two-state solution. In H1, the Palestinian Authority and police force are supposed to have autonomy over affairs. In H2, Israel retains “all powers and responsibilities for internal security and public order,” for both populations living within its borders, according to the Accords’ Hebron Protocol.

In areas where Israeli settlers and Palestinian communities intersect, tension is abounding, often leading to fighting between the two parties. Conflict within Israel and the Palestinian territories has been even higher since Fatah, the government of Gaza, considered by many to be a terrorist organization, signed a unity deal in April.

Arriving and surviving

We arrived in Hebron, a city of 180,000 residents June 14, two days after three teenage settlers were kidnapped while returning from school.

While here, we have seen this conflict greatly affects the lives of innocent children, regardless of nationality.

We saw this in our own students, through the news surrounding the kidnapping and in the response by Israeli officials with “Operation Brother’s Keeper,” which granted security forces “extensive operational powers to achieve the rightful and essential objective of finding the abducted teens,” according to B’Tselem, The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories.

Numerous human rights groups, including Israel’s B’Tselem, have characterized the ensuing crackdown as collective punishment of the Palestinian people, and our own experiences support that assessment. In the early days of “Operation Brother’s Keeper,” villages and roads closed. Restrictions expanded throughout the beginning of our stay, culminating in a travel ban on all males from Hebron between the ages of 16 and 50. Throughout this process, all borders and checkpoints remained open to us because of our foreign passports. This guaranteed we would be able to leave should the situation become too dangerous.

This travel ban prohibited my host father from attending his son’s graduation from Medical School in Romania. In the face of all the road closures, tanks and soldiers, it was the sight of my host father, tearfully Skyping his son’s graduation from his living room that drove in the most heartbreaking aspects of these policies.

Nightly raids, and numerous arrests by soldiers accompanied these closures.

Over the course of the crackdown, Israeli security forces arrested more than 550 Palestinians. The house Mark initially stayed in was raided just two nights after he moved into his permanent apartment.

We saw the effects of these raids most prominently in our classrooms. One day, while teaching the students English adjectives, we asked for example sentences.

We were stunned to hear “I am sad because the jayesh (army) arrested my brother” and “I am tired because the jayesh came to my house last night,” mixed in with the usual responses about joy at playing football and hunger because of Ramadan fasting. Despite the raids, arrests and road closures, our students came to class every day, excited to learn and participate in lessons.

Fellow volunteers Angelina Gaede, a German university student, and Amos Libby, a professor of Arabic and Indian music, experienced the worst of the conflict because their host families lived in exceptionally tense villages within Hebron. Gaede stayed with a host family within the city of Halhoul, where the bodies of the abducted teenagers were found and clashes occurred daily during “Brother’s Keeper”. Both were trapped in the streets during fights between locals and soldiers. Libby had to hide with members of his host family behind a building for several hours before the conflict receded enough for him to return home.

Soldiers shot another volunteer, Hannah Trate, a student at Ohio State University, in the chest with a rubber bullet when she was caught in the middle of an Israeli settler demonstration entitled a “Day of Rage.”

Mark and I experienced the conflict as well when, during a raid after 5 a.m. prayer, a 15-year-old boy, Mohammed Dudeen, was shot with live fire and killed by defense forces outside the center where we teach. Just like with the raids, the events of that morning colored the following lessons, and our adjective review was darkened by sorrow and fear because of the shaheed (martyr).

A violent end

“Operation Brother’s Keeper” officially ended on June 30th with the discovery of the murdered bodies of the Israeli teenagers, Naftali Fraenkel, 16; Gilad Shaer, 16; and Eyal Yifrah, 19, and with it came a decrease in raids, arrests and clashes from security personnel. However, this also marked the beginning of a period of retaliation against Palestinians, perpetrated by armed groups of settlers in the West Bank and angry Israelis in Jerusalem and cities around Israel.

Mohammed Abu Khdeir, also 16- year old, was brutally murdered as well, and with his death erupted a wave of Palestinian protests adding their own calls for revenge. One of our own students was arrested during this time for shooting fireworks — a common form of Palestinian celebration — and charged with “causing chaos.”

According to Al Jazeera, since we arrived in Israel, three Israeli teenagers and six Palestinians were killed in the West Bank. More than 120 Palestinians were wounded and 381 were detained.

In Gaza, more than 67 Israelis and 1,900 Palestinians were killed. More than 400 Israeli soldiers and 9,400 Palestinians have been injured.

When we greet our students in the mornings and ask how they are, knowing many have family in jail, or had the army in their villages the night before, the unequivocal response is always “I am fine, thank you. Have you seen the news of Gaza?”

The sheer generosity and compassion we have experienced here, from both our host families and complete strangers has been staggering, and the concept of solidarity between these people is inspirational. We have students in our classes ranging in ages from 6 to 55, many of whom have been arrested, mourned the death of a friend or a family member or have supported a policy advocated by Hamas.

Many of those who disagree with American or Israeli policy in the region are careful to make the distinction between the policies of a government and the sentiments of a people, and despite American support for Israel, we have been welcomed without exception with open arms.

These are the people the news labels as terrorists and inhuman, who are family members of the people currently living in Gaza. If we have learned anything here, it is that it is easy to paint this conflict with a wide brush, failing to attempt to understand the motivations and prejudices of both sides simply because of the complexity of the situation. But there is good and bad on both sides, and we are certain we will never forget the incredible generosity, hospitality, and hopefulness we experienced, in the hardest of times, in Hebron.