Farrell Moose is keeping an eye on his water. When the North Carolina General Assembly voted in July to legalize hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, in the state, he paid more than $300 for a baseline test of his well.

A statewide moratorium on fracking will remain in place for at least two years while the North Carolina Mining and Energy Commission (MEC) assesses the potential effects of shale gas extraction in areas over the Triassic Basins, but Moose wants to clearly establish his current water quality before the commission completes its study. He scheduled tests for inorganic compounds, which cost $33 each.

“If you don’t have a baseline test, you have no way of knowing if it was the gas companies that put the chemicals in your water,” Moose said.

Moose owns and operates Dutch Buffalo Farm in Pittsboro. He is one of many Chatham County farmers who fear the possibility of groundwater contamination or shortages as a result of fracking, a controversial method of natural gas extraction from subterranean shale formations. During the fracking process, the shale formation is drilled horizontally and injected with pressurized fluid to release the gas within the rock.

The debate over fracking has split the state of North Carolina. Some balk at the environmental risks of drilling near groundwater aquifers and using large amounts of water in the process, while others bank on the economic prospects of creating more jobs and strengthening North Carolina’s energy market.

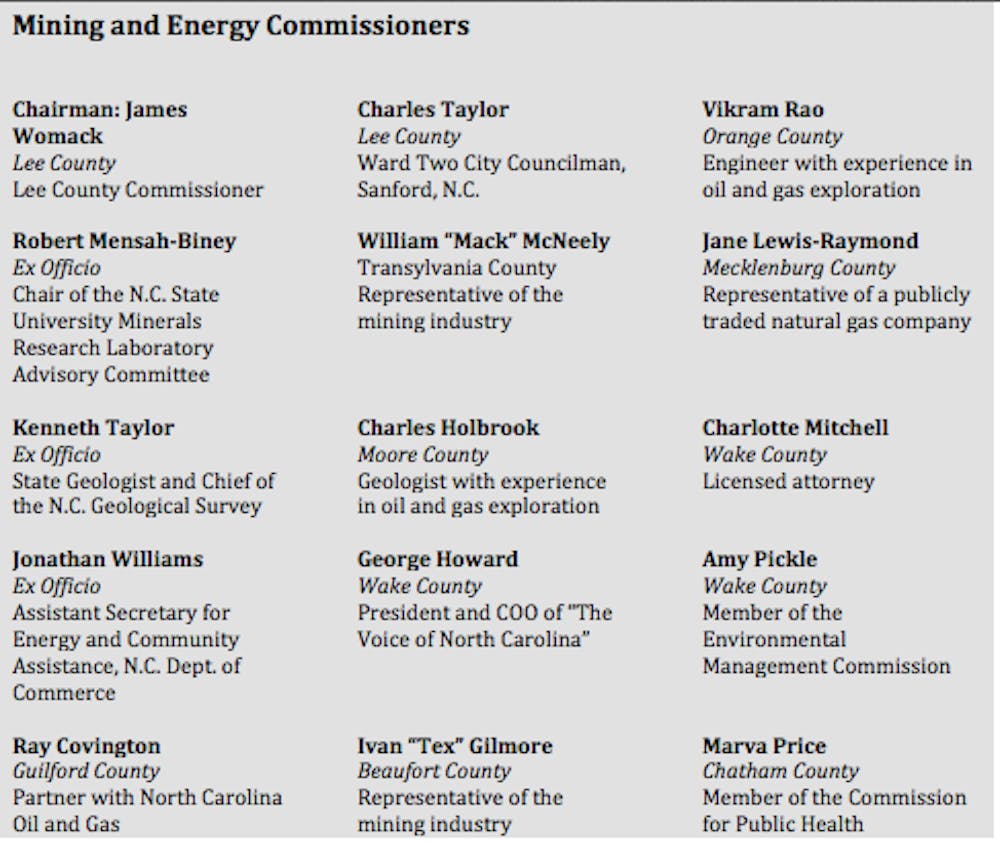

Senate Bill 820, the legislation that legalized fracking in the state, established the MEC to thoroughly examine both sides of the issue and update the state’s antiquated laws and regulations regarding vertical drilling for natural gas and related industrial developments.

“Here we have laws governing natural gas exploration that were written in the 1940s,” said Ray Covington, a Mining and Energy commissioner and owner of North Carolina Oil and Gas, a company that educates landowners about their mineral rights. “Let’s sit down and update the laws to make sure whatever we do is helpful to the citizens of North Carolina.”

In a report released in April, the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) asserted the need for stringent oversight of gas drilling operations to ensure the safety North Carolina’s groundwater and surface water reserves. The MEC was charged with the task of obtaining additional information about the fracking process in order to minimize the risk of water contamination, shortages and other fracking-related concerns.

The DENR report acknowledged several instances of groundwater contamination near hydraulically fractured wells in other states, though it noted some water quality problems were the result of industrial accidents that took place either before or after the fracking process was complete. The MEC will compare the policies and experiences of other states to determine the best set of natural gas regulations for North Carolina.

Fracking poses water risks

The DENR study found the distance between North Carolina’s groundwater and shale reserves is significantly less than that of other states, and the MEC is currently working to understand how the complexities of the shale layer might affect the risk of water contamination. Still, some environmentalists remain concerned.

“There is not a single state that has demonstrated that they can avoid problems, even with really deep shale formations,” said Hope Taylor, executive director of Clean Water for North Carolina. “There is certainly an increased risk due to the shale formations in North Carolina being so shallow, and a number of studies have drawn attention to the fact that its shallow and faulted, which is an additional conduit for contamination.”

Others opponents of fracking argue the state does not have enough water to sustain the natural gas industry without compromising the water supply of citizens and farmers surrounding the shale basin. North Carolina experienced two serious drought periods over the last two decades — one lasting from 1998-2002, the other from 2007-2008 — and some fear the 3-5 million gallons of water required to hydraulically fracture one well will further stress existing water resources.

Fracking promotes economy, green energy

On the other side of the coin, there are possible economic benefits to fracking, and the MEC is examining the degree to which natural gas extraction will boost the state's economy.

Using the IMPLAN model, the DENR report estimated drilling activity in the Durham-Sanford sub-basin will sustain an average of 387 jobs per year over a seven-year time period, and after all drilling activity is completed, the report estimated the state’s economic output would have increased by $453 million.

Fracking activity in other states is strengthening the natural gas market. The 2012 Annual Energy Outlook, published this summer by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, predicted natural gas exports would overtake imports in 2022. A recent revision said exports would overtake imports in as little as 4-5 years, as reported by Reuters.

Some regard natural gas as the first step on the path toward green energy.

“This could be energy for the next fifty years,” Covington said. “It’s renewable hydrocarbons. We need natural gas to make sure we have the bridge fuel for moving toward renewables. It’s so much cleaner than coal, and there is an abundant supply.”

Even if the MEC arms North Carolina with a comprehensive and proactive set of regulations to govern the safe extraction of natural gas through fracking, it is uncertain whether the industry will ever take root in the state. Many states have larger shale plays than the one in North Carolina, providing gas companies little incentive to burrow into a relatively small expanse of shale.

And if the moratorium was eventually lifted, it remains unclear how many wells would be drilled in Chatham County, where there is a lesser concentration of shale than in Lee and Moore counties.

Still, Covington said its necessary to fairly assess the possible risks and rewards of fracking in order to best prepare for the future.

“If you have the right rules and regulations, and if you fund it correctly, it can be done safely, but those are two mighty big ‘ifs,’” he said. “I will be the first to recommend no one does it if we can’t get it right.”

What's in the water?

In the eyes of some Chatham County farmers, fracking is a threat to their land, their water and their livelihoods. Many are closely watching the commission, for if the moratorium on fracking is eventually lifted, the regulations the commission suggests may affect the vitality of their farms.

Moose began following the progression of the nationwide fracking debate when hydraulically fractured wells began appearing in Pennsylvania, where several of his friends live and farm. Norma Burns, who owns and operates Bluebird Hill Farm in Bennett, also has friends in Pennsylvania who keep her updated on the gas industry’s activity in the state.

Burns said one of her friends, an environmentalist in Pennsylvania, told her there are instances of water contamination and other problems generally associated with natural gas extraction that sometimes occur without official explanation.

Stephen Cleghorn, a farmer in Jefferson County, Pa., said he knows of one such occurrence. He regularly transports water buffaloes from his farm in Reynoldsville to Woodlands, a small community outside Zelienople, Pa., that began experiencing problems with its water quality in late 2010.

After Rex Energy drilled at least 15 wells in the Zelienople area between July and December 2010, members of the Woodlands community fell ill after drinking and using their water, which was drawn from private wells, as reported by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Rex hired a third-party firm to test the wells for contaminants, and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection conducted tests, too. The third-party firm found no contaminants in the water, and the DEP could not trace the contaminants it found to the drilling activity in the Zelienople area. Because no baseline tests had been conducted on the wells prior to the drilling activity, members of the Woodlands community could not challenge the claim.

“Even the DEP had no proof the water had been fouled by drilling activity, but water was fine until the drilling came in,” Cleghorn said. “They had to discontinue using it for drinking, cooking and showering, and all they use it for now is their toilets.”

But Covington said the development of shale gas drilling in other states provides North Carolina with a particular advantage.

“Pennsylvania was the first state to start drilling for oil back in the 1800s, and their oil and gas laws have evolved over time,” he said. “I know there are laws Pennsylvania would like to have that are very difficult to implement at this point in time because of how their laws have evolved. I’m hoping that in North Carolina, we can assess the best laws in the country and bring recommendations to the legislature that will be the best laws in the country.”

Moose said even a slight risk of contamination is a major cause for concern.

“There’s nothing you can do once the groundwater is contaminated,” he said. “I live off my well and farm off my well, and the risks outweigh any potential benefits.”

He said he plans to schedule another baseline water test soon.

Past droughts fuel farmers' concerns

Some farmers worry about the possibility of water shortages, too.

“There is a lot of concern about having enough water for all of our needs,” said Doug Jones, owner and operator of Piedmont Biofarm in Pittsboro. “In a dry year, people with wells in some places are getting dry, and the water supply is becoming inadequate for irrigation. As our climate changes and our weather gets hotter, we’re going to need more and more irrigation of water to grow good crops, and if there is the destruction of water supplies, that can’t happen.”

Though Sam Groce, the agricultural extension director of Chatham County, said he is neither for nor against the idea of fracking in the state, the possibility of water shortages concerns him, as well.

“We do know that we can be water limited here,” he said. “We only have a certain amount to work with.”

But not all Chatham County farmers are alarmed at the possibility of fracking in the area. According to Groce, some recognize it as an economic opportunity.

Burns said she understands why some farmers have adopted this viewpoint, though she adamantly disagrees with it.

“There are some farmers who are are desperate,” she said. “Small family farms especially. It’s not an easy life.”

Moose said he thinks only a few people will share in the economic benefits of fracking, while many others will be forced to bear its potentially negative effects.

“My main concern is the loss of agricultural service,” he said. “They project they’re going to be in and out in nine years, but the damage could last forever. The people who think the government is all hard numbers are wrong. It is very difficult to put a monetary figure on the loss of agricultural use of the land for an indefinite period of time. It's the government's responsibility to foster business, but more importantly, to protect our common resources for economies and generations to come.”

Organic certification questions remain unanswered

Of the Chatham County farmers concerned about water contamination, some with organically certified farms are doubly worried. Obtaining organic certification is an expensive process, and the loss of certification could mean the loss of income for certified farmers.

“I sell 20 percent more by being organic,” said Judy Lessler, who owns Harland’s Creek Farm in western Pittsboro. “If my water was contaminated, it definitely would affect my organic certification.”

Burns, a certified organic farmer, harbors similar concerns.

“I have to be so careful about anything that gets put on my plants,” she said. “Should we have fracking and should there be a national concern or a statewide concern, I’m sure that would be added to the organic certification process.”

Though a loss of certification would affect Burns’ profits, she said it would mostly affect her on a personal level.

“Organic certification is part of my farm identity,” she said. “It costs me $500 to get certified each year. If I lost it, I’m sure I’d see a decline in sales, but in terms of absolute losses, I have no data. I am certified because it’s something that I believe in, and that’s my reason primarily.”

But problems with water quality could mean a loss of more than just her certification, she said.

“If the water quality was disrupted to cause issues with certification, the produce would likely have been compromised,” she said. “Then certification would be a moot point.”

In Pennsylvania, where fracking is a well-established industry, some certification agencies have amended their certification guidelines to account for the possible risk of water or soil contamination sometimes associated with natural gas extraction. Pennsylvania Certified Organic requires its farmers to stay abreast of extraction activity in their areas and revise their organic system plans accordingly. But risks associated with any industrial development are often unpredictable, and PCO “reserves the right to issue non-compliances associated with gas drilling after approving the Organic System Plan,” according to its guidance document on natural gas exploration and drilling.

Although many organic farmers in Pennsylvania are worried about losing their certifications, Kyla Smith, certification director at Pennsylvania Certified Organic, said none of the farms certified by PCO have lost their certifications since fracking activity began in the state.

“Many farmers do not like fracking on principle, and I think they may wish that there was a more definitive line that would preclude an organic farmer from organic certification,” she said. “However, it is not so black and white. It really does depend on the particular circumstances farm to farm.”

Bryan Snyder, executive director of the Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture, expressed a similar viewpoint.

“Everyone seems to be asking this same question regarding the effects of fracking on organic farming,” he said. ”As far as I know, there are no official answers out there."

Study committee considers forced pooling laws

One study group will partner with DENR and the Consumer Protection Division of the North Carolina Department of Justice to compare the state’s current forced pooling policies with those of other states currently fracking for natural gas and modify the policies if needed. North Carolina’s forced pooling law, which was originally written to regulate vertical drilling for natural gas, currently affords DENR the right to require landowners to integrate their properties into a single tract.

the state’s current forced pooling policies with those of other states currently fracking for natural gas and modify the policies if needed. North Carolina’s forced pooling law, which was originally written to regulate vertical drilling for natural gas, currently affords DENR the right to require landowners to integrate their properties into a single tract.

If a significant percentage of landowners within a proposed drilling unit agree to lease their gas rights to an oil and gas company, forced pooling laws require holdout landowners to integrate their property into the unit. Fracking enables drillers to extract gas from a wide area surrounding the well, and drilling units negate the complex legal question of what gas came from where. All landowners within established drilling units share in royalties paid by the oil and gas company.

Proponents of forced pooling insist such laws benefit both the land and the landowner by minimizing the number of wells within a unit and ensuring all landowners are properly compensated for the gas extracted from underneath their properties, but many opponents think forced pooling laws encroach on landowners’ property rights.

The recommendations of the study group, which must be reported to the Joint Legislative Commission on Energy Policy and the Environmental Review Commission by Oct. 1, 2013, could determine if a landowner has the right to refuse to integrate into a proposed drilling unit.

“That group will absolutely look at every state in the nation that is actively mining for natural gas or oil,” Covington said. “We’ll look at those states and their policies and assess the pros and cons and try to come up with how those policies differ from our current forced pooling law. If you look at our current forced pooling law, it’s very broad.”

Though Moose is opposed to forced pooling, he said the recommendations of the study group will have little effect on his overall peace of mind in regard to the possibility of fracking in his area.

“If my three neighbors sold their rights and rigs were getting set up on either side of me, I’d already be in hot water, wouldn’t I?” he asked.

Study committee examines power of local governments

A second study group authorized under Senate Bill 820 will determine the extent to which local governments will be able to regulate oil and gas activities through zoning or other local ordinances. This group will collaborate with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the North Carolina League of Municipalities, and the North Carolina Association of County Commissioners to gather information and present recommendations to the Joint Legislative Commission on Energy Policy and the Environmental Review Commission by Oct. 1, 2013.

“These limits on zoning and local regulatory power would be one of the factors controlling whether local governments could establish special agricultural districts that might regulate certain types of oil and gas activities expressly or pass generally applicable laws that also would restrict oil and gas development in some way,” said John Humphrey, principal of the Humphrey Law Firm in Washington, D.C., and former director of policy development at DENR.

Covington noted the establishment of such districts would likely give rise to a new set of questions.

“The organic farmer thinks differently than the corn, soybean or tobacco farmer,” he said. “Incredibly different mindsets. It’s easy to say you’re going to carve out all these agricultural districts, but the reality is every district has its own unique set of issues.”

He acknowledged the interest of maintaining a viable farming community in Chatham County.

“How is that all affected?” he asked. “That is something we need to think about.”

From the perspective of a Chatham County produce farmer, Moose said he thinks allowing local governments to establish special agricultural districts is a good idea.

“Special agricultural districts might let people decide whether they want their land to be agricultural or industrial or post-industrial,” he said. “They would at least put the question on the table and give farmers a voice in the debate.”