Nine years ago, Phil Bowers was the vice president of sales for a chemical company. The position was a good one, he said, and he lived a comfortable life. Then, he visited East Burlington, the “other side of the town,” the side that he didn’t know much about, and all of that changed.

Nine years ago, Phil Bowers was the vice president of sales for a chemical company. The position was a good one, he said, and he lived a comfortable life. Then, he visited East Burlington, the “other side of the town,” the side that he didn’t know much about, and all of that changed.

Bowers said he was “shocked and unaware at how prevalent” violence was on the streets of East Burlington, compared to the west side of town. However, Chris Verdeck, an assistant chief with the Burlington Police Department, told The Burlington Times News in January of 2013 that there’s little difference in the crime rates between East and West Burlington, with Webb Avenue acting as the dividing line between the two sides (see graphic). In fact, according to Verdeck, in 2012, the cases of aggravated assault were extremely similar on both sides of town. In the same year, there were more robberies investigated in West Burlington than on the east side. Verdeck didn’t discuss shootings, murders or any other violent crimes that Bowers alluded to when speaking about crimes “on the streets” of East Burlington.

In August of 2013, the Burlington Police Department launched an online map detailing crime in Burlington accessible to anyone with Internet connection. Recent crime statistics from this map tell a different story, juxtaposing the two sides of town as seen in the graphic below.

The statistics above are further laid out in the September 2016 map and its corresponding key below. This provides a visual representation of where the crimes took place. Webb Avenue, the boundary between east and west, is noted by the red line.

Despite hearing about crimes on the other side of town, Bower said he initially didn’t acknowledge the violence.

One day, however, the disparities between the two sides became too much. “What I’ve learned is the opposite of love is indifference, and that we’re asking people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps with no boots,” Bowers said.

According to Bowers, how the court system went about prosecuting these crimes was even more surprising than the violence itself. He didn’t understand why the courts forced felons to pay their way out of the system, when those in jail don’t have any money to begin with. This encourages a perpetual cycle of imprisonment, he said.

“It just seemed crazy to me that if we have a system that requires economic payment or restitution but there was no system in place to help them find legitimate work,” Bowers said.

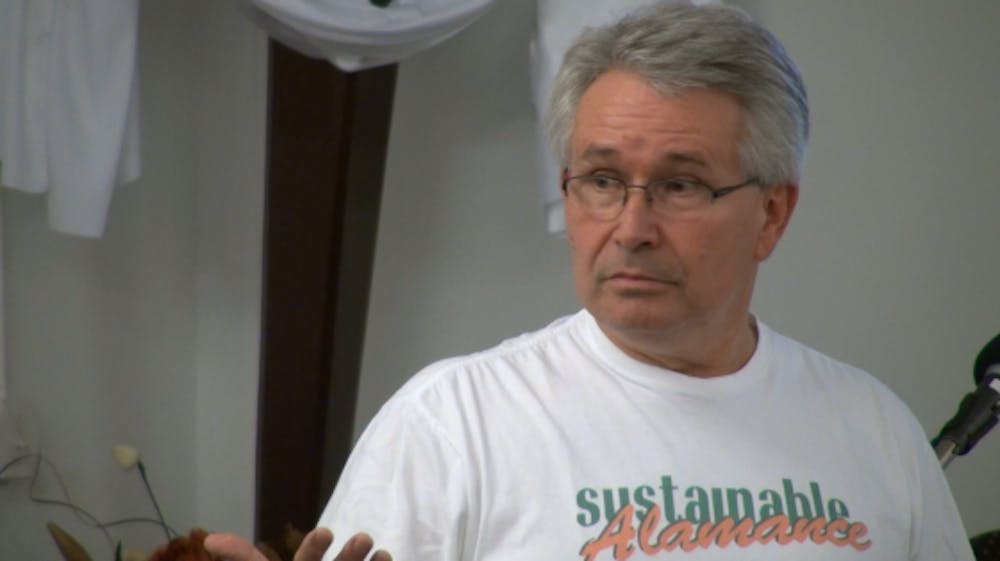

This concept was so “crazy” to Bowers that he quit his comfortable job at the chemical company and launched Sustainable Alamance nine years ago. The organization branded itself as a “poverty alleviation nonprofit.”

“Maybe it was just the right time to make the transition. So, I left all of that other stuff behind and came down here to help a different group of people, I guess you might say,” Bowers said.

“Maybe it was just the right time to make the transition. So, I left all of that other stuff behind and came down here to help a different group of people, I guess you might say,” Bowers said.

His initial goal was to place this “different group of people,” namely former inmates, into paying jobs so they could not only pay their way out of the prison system, but provide for themselves and their families, as well, Bowers said. Foreign to this side of town, the court system and the people he was trying to help, Bowers said he found out the hard way that simply giving someone a job doesn’t fix a person.

The first person Sustainable Alamance placed in a job didn’t show up to his first day of work, Bowers said. The next few disappeared after the first couple of paychecks, and a handful ended up back in jail. Bowers decided he needed to reevaluate the focus of his organization.

“I think too often we give people jobs who are coming out of poverty or whatever, and miraculously they’re going to know how to be middle class,” he said. “It just doesn’t work that way.”

Bowers decided then that the organization needed a new focus, a focus Bowers called a “mentoring program.” This new approach targeted relationships between the attendees and their relationship with Bowers, not simply specifying what the law says they’ve done wrong.

In the almost decade that Sustainable Alamance has been around, it has placed 70 former felons into full-time work. According to an economic impact study by professor Steven Bednar’s class in January of 2016, Sustainable Alamance contributed at least $3 million in benefits to Alamance County in the past five years.

“There’s a lot of hurt, a lot of trauma, a lot of craziness in life that lands people in the prison system, and you can’t fix that with a paycheck,” he said.

Although the program has contributed millions of dollars to the local economy, Bowers said it is difficult to get any sort of assistance with the program because he is working with a group that send many people running in the opposite direction.

“This is a population that has been given up on. It’s very hard to recruit volunteers, it’s very hard to get donations into a population that most people are really trying to stay away from.”

Rather than let it discourage him, Bowers said he attributes this challenge simply to “the messiness” of the work he is involved in. “It [the program] does work, but it’s really, really messy work. It is so much easier to raise money to just pay power bills than it is just to do this. You can do that and go home at night and your phone won’t ring. It’s a whole lot easier,” he said.

Although type of work is “easier,” Bowers said it’s not as rewarding work. Bowers acknowledged that, yes, those in his program are labeled as criminals by society. These “criminals,” however, have never been taught what proper behavior is.

“This is new for a lot of these guys. They’ve never had someone care about them. They’ve never had a grown man hug them,” he said.

In the reevaluation of the program’s vision, people who walk into Sustainable Alamance don’t simply get dropped into jobs. Instead, they begin with smaller day jobs under the organization’s supervision. Bowers said this allows the program to monitor their work habits, relationships and conflict resolution skills.

He also urges attendees to come to the weekly Wednesday meetings so he can get to know him or her. “If you can’t come sit with me for me to get to know you and figure out what you’re about for an hour a week, there’s no reason for me to believe you’re going to go to work 40 hours a week,” Bowers said.

Requiring people to come to meetings and holding them accountable not only helps those walking in the doors of Sustainable Alamance, but also helps Bowers get to know him or her, he said. “Once you know someone’s name, everything changes. It’s not just an ex-convict, as they [the public] would say. It’s Mike, and it’s Tommy. It’s Tony. That changes everything,” Bowers said.

He takes pride in maintaining certain requirements from the people who attend Sustainable Alamance. These requirements, such as coming to weekly meetings, showing up to work and keeping Bowers updated, separates Sustainable Alamance from the typical “charity,” he said.

“Our model of helping people is what we would just say as development work. I do believe that if you’re only involved in doing relief work where you just pay the bills or give food or whatnot, you can also create dependency,” Bowers said. “What we want to continue to do is find ways of helping people earn the money to pay the bills … I think there’s a lot more dignity in that.”

Through this approach to his program, he notes that his eyes have been opened to some of the underlying problems in the community. “You start uncovering things that you know they need to work on. I think it [the new vision] has been foundational to their success,” Bowers said.

Success that Bowers has helped harness. He said, however, the men and women who walk into his meetings have already succeeded by making it out of the streets.

One of those people that got the resources he needed from Sustainable Alamance is 27-year-old Gregory Elliott from East Burlington. Elliott is a self-proclaimed “drifter,” coming to Sustainable Alamance off and on for the past five years.

He didn’t feel comfortable disclosing what landed him in jail, simply saying, “I wasn’t in a position to say I was a law-abiding citizen. I was still doing whatever I wanted to do.”

He didn’t feel comfortable disclosing what landed him in jail, simply saying, “I wasn’t in a position to say I was a law-abiding citizen. I was still doing whatever I wanted to do.”

Elliott’s cousin brought him to his first meeting. He said what appealed to him most about the program was exactly what Bowers prides himself on: not simply being a “charity,” and instead providing life resources.

“They have more to offer than what you are used to, and once you realize that they don’t want anything in return, it’s just be a good person. That’s amazing, because everyone wants something, but Sustainable Alamance just wants you to do right by yourself and pay it forward to the next person,” Elliott said.

He said Sustainable Alamance helped him realize that he didn’t have to face the world by himself after getting out of jail. “It’s a great feeling to not feel alone, and when you’ve been in the system and you’ve been incarcerated you feel alone, because once you get back on the outside, people look at you differently and you are shunned,” Elliott said.Sustainable Alamance not only changed how he thought about facing the real world and its stigma against him, but also changed his “self-absorbed” mindset.

“People come in here and think, it’s me, me, me, and then you realize it’s more than me, me, me. It’s a brotherhood and a sisterhood. However you want to say it, it’s a family and to grow as a family, we have to be able to be honest with one another, and there’s a lot of honesty here,” Elliott said.

At the head of this family, is Bowers, whom Elliott credits for his success and other’s. According to Elliott, if it wasn’t for Bowers, many people who attend Sustainable Alamance wouldn’t “be in a positive place in their life.”

Elliot said he knows this “great place” is working, that it’s an effective program, not only because of the differences it has made in his life, but in the lives of those he grew up with.

“We have people here that are bringing people in and a lot of people I know. A lot of people here I know and I grew up with and I know what they did, and that’s how I know it’s real,” he said. “That’s how I know Sustainable Alamance is real, because along with myself some of the people that I’ve seen in here, that are involved in the group today, we were the worst of the worst and some of us didn’t get caught for the things we did but we know what we’ve done.”

Looking forward, Elliott said everyone in this Sustainable Alamance family’s individual past will still haunt them. They will always face a stigma because of the things they did and didn’t get caught for. What’s the key to combatting this stigma? Elliott said he tries to not let it bother him.

“You still have those people who are fighting against you, and it’s hard, it’s really hard, but when got somebody you can call and talk to or when you have other people who are in your position who you can call and talk to, it makes it easier. It makes it easier,” Elliott said.

As far as Bower’s forecast for the future? He said his “dream” for Sustainable Alamance is to figure out a way to connect with the younger generation, the ones out on the streets right now.