Be it through a two-minute video released by a passerby or a less-than-30-second clip from a police vehicle’s dash cam, recordings have played a vital role in fueling conversation — and, in some cases, division — on issues surrounding the shootings of black men at the hands of police.

A team of Elon University students, led by seniors Emmanuel Obi and Keith Davis, strive to change the narrative with a solution: “Our Watch,” a system for the distribution of these recordings.

Our Watch serves as a social media platform that helps citizens, law enforcement and the judicial system collaborate to protect their communities. Law enforcement officers with dashboard and body cams, as well as bystanders who capture images or videos of crimes, will be able to upload files to the Our Watch database through a phone app.

The database will then sort and organize the files for easy access and recovery. In this way, the app will serve as a permanent, up-to-date database for law enforcement and the public.

“The first thing everyone does when something like this happens is take out their phones,” Obi said. “Our Watch finds a way to bring this footage and that from police officers in a public, accessible space.”

Demand for more transparency

While they have pursued the project for more than a year, their push to develop the application comes with Gov. Pat McCrory’s recent passing of a law that no longer considers police dash cam and body cam footage public record — meaning citizens no longer have the opportunity to access such information through open-record requests.

McCrory told CNN, “One viewpoint of a video doesn’t always tell the whole story.” He added, “The angles can make a difference, and [you’re] not hearing [the sound] often in the video, so that [adds to] the complexity.”

Obi thinks otherwise. For him, more recordings brought to the public means more opportunities to decipher and analyze incidents through a variety of angles.

“Why create the body cameras and record all that footage if nobody can see it?” he said. “For the [Keith Lamont Scott shooting], his wife’s video was taken down by Facebook initially. And then we got 23 seconds worth of dash cam footage — is that really all we get?”

The secure database the students are promoting would make it impossible for videos to be edited or taken down, ensuring full transparency and accuracy. Obi added that it will take more research and cooperation from the law enforcement side to develop an app that serves this purpose while meeting legal guidelines.

Davis, the developer of the app, added that Our Watch would own the videos, creating an added protection and filter between the public and law enforcement through third-party surveillance.

“The reason why we own the public video is so that we can serve as a system for checks and balances as well as a platform for transparency,” he said.

This push for more transparency and public accountability resonates with Davis on a personal level.

After his friend was killed by another civilian in Charlotte, Davis said he was shocked by the lack of information provided by both police and eye witnesses.

“I know for a fact that people had footage on their phones about what happened but they were too scared to come forward,” he said. “My goal is to make sure that people aren’t left with answers like I was.”

Support from law enforcement

Huddled around a computer screen, Obi, Davis and Cliff Parker, chief of police of the Town of Elon Police Department, took a break from their brainstorming session to ask each other a simple, yet prevailing question: “How are you doing since the Charlotte shooting?”Obi, who came to Elon from nearby Mebane, fidgeted in his seat. “It was just too close to home, you know?”

Cliff Parker agreed.

“I know,” he said. “It affects us all.”

To Obi, these relationships — ones fostered by mutual respect and determination — is what drives his project. Given that recent headlines discussing law enforcement officers and young, black men have carried heavy, tragic and conflict-ridden associations, Obi emphasized the value of moving beyond divisions.

“The app focuses on bringing people together to try and make their communities safer instead of creating a division,” he said. “Why not bring everybody to work together? Aren’t we all trying to achieve the same thing?”

Parker, who met with the entrepreneurs to offer advice and contacts, said the idea is innovative and exciting.

“What I find encouraging is that it emphasizes achievement over grievance,” he said. “We’re always better when we’re looking at the solutions, and out of that, we’re working towards the same goal.”

While he noted that continued collaboration would have to take place in order for the app to be viable in legal terms, he emphasized the value of remaining transparent on matters that affect the public.

“The fact that it promotes and fosters a relationship where both the public and law enforcement are held accountable in one secure platform is beneficial,” he said.

Obi added that other law enforcement officers have shown positive responses and the response has transformed from, “What will it look like?” to, “When will we get it?”

Support from the community

While the team of students have been able to release a prototype of the app, they said they lack the funding to officially develop and release it.

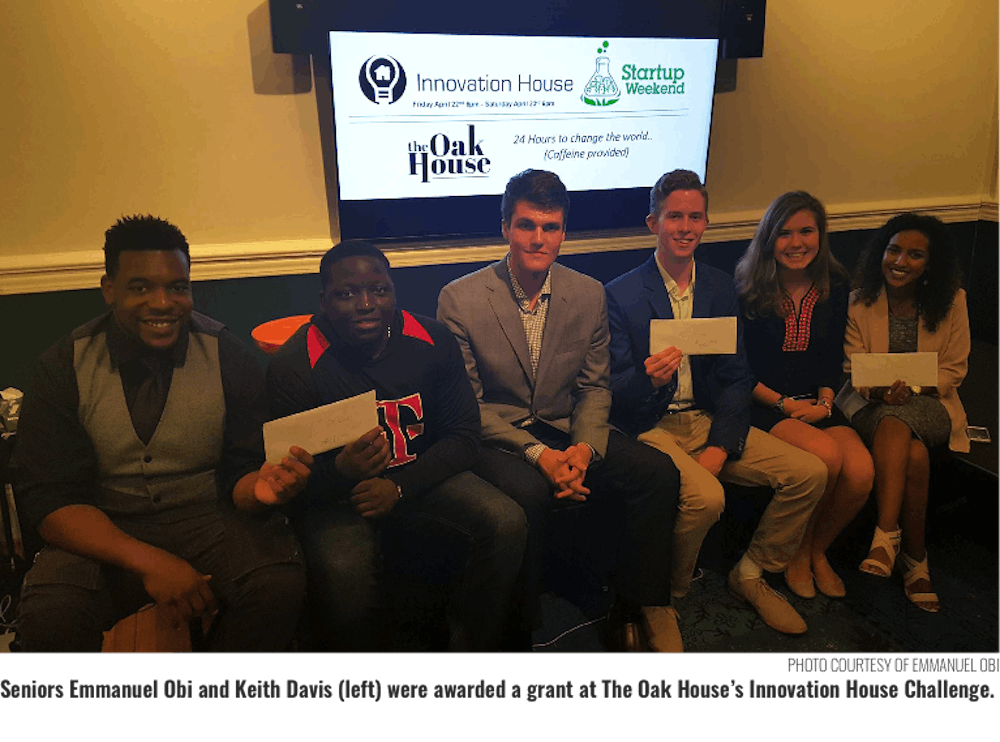

With the exception of a $300 grant awarded to them by Elon’s Maker Hub “KickBox Challenge” and a grant from the 24-Hour Innovation Challenge sponsored by The Oak House, the group said they have received little to no funding from community supporters — making it difficult to release more prototypes.

Senior Matt McCleary, who serves as Our Watch’s financial manager, said community support is vital in turning the app into a reality.

“We launched a Kickstarter page, and at the moment, there’s only $16 in that account,” he said. “It has been difficult working off of a minimal financial base, especially when we see the huge potential this could have on current cases around the nation.”

But the group stressed that they are not discouraged. With positive responses coming from police officers, mentors, strangers and even Ian Baltutis, mayor of Burlington, Obi said they are not thinking of giving up anytime soon.

“Our Watch is the first thing I think about every morning and the last thing I think about before going to bed,” Obi said. “Because we firmly believe in the immense impact it can have in restoring accountability, and because we’ve received feedback from so many people who feel the same way, we’ll continue working to make it a reality.”