A report released earlier today by the Elon University Presidential Task Force on Black Student, Faculty, and Staff Experience highlights the disconcerting emphasis black and non-black survey respondents placed on lack of diversity, inclusiveness and support for black students, faculty and staff at Elon.

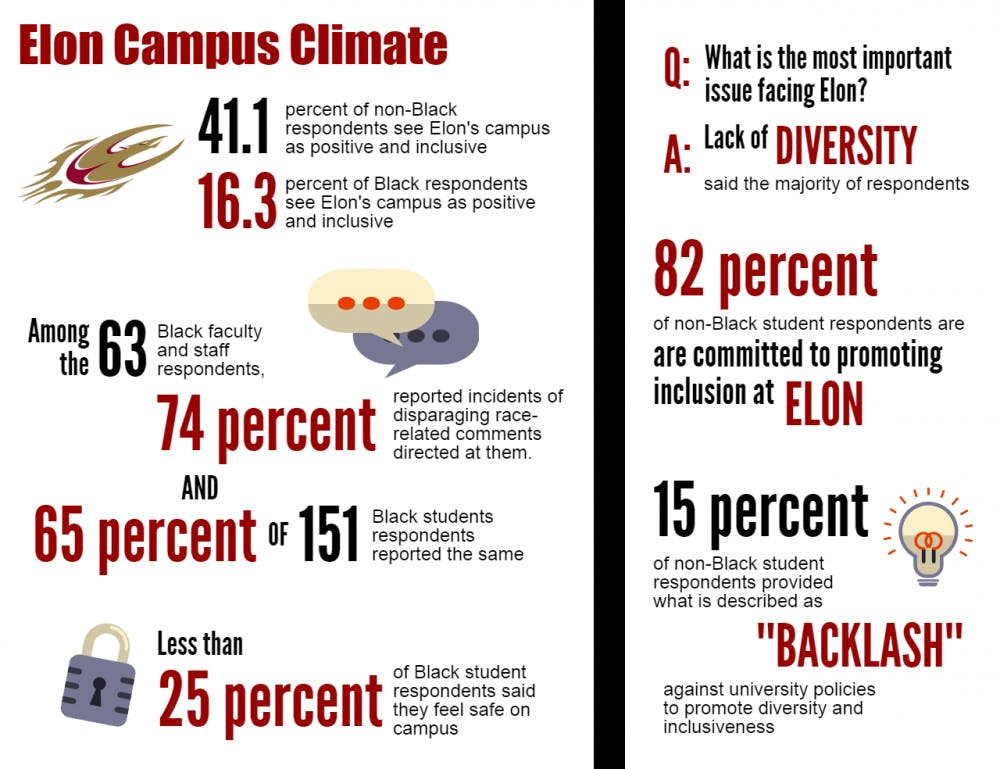

The report, a product of responses from a December 2014 campus climate survey, reveals, among other findings, that “less than a quarter of Black survey respondents said they felt safe on campus.”

Senior Tony Weaver said the issue of safety goes beyond the physical.

“From my perspective, there are times on this campus where I don't feel safe. But it's not only because I'm in fear of physical harm. It's more of a sense of not belonging,” he said. “While it isn't something I experience often anymore, I completely understand how students could feel unsafe.”

Weaver isn’t the only one who can identify with the more than 75 percent of black students who reported feeling unsafe on campus. Freshman Kenneth Brown Jr, who was recently elected class president by the Class of 2019, said he and his friends have encountered this feeling on campus.

“Personally, I haven’t felt unsafe on campus, but safety does come up when I’m talking with friends,” he said. “Me and my friends usually tell each other to stay safe when we’re walking at night.”

Beyond the issue of safety, the report also draws attention to the disparity between black and non-black respondents’ attitudes toward inclusion at Elon, stating that “overall, Black students, faculty, and staff respondents were less positive than non-Blacks.” In particular, 41.1 percent of non-black student respondents rated Elon’s campus as “positive and inclusive,” while only 16.3 percent of black student respondents categorized Elon in the same way.

In the same vein, 73.9 percent of non-black faculty and staff respondents said they feel Elon includes Black identity in its efforts to be an inclusive community, while only 39.4 percent black faculty and staff respondents felt the same way.

The Task Force and its process

Elon’s Presidential Task Force was appointed in November 2013 and charged by President Leo Lambert with making Elon a more supportive environment for black students, faculty and staff.

The development of the Task Force couldn’t have come at a better time. Fall 2014 saw black students constitute the lowest admittance rate of all ethnic groups. The years before and after, Elon became the scene of several racial incidents, including acts of racial bias in 2011, 2013 and 2015 that prompted campus-wide outrage.

As part of its mission, the Task Force emailed a survey on campus climate to students in December 2014. The online survey, comprised of a series of questions on a standard Likert scale as well as areas for free response, sought to collect both quantitative and qualitative data to understand the experiences of black students, faculty and staff at Elon.

According to the report, 11 percent of undergraduate and graduate students and 28 percent of employees fully completed the survey. These respondents included 36 percent of the self-identified black student population and 30 percent of the black-identified employee population.

In spring 2015, a series of focus groups with students, faculty and staff were also held to gain a deeper understanding of information revealed in the surveys. To account for students who did not feel comfortable completing the online survey, task force members also held one-on-one interviews with several students, faculty and staff.

Once the surveys, focus groups and interviews — as well as research into the policies of peer and aspirant institutions — were completed, the Task Force published its findings and subsequent recommendations as “Report of the Elon University Presidential Task Force on Black Student, Faculty, and Staff Experiences Submitted to President Leo M. Lambert.”

Recommendations and reactions

The list of Task Force recommendations spans six printed pages and includes 16 proposals, many featuring multiple parts. Some, such as the suggestion to “host socials that bring together student organizations and groups of different races and ethnicities,” are reiterations of past university efforts to encourage inclusivity.

Others, though, stand out — such as the recommendation to partner with the Elon Core Curriculum “to deepen and promote central components like power, privilege, and oppression related to race and ethnicity in the core curriculum.” In the same section, the report also proposes adding a “diversity offering” for freshmen as a required element of the Elon Core Curriculum.

The university has offered sessions and workshops sponsored by the Anti Defamation League (ADL) before, even offering four-hour A CAMPUS OF DIFFERENCE workshops throughout last year’s Winter Term, according to Elon’s website.

The report acknowledges Elon’s efforts in the area of diversity education, though it went on to state that “community members who may be most in need of education surrounding White privilege are able to opt out of” programming that would be beneficial to them and the community, like workshops or training sessions.

The Task Force recommended addressing these concerns by making certain programming mandatory, and one way to do that, they state, is to incorporate discussions of race and ethnicity into the core curriculum.

Weaver said Elon is making the right decision.

“Elon is a place of higher education. With things like race, privilege and institutions of oppression becoming even larger issues in the United States, as a liberal arts university, it is their responsibility to educate students on it,” he said. “Education is the cure to ignorance.”

Starting the discussion, according to Weaver, is Elon’s obligation. Then, the resulting conversation and education can do the rest of the work.

“In my opinion the best way to strengthen inclusivity would be to remove the taboos around discussing race and make the entire student body engage in the conversation,” he said. “No matter how uncomfortable it makes them.”

Brown couldn’t agree more.

“It's going to get more people talking,” he said. “It's all about process and how to incorporate these ideas, how to keep the conversation going.”

To keep the conversation going, the Task Force advocates for more than just mandatory diversity and inclusivity seminars. In the same section of the report are included recommendations to establish a Living Learning Community dedicated to challenging issues of racism and to host a conference alongside other local universities, including Historically Black Colleges and Universities, to discuss issues of race and racism on predominantly white campuses.

At the end of the day for Weaver, any action on the university's part that brings the topic of race into the open is a smart one.

“Many people don't want to talk about race because it makes them uncomfortable,” he said. “That must change. I think conferences and student seminars are a step in the right direction.”

According to Randy Williams, dean of multicultural affairs, hard copies of the Task Force report are available for students at the Center for Race, Ethnicity & Diversity Education (CREDE) in Moseley 221.