In the desert, they stopped to ask for water. Instead, they got detained.

The 17-year-old Honduran girl and her 10-month-old daughter are two of 68,000 children who have crossed the border into the United States alone, fleeing a region rife with violence.

The young mother and daughter were ushered into a crowded “cooler,” a shelter at the border, where they stayed for 15 days before being transported to a different shelter in Arizona.

“They treated us bad,” the Honduran teenager said. “We slept on the floor, and it was very cold. They kept telling us, ‘Why are we here? This is not our country.’”

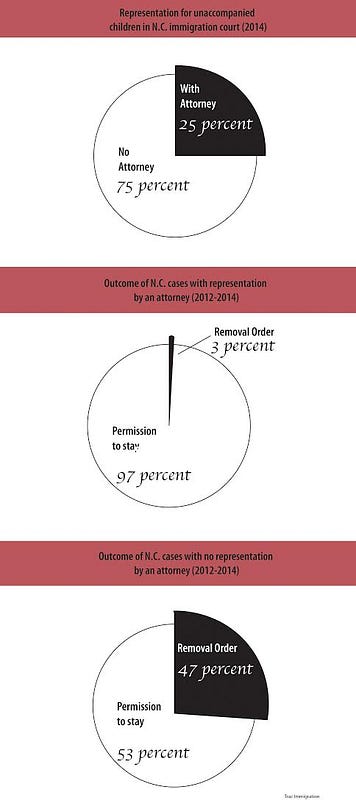

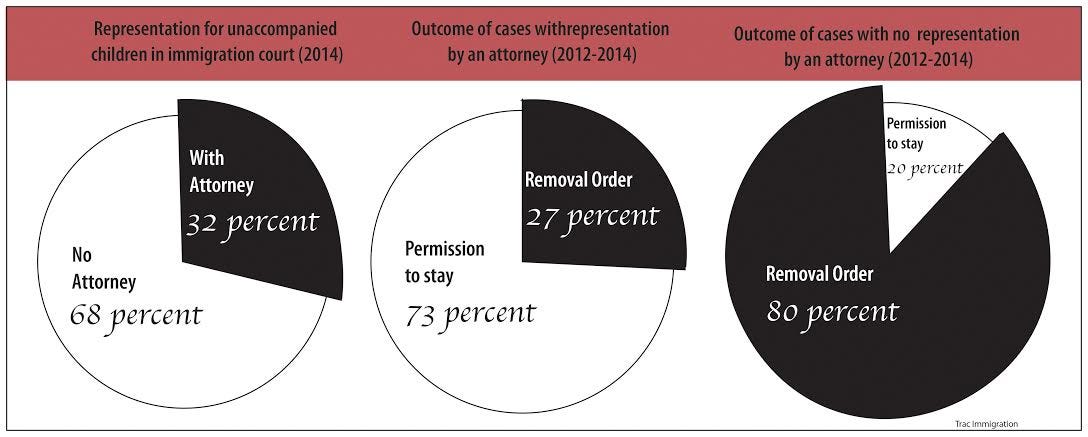

Out of the 2,252 minors in North Carolina, these two are an anomaly in that they received legal counsel when they arrived in the United States. For the remainder who struggle through the system without representation, deportation is often an inevitability.

The pair began their journey in December, when they boarded a bus in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. They drove for days, walked for miles and, a month and a half later, crossed the Rio Grande to reach the Texas border.

Like most unaccompanied minors, they were escaping a neighborhood teeming with gang activity.

“They were assaulting a lot of people,” the mother said. “And sometimes, they killed people. Instead of a robbery, they killed them.”

Nearly 20 days following their detainment, they were reunited with the teenager’s mother, who was granted custody of both unaccompanied minors by a judge in Durham County.

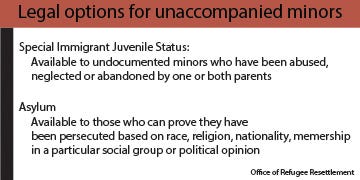

The two children are on track to receive a Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) Status, a form of relief that provides green cards to immigrant minors who have been abandoned by one or more parents. For now, they’re in limbo, awaiting a ruling from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services that will decide if their claim is valid.

Special Immigrant Juvenile Status

Derrick Hensley, a family court attorney who represented the new custodian of the young immigrants in court, said SIJ Status is a viable option for many unaccompanied minors. With the influx of unaccompanied minors in the state, there are more cases than there are attorneys to present them. SIJ cases require a complicated mix of family law and immigration law that few attorneys are willing to undertake.

It’s even more difficult for unaccompanied minors to find legal representation at an affordable rate. Hensley takes on a combination of paid cases and pro bono cases.

“There aren’t immigration attorneys and family attorneys who are willing to take on these cases,” Hensley said. “They fly under the radar, the kids get deported and then, whether they live or die, nobody ever hears from them again.”

In his experience, children with valid claims for SIJ Status have a relatively high chance of receiving a green card. But recently, he’s noticed pushback from Customs and Immigration Services.

“They don’t like that there are so many of these cases now, and they want to find reasons to deny them,” Hensley said. “There’s some level of reviewability, but a lot of it comes down to how the officer was feeling that day, whether they get the Special Immigrant Juvenile visa or you just get a pile of trouble that doesn’t end.”

CIS officers can also reject cases in which they determine the judge does not know enough about the case.

A House of Representatives Judiciary Committee voted March 4 to recommend the passage of a bill that would expedite the deportation of children who crossed the border on their own.

Though this bill would effectively speed up the deportation process, President Barack Obama instructed courts during the surge at the border last summer to rearrange their dockets, ensuring underage immigrants appeared before a judge within 21 days of Immigration and Customs Enforcement filing a case against them.

In the past year, Hensley has represented 22 unaccompanied minors, which he said was up from previous years. Attorneys across the state and nationwide saw an increase in the number of unaccompanied minors in their caseloads in the summer of 2014, when minors began crossing the border alone at unprecedented levels.

Hila Moss, the attorney for the Development, Empowerment, Action, Relief (D.E.A.R.) Foundation?—?a North Carolina immigration advocacy group?—?said her caseload skyrocketed in June, when around 1,200 juveniles had already arrived in the state.

Currently, 75 of Moss’s clients are unaccompanied minors, six of whom have been placed with sponsors in Alamance County. The D.E.A.R. Foundation offers legal counsel at a discounted rate based on what each client can afford and, in some circumstances, pro bono.

Moss said she saw a rapid shift in how juveniles were treated in the court systems over the course of a month. In May, when she represented two juvenile clients in Charlotte, judges opted to keep their cases closed unless the Department of Homeland Security requested they be reopened. A month later, when she had six children on the docket, each of them was denied closure.

“It was very dramatic in how quickly it happened and how quickly it changed their policy,” Moss said. “It went from being very kid-friendly, very kid-oriented, and then with the influx of the unaccompanied minors, they had, all of a sudden, huge targets on their backs.”

And judges don’t always understand the conditions surrounding the cases of unaccompanied minors, she said, noting she spends a significant amount of time educating judges who haven’t researched the cases or aren’t familiar with federal law.

“They don’t know what’s going on, and they don’t care what’s going on, which I think is the worst part,” Moss said. “As far as they see it, that’s not their purview. And I hear that from a lot of other attorneys.”

Courtroom struggles

Martin Rosenbluth, a clinical practitioner in residence for the Humanitarian Immigration Law Clinic at Elon School of Law, said judges have placed the cases of unaccompanied minors at the tops of their dockets in the past year.

“They’ve put their cases on what’s called the ‘rocket docket,’ so they’re moving those cases much more quickly than other removal proceedings in the immigration court,” Rosenbluth said. “So you’ll get deported more quickly if you came as a recent arrival, including if you’re a minor.”

In court proceedings, juvenile immigrants aren’t limited to applying for SIJ Status, though it is the most common route and the easiest way to avoid deportation. If a minor can prove he or she has a fear of future persecution upon returning home based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion, there’s a chance of being granted asylum.

This can be difficult to prove because it requires proof of persecution on specific grounds, and juveniles more often flee to escape violence or because they’ve been abused. In asylum cases, minors must also prove that no place in their home country is safe for return. The fact that gang violence is endemic in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador isn’t enough to warrant an individual grant of asylum in the eyes of the immigration court.

“It’s just like you live in a bad neighborhood,” Rosenbluth said. “Even if you can show that you have a well-founded fear of gang violence or of the types of violence in the community, that just isn’t sufficient to have your request for asylum approved.”

Acquiring Counsel

But achieving SIJ Status or asylum in court is nearly impossible without a lawyer, which is not appointed if a minor cannot afford one, Rosenbluth said, noting an asylum case can cost anywhere from $5,000-$10,000.

The going rate for counsel in a SIJ Status case runs from $2,500-$4,000 for the portion that takes place in family court, with an additional $2,000-$3,000 for immigration proceedings, he said.

“Without an attorney, it’s basically hopeless,” Rosenbluth said. “I don’t think getting Special Immigrant Juvenile Status without an attorney is remotely possible.”

Even with an attorney, there are a lot of hoops to jump through.

Rosenbluth, who formerly practiced immigration law at Alamance Law Office in Alamance County, said he took on three or four new cases for unaccompanied minors each week during the summer of 2014.

Often, he said, attorneys and their underage clients are not given enough notice to plan for the hearings because the dates get changed.

“Let’s just say the procedures are not that organized,” Rosenbluth said. “We’re seeing a lot of cases where these kids or their sponsors just never get notice of the court dates because they just move them so fast.”

This affects the outcome of the case by limiting preparation time and compromising the ability of the minor to make it to Charlotte for the hearing.

Children who appear in court face additional complications. Interpreters help them overcome the language barrier, but a comprehension barrier poses more of an obstacle, particularly if the minor has experienced trauma.

“How do you expect a two-year-old or a four-year-old to answer any of the questions about their case?” Rosenbluth said.

Assisting unaccompanied minors

Nonprofit agencies have been helping unaccompanied minors settle into a new environment in North Carolina.

Lutheran Services Carolinas (LSC), an organization that assists with refugee resettlement in North Carolina, has helped juveniles navigate the legal system by linking them with attorneys who will take their cases pro bono. LSC services also extend outside the courtroom and into the homes of children and their sponsors.

“Obviously, when the children arrive there are usually a lot of problems,” said Mary Ann Johnson, director of community relations for LSC. “We need to make sure we do home studies, much like you would for foster children, to make sure they’re being cared for.”

Johnson said they have assisted 84 unaccompanied minors this year, which is up 68 percent from 2014. She mentioned that the majority of them have been placed with sponsors in Wake County.

Unaccompanied minors, particularly those who have been victims of human trafficking, require additional aid on top of the usual background check performed on sponsors, home evaluations and legal help.

“Most of them are fleeing some kind of violent situation,” she said. “Obviously those children need special attention and counseling.”

The U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI), an advocacy group in Raleigh, provides a similar service, assisting minors and their families in finding affordable legal help.

“A priority for us is that they need legal counsel for their immigration hearing,” said Stacie Blake, director of government and community relations for USCRI. “That’s been an ongoing problem.”

Federal data compiled by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, a research center that compiles federal data under the Freedom of Information Act, shows that 32 percent of unaccompanied children had legal representation in immigration court in 2014. The data also showed that, in 73 percent of cases where a minor was represented by an attorney in the past two years, he or she was allowed to remain in the United States. Of those who weren’t represented, 15 percent were allowed to stay.

“I think anyone can agree it’s ridiculous for children to represent themselves,” Blake said.

Some North Carolina residents are less receptive to welcoming unaccompanied minors into the state, arguing they negatively impact communities.

“They are a direct threat to the well being of our state,” said William Gheen, president of Americans for Legal Immigration. “Many Americans have lost their jobs and lost their homes. Thousands of Americans are losing their lives each year due to the breach of our public.”

Gheen advocated for the minors to be detained at the border and sent back to their home countries.

Trickling into schools

Federal law dictates all children in the United States have a right to public education regardless of citizenship status, and this includes unaccompanied minors, many of whom have been enrolled in North Carolina school systems.

The Obama administration issued a set of guidelines in 2014 outlining the documentation that students must provide to enroll in public schools, reiterating that school districts may not inquire about immigration status.

Because of this, public school officials have no way of tracking if the students are documented. But some have seen a slight increase in the sizes of their English as a Second Language (ESL) programs.

“Whether they’re unaccompanied or not unaccompanied, we don’t keep those statistics,” said Carlos Oliveira, Director of ESL for the Alamance Burlington School System. “Are some of those kids possibly? I guess so.”

The Alamance Burlington School System has not yet implemented new policies or services for this demographic specifically, but administrators have purchased more supplies for all students who enroll midyear.

“Probably last year in March we did see more late arrivals into our intake center,” said Oliveira. “We did see some more students start a little bit later than in past years. We have seen a little bit of an increase in students starting in March and April.”

Sashi Rayasam, director of ESL services for Durham County Schools, said their program has around 300 students total, but she does not know how many of them are unaccompanied minors.

Durham County, with 215, has the third-highest number of unaccompanied minors in the state. She said the district has been working to add the resources this group of students require, including new instructional services and strategic group meetings.

“It’s more than ESL, it is a school system and city,” Rayasam said. “[It takes the] entire Durham to raise these students. We embrace every child that walks through our doors.”

But this doesn’t really matter for the teenage migrant from Honduras, who is in educational limbo because she finished high school back in her home country and could not enroll in Durham.

For now, she’s attending English classes at a church in Durham, awaiting her 18th birthday, when she plans to begin community college.

“The first thing I have to do is learn English,” she said. “And after that I don’t know. It’s hard to study being an immigrant and not knowing English. It’s hard to know what to do.”