Thousands of residents of Alamance County, North Carolina, don’t know where their next meal is coming from. They are a part of the one-in-six Americans who are food insecure.The USDA defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.” But many Americans don’t have this privilege.

According to Feeding America, the overall food insecurity rate in Alamance County was 17.1 in 2012. This figure means that nearly 26,000 people in the county are food insecure.

Mary Crabtree is an Alamance County resident who remembers times when she couldn’t afford to buy balanced meals for her four kids.“There have been times when my kids have had to eat noodles or sandwiches for like a week,” she said.

Crabtree is eligible for SNAP, the government food assistance program that helps low-income families to afford food.

The program helps people to pay for food through an EBT card that is accepted at most grocery stores. More than 12,000 county households received the program's food stamps in 2012.

Earlier this year, North Carolina experienced a backlog on food stamp applications. The federal government threatened to cut funding for the program before the state caught up on giving food assistance to residents.

Crabtree is one of the many working American adults who receives governmental food assistance to help make ends meet. She has two jobs and is a full-time student, going to classes three days a week and taking some online courses. But this spring, she found herself in a tight spot and went to the Salvation Army of Alamance County for additional food.

“At the time, I wasn’t getting food stamps,” Crabtree said. “My tax money was saved up for groceries. And when my tax money was running out, I applied for food stamps. But there was a gap until I started getting them.”

Christi Thomas is the food pantry coordinator at the Salvation Army of Alamance County. The organization provides emergency food boxes to people in need who bring a paycheck and valid ID.

“Food stamps have been cut in the past few months, so people haven’t been getting what they’ve gotten before,” Thomas said. “Also different things may come up, and they may not have [money]. Like their power may have gotten turned off and they may have lost everything in their refrigerator or had a fire and lost everything period. Those types of situations are common for us.”

But some residents’ incomes make them ineligible for government food assistance, and they still struggle to find their next meals. Food pantries across the county offer items to help close the gap.

“If your car breaks down and that’s an extra expense that month, you may not have enough money for groceries,” Thomas said. “You may just need enough to get you through until you get paid again, and that’s what we’re here for.”

But the task of feeding Alamance County residents isn’t easy. Feeding America estimated that over $12 million is needed for these efforts in the county.

And added pressure came last year when Loaves and Fishes Christian Food Ministry, the largest food pantry in Alamance County, closed. This put other food pantries in a crunch, as many of them scrambled to expand their offerings.

The Salvation Army of Alamance County and other organizations extended their services. Thomas said more people started to come for food assistance.

“It’s no one particular race. It’s no one particular age,” Thomas said. “Everyone is hurting. People who have never needed to come for assistance before are having to come now.”

In North Carolina, children have a higher food insecurity rate than adults. And in Alamance County, more than 1 in 4 children are food insecure, according to Feeding America.

|

The U.S. government’s National School Lunch Program provides low-cost or free meals to more than 31 million children in the nation's schools each day. According to Alamance County’s 2013 health report, 55.6 percent of county students were eligible for free and reduced lunch in 2011, an increase from 52.2 percent the year before. But children who receive these services sometimes have trouble finding reliable meals during weekends. That’s why people in the county have started programs that allow students to discreetly carry home meals for their families in backpacks. Kit Shields, who started the Backpack Ministry at People’s Memorial Christian Church in Burlington, said the church’s program serves between 35 and 40 children each school year. “It takes awhile to figure out who is in need because they're not children who are necessarily on free lunch,” she said. |

|

But during the summer, kids don’t receive meals at school, putting parents in a bind.

“Most girls don’t eat as much as boys,” Crabtree said. “My daughter eats as much as boys do. When they’re home in the summertime, they’re like garbage disposals.”

This time of the year is also when food pantry shelves start to run low after exhausting holiday season donations, according to Thomas.

“Spring and summer are the times when we truly do need [food] the most just because there are so many people who have children who are normally getting fed in school,” she said.

Food insecurity is closely linked to poverty. And according to U.S. Census Bureau data from 2008-2012, 17.3 percent of Alamance County residents fell below the poverty level, compared with 16.8 percent of residents in North Carolina.

Food insecurity can lead families to turn to food options that are inexpensive but unhealthy, such as fast food.

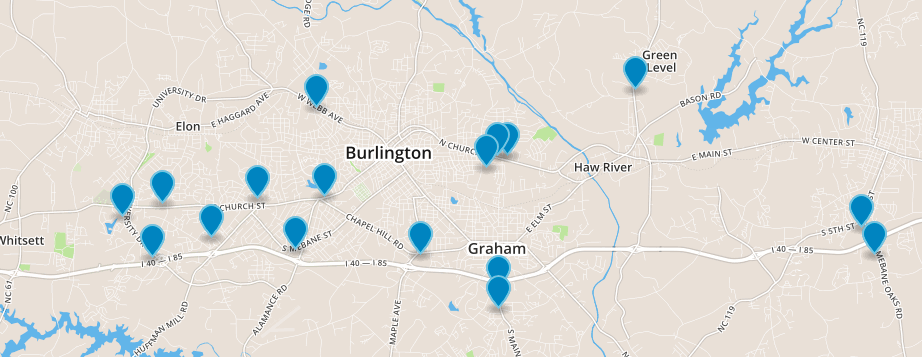

Also, for some Alamance County residents without transportation, it’s difficult to find fresh fruits and vegetables. According to survey data, 43 percent of residents don’t have access to fresh produce within one mile or walking distance from their homes. This map is a link that shows the major grocery stores in the county.

Many food pantries follow government guidelines for nutrition. The Salvation Army of Alamance County allows families to come once a week to receive fresh fruits, vegetables and bread donated from Target and Lowes Foods stores.

Crabtree said she tries to make balanced meals every day but that it’s sometimes difficult to eat well on a budget.

“It’s more expensive to eat healthy,” she said. “I will buy a bag of apples for like $6 and they’re gone in two days. And they’re a snack, not a meal. It’s very hard to keep healthy items in the house.”

When Crabtree struggles to find money for food and other expenses, she said she relies in her faith and looks toward the future.

“There are challenges every day,” she said. “Some days, I only get two hours of sleep. I chose to have four kids. Going to school is only going to better our lives in the future.”