I will miss meandering through the open, European-esque plazas of Old Quito. I will miss the walks through the dozens of parks teeming with joggers, dogs, futbol players and the occasional couple. I will miss the sound of Spanish rattled off at lightning speed, the friendliness of Quito’s people, the food and the stunning scenery that surrounded me at every turn.

All things considered, it was both an enjoyable and successful ten days in Quito, Ecuador, documenting the education system in the South American country for a fellowship from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.

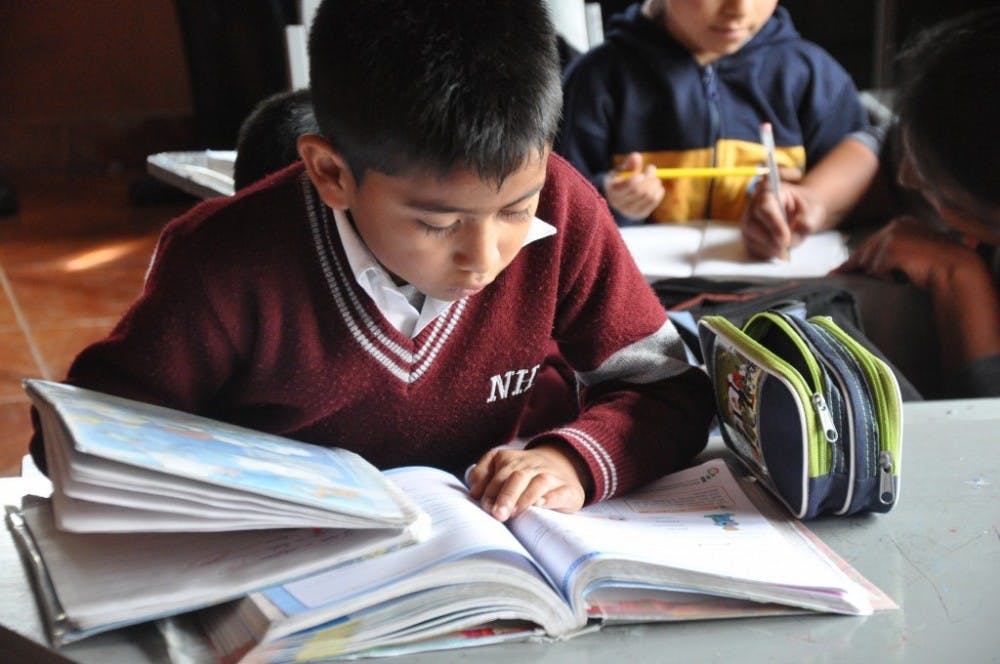

While in Ecuador, my partner and I spent three days alongside members from the iMedia program interacting with and interviewing students (the children were the cutest), teachers and alumni from the Escuela Nuevos Horizontes del Sur, a tiny, rural private school a winding and mountainous 45-minute drive outside Quito.

We also spoke with professionals involved in the higher education system in Ecuador, including a member of the university accreditation board, the head of a language immersion program for both exchange students and native Ecuadorians and an American professor who helped revamp the teacher training programs in dozens of schools across Ecuador and other nations.

The interviews helped shape the narrative of a nation that for many years, and even still to this day, lacked quality education for its citizens, but now is trying to turn the tide to provide a better life for its people.

Once upon a time, children in rural areas who spoke an indigenous language struggled to succeed in a Spanish-speaking school system. Now with compulsory education mandated by the nation’s constitution and about 5 percent of the GDP spent on education–compared to the United States’s 5.4 percent–students are learning, and some are even going on to receive degrees in higher education.

But even with these improvements, the Ecquadorian education system is vastly different from America’s and I came away from the trip with a greater appreciation for our system, despite its many flaws.

Here, choice and opportunities abound. It would be very difficult to get funding by an Ecuadorian university to complete the type of trip from which I just returned. And with new changes in Ecuador’s constitution and university accreditation process came a new entrance exam that determines a student’s field of study for him or her. Emphasis on technical skills and science-related subjects leaves the chance to earn a liberal arts education similar to Elon and other U.S. universities slim to none.

While the two systems are so different, the one thing both countries share is the passion of teachers trying to make a difference in a student’s life. Education is clearly important to a successful future, and from listening to the principal and teachers of Escuela Nuevos Horizontes del Sur, who all teach multiple subjects to both primary and high school students, I could sense the intense desire for making their students feel special and encouraging them to reach for their dreams.

Going to Quito was a great learning experience, and I came away from the trip with a greater appreciation for my education and the opportunities I’ve been afforded during my time at Elon. I’m also hopeful for Ecuador’s future and the students seeking knowledge and a better education.